Main content

Reflections from a top negotiator of the recently concluded Pandemic Agreement

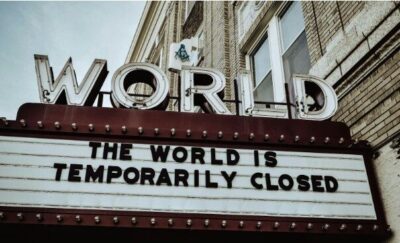

Nearly 300 million confirmed Covid-19 cases – and counting –, over 5.3 million fatalities [1], lockdowns that affected livelihoods and overwhelmed health systems, isolation, loneliness, economic turmoil, and social unrest. It’s little wonder that, in December 2021, all 194 WHO member states unanimously agreed on the need for a Pandemic Agreement – only the second legally binding health accord in UN history [2]. Never again should the world face such devastation due to a largely preventable disease outbreak.

The first step was setting up the Bureau to facilitate, steer and manage the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB): a member-state-led process “to draft and negotiate a convention, agreement or other international instrument under the Constitution of the World Health Organization to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response”.[3] The Bureau included six members, one from each WHO region[4], and was led by two co-chairs: Precious Matsoso from South-Africa and (until July 2024) Roland Driece, the Director of International Affairs of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS).

We spoke with Roland on a sunny September afternoon in his bright, glass-walled office, watched over by two large posters promoting the Dutch Global Health Strategy and the Dutch Global Health Hub.

So how did that happen: a Dutchman, you, in this pivotal position?

“There was a strong political candidate for the EURO co-chair position, but he eventually withdrew. I had been part of the EU Joint Negotiation Team for the procurement of the COVID-19 vaccines andstrongly involved in the EU-COVID response. So, I thought: why not me? I spoke to colleagues at VWS and contacts in the EU and everyone was supportive. One thing led to another. That’s really all there is to it. And although this was not a political decision, it helped that the Dutch ministers at the time were in favour too.”

And then the INB started. What can you tell us about that process?

“The goal was to have the text for a Pandemic Agreement ready for approval at the 2024 World Health Assembly – just two and a half years later. We began by compiling a longlist of issues to be discussed, based on input from member states. These were grouped into four categories: prevention, surveillance, response, and funding. We then addressed all these over 13 sessions.”

Sounds like a daunting task. What were your expectations and what setbacks did you encounter?

“What really disappointed me was how quickly the sense of urgency faded once COVID measures started to be lifted. Imagine: our first meeting had to be online due to travel restrictions – which obviously didn’t work. Then only the Bureau could meet in person, with others joining virtually. Eventually, we all met face-to-face, wearing masks. And the closer we got to normal conditions, the faster political commitment declined and media attention waned. You can say a thousand times that we should fix the roof whilst the sun is shining, but apparently it doesn’t work like that.”

How did you deal with that?

“Luckily, the six Bureau members were all deeply committed. We also had a bit of a ‘we’ll prove them wrong’ mindset. Coming from different parts of the world, content-related differences could easily arise, but as Bureau members we found each other in the procedural approach. And anyway, most of the time we were too busy managing the process and resolving disputes. For instance, African countries were hesitant to invest heavily in prevention. Their stance was: ‘Just make sure we get the vaccines and the funding.’ Others pushed to include specific language on women, LGBTQI+ communities and other marginalized groups, while we preferred the neutral term ‘people’ to avoid politicizing and complicating the negotiations. Then there were geo-political sensitivities relating to countries subject to trade restrictions and coercive measures, such as Russia and Iran. They argued that if you want to fight a pandemic, you shouldn’t exclude countries from receiving vaccines. For others this was a no-go area. It took real effort to align all these differing opinions in one direction.”

There has been criticism that the process was not inclusive and representative enough. What’s your take?

“You’ll always get criticism when you don’t do what parties want you to do. Precious Matsoso and I made it clear from the start: the Bureau is neutral. That has led to both of us being criticized from our respective regions. Member States are quick to speak up when they feel their interests are not represented strongly enough, especially when money is involved. One of our EU friends even complained to minister Kuipers that I wasn’t defending the interests of the pharmaceutical industry enough. Thankfully, Kuipers wasn’t impressed.

