Main content

An account from within

HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Malawi

Although Malawi has made great strides in HIV/AIDS prevention and care in recent years, it remains a country with one of the highest HIV burdens in the world, with one million Malawians living with HIV – representing a prevalence of around 5%. A number which is more than double in the Mangochi district. With 55% of Malawi’s healthcare budget funded by donors, the country is heavily dependent on foreign aid. USAID is the largest contributor, accounting for 13% of the healthcare budget, equivalent to $350 million. Similar as in the rest of the country, a large part of HIV prevention and care in Mangochi is funded by USAID and PEPFAR.

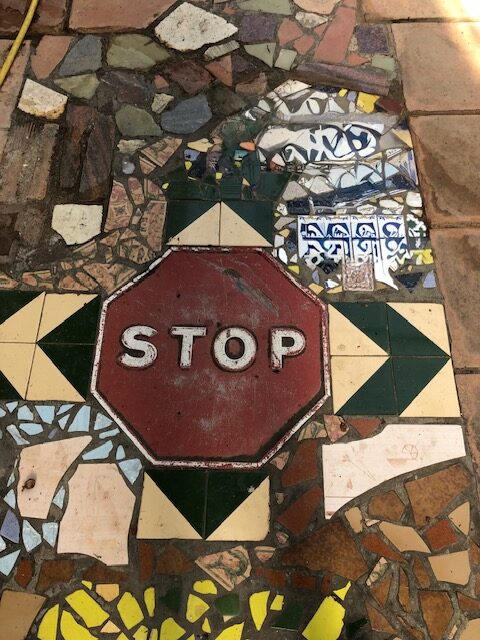

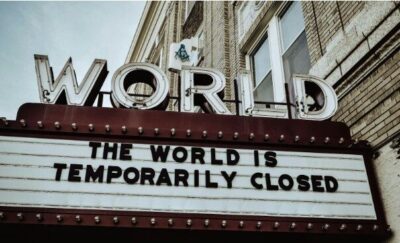

The stop-work order

On January 20th 2025 a shockwave rippled through the global health community as President Trump issued a 90 days stop-work order for USAID, followed by the halting of PEPFAR (the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) a few days later. The suspension of funds resulted in significant disruptions across all USAID-funded health care programmes worldwide, with particularly severe effects on HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Malawi, where approximately 37 % of all U.S. disbursements in 2023 were allocated to HIV/AIDS programmes. Humanitarian groups and UN agencies forecasted immediate and severe consequences, including interruptions to essential health and development services globally.

The day after the stop-work order was issued, its effects were immediately visible at the hospital site. Frontline staff employed by a USAID-funded NGO – officially contracted to provide technical support to the hospital -in reality provided human resources, up to 80% of the staff involved in HIV testing and ART distribution – were instructed to stop working. Testing sites and offices were closed, children and pregnant women in the wards were no longer being tested for HIV.

The effects on people and systems

In the first two months after the funds were suspended, we saw a sharp drop in the number of HIV tests being conducted at MDH. This however did not influence the number of HIV-positive cases – not among the total number of patients, nor among children or pregnant women. The drop in testing could be attributed to absence of the implementing partner in the first two weeks after the cease. The fact that the number of HIV-positive cases did not decline – which would be in line with the drop in testing – was explained that either positive cases were missed in the first two months or, however this was considered less likely, that patients with high-risk behavior still went for testing.

A decline in ART collection was observed across all categories in the months following the stop-work order, with the exception of the final month for male children. In this case a decline in uptake was also attributed to the absence of the implementing partner, as they were the first entry point for treatment and follow-up. In the absence of services some of the children were transferred to facilities closer to their home to prevent drop-out.

The Malawian government responded to the situation with the introduction of a framework in which hospital staff would supervise staff from the Ministry of Health (MoH) performing the test. This did not immediately lead to increased testing, mainly because of shortages of trained personnel to supervise.

Meanwhile I had the chance to interview my colleagues, NGO staff, management of the hospital and MoH frontline staff. Across the board, health workers felt distressed and saw how it affected the team morale, and ultimately their ability to perform. In particular the abruptness of the order and ambiguity of the situation affected those working with the NGO, as they were uncertain whether they would be able to keep their job. The emotional toll experienced by all participants was largely attributed to a lack of clear and consistent communication. This uncertainty not only compromised the mental well-being of healthcare workers but also negatively influenced their attitudes toward their roles, ultimately undermining their sense of ownership over the HIV/AIDS services they delivered. Staff from the MoH staff felt placed into a crisis they had not initiated, yet were expected to resolve without clear guidance.