“And there were other controversies to navigate. You remember how strongly some groups in society agitated against the pandemic measures and how anti-establishment they became. That ridiculous negative context was really draining. If it wasn’t so serious, you could call it fascinating. We even found out that in 20 different countries identical questions were raised in parliament. Clearly, there was a well-coordinated international anti-lobby in play. It’s sad that the world came to this.

“I have received hate mail myself – letters sent to my home, with drawings of gallows and such. We had already seen extreme threats aimed at political leaders in COVID-times, but I was surprised that this would happen at my level, too.”

Speaking of which, the political situation in the Netherlands wasn’t exactly helpful for your role, was it? A motion was adopted in Parliament in April 2024 to ask the WHA to delay the voting on the Pandemic Agreement. And on July 2nd, 2024, the Schoof government took office. Not exactly happy times for multilateralism….

“Complicated political times indeed”, says Driece. He and his team tried to explain to their political bosses that the Agreement served both global and national interests — but without success. Driece decided to step down as co-chair. “My position had become untenable. I could not do this job without backing from my own government.” During the WHA in May 2025, when the Pandemic Agreement text was adopted with a year’s delay, the Netherlands chose to ‘take note’ of the text and abstain from the vote.

The United States was absent at the last WHA. What does their withdrawal from the WHO mean for the Pandemic Agreement and its implementation?

“Most of the negotiations took place under Biden’s administration. They weren’t too thrilled but had no intention of sabotaging the process. The situation is very different now. And the real work still needs to be done, starting with the Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing system, due next year – a tough task given the diminishing political commitment. How to accomplish this without the close involvement of the American CDC is a serious concern.”

How do you look back on your experience in this role? Would you do it again?

“Yes. It’s a unique process. Of course, there are long and exhausting days of constant talking and little progress. But you try to do something good for the world. Alongside my EU work on the COVID-19 vaccines, this was something I truly believed in and where I could make a difference.

“But if you look at the end result, you can ask yourself: is this really it? Earlier drafts were much more ambitious. I think everyone is disappointed in a way. African countries will ask themselves if they’re helped with this text. The European Commission worries about its impact on their industries. And so on.

“Still, what’s the alternative? It’s better than having nothing. Despite the challenges, it’s worth the effort because this agreement lays a foundation for future work. Global politics are complex now, but who knows what the world will look like in five or ten years? We may be living in a completely different reality then. It’s all possible. Today is just one day.”

References

- https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—21-december-2021.

- The first being the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC; 2003)

- https://inb.who.int/

- Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific

- Motie Keijzer

Text box on PA and PABS

More on Pandemic Agreement and PABS

The Pandemic Agreement is the second legally binding UN health accord, adopted by WHO Member States on 20 May 2025, and designed to strengthen the global response to pandemics. It emphasises prevention, preparedness, equity in access to counter-measures (vaccines, diagnostics, therapeutics), One-Health approaches, pathogen access and benefit-sharing (PABS) and global financing coordination mechanisms. It has a structural, systemic, long-term, equity agenda and complements the already existing International Health Regulations (IHR), which are more about acute-event response (notification, surveillance, travel and trade measures, outbreak containment). So, while the IHR remain crucial for the day-to-day, acute side of pandemic response and are more technical in nature, the PA is in essence a political instrument. This, of course, has complicated its negotiations, resulting in a stalemate on the Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing (PABS) system, meant to be a cornerstone of the PA. The PA was adopted nonetheless, with provisions to negotiate the PABS system by an Intergovernmental Working Group, due to finalize its work and report its findings by the next World Health Assembly in May 2026.

The PABS system aims to establish mechanisms for the “rapid, systematic and timely” sharing of “pathogens with pandemic potential and the genomic sequence of such pathogens” for R&D purposes, and for fair and equitable sharing of the “benefits arising from [such] access”, such as vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics. A first draft was discussed with WHO Member States during the first week of November, with members of the Group of Equity raising concerns about – inter alia – local production, transfer of knowledge and technology, non-exclusive licensing, and a lack of enforceability of the PABS in its draft form [1]. The role of the pharmaceutical industry (as private sector parties not legally bound by an agreement between WHO Member States) in this complex interplay is of course subject to intense debate.

1. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/countries-deem-pathogen-sharing-draft-agreement-inadequate-at-start-of-text-based-talks/