The situation was not particular at our hospital, as in all areas of the district there was a shortage of frontline workers adequately trained in a newly mandated HIV-testing procedure. A number of barriers were identified in this regard. Firstly, an overall limited number of MoH staff were trained in this Three Testing Algorithm and in digital documentation; and also, those that were trained were not certified as HTC providers because they were not actively engaged in HIV service delivery. Secondly, the allocation of training was centralised (at national level), and often bypassed district level staff. This resulted in a situation in which the entire district lacked certified HTC personnel to fill the gap that was left at the hospital.

The abrupt halt of the stop-work order affected the partnership between the MOH and the implementing partner in many ways. Though the implementing partner resumed work partially after more than two weeks and fully after two months, their staff remained uncertain about how to re-engage and collaborate effectively. Confusion reigned on many levels: regarding the financial survival of NGOs, but also on the day-to-day operations because of lacking guidance from USAID, as well as because of their newly introduced reporting requirements. This uncertainty highly affected the relationship between the NGO and the MOH, as reflected in the words of one of hospital board members:

“They (implementing partner) have been renewing their contract on a monthly basis which is a bit scary. You can’t subject people to that. They are reliable but one leg is inside and one leg is outside but anything can happen. Initially the contract was cancelled, so it may be cancelled any time, so one leg is with us and the other leg is somewhere else.”

The MOH largely depended on the implementing partner to provide quality HIV prevention and care services, a position which makes the Ministry vulnerable in more than one sense. Because of the conditional nature of the funding the donor not only determines what will be funded, but often target their capacity-building efforts solely on their own organisations or programmes:

“What happened is that they (implementing partner) paid for the training but also only trained their staff.” (MoH frontline staff)

The conditional nature of the funding also meant that, when the stop-work order was issued, there was no opportunity for a proper handover of documents, knowledge, or resources, as the donor was unwilling to incur any further costs. This created additional work for the MOH staff, as they lacked clarity on the location and status of essential assets, information and infrastructure.

Looking forward

During the period of my internship which coincided with the stop-order from the side of the US Administration, I witnessed the initial effects of this policy change on the actual lives of patients, and health workers in a district hospital in Malawi. The observations and discussions with my colleagues make me realise the challenges that remain, even though services were resumed after some time. I saw what the volatility from the side of the donors causes, and what being dependent on external funds for essential HIV services and treatment in practice means. The implementing partner is likely to continue their work until April 2026, this date however has already changed sometimes so remains uncertain. This period may help the hospital to address health workforce shortages, and may allow the MOH to train additional and much needed HTC providers.

Promising is the Implementing Partner Framework, the framework that was introduced by the Malawi government, which is a commendable step towards reducing donor dependency and addressing long-standing power imbalances in health staffing. Expecting that these changes will take place overnight is unrealistic. What is needed is a phased transition that will allow implementing partners to gradually move into supervisory role, enabling hospitals to build capacity. Such a gradual model may be applied at Mangochi District Hospital, providing them the space to strengthen its own HIV department while preserving the technical expertise that remains essential for sustained quality of care.

Participants in the research came with a number of suggestions to address the long-standing human resource shortages which may be worthwhile to investigate, including task expansion of supporting staff (e.g., cleaners, drivers), or introducing single-assignment scheduling for HIV department staff. Although task expansion and single-assignment scheduling may appear contradictory, they complement each other: supporting staff gain HTC skills to step in when needed, while HIV providers receive dedicated time to focus exclusively on HIV care. This approach ensures continuity of care, fosters ownership among HTC providers, and may improve retention, particularly when staff are allocated in a decentralized manner. Encouragingly, the MOH had already begun training additional HTC providers and adopted a bottom-up approach in which staff at MDH were first consulted about their interest in training, a strategy likely to enhance motivation and commitment.

Jelle Nederstigt, MD Global Health

* The research report ‘When Aid Stops: A Situational-Analysis of Maternal and Pediatric HIV Care at Mangochi District Hospital Post-USAID’ is accessible through the author.