Main content

Corneal ulceration as a result of untreated traumatic corneal abrasion is one of the leading causes of ocular morbidity and blindness worldwide.[1] In developing countries the main cause of corneal ulcer is a minor agricultural injury sustained during farming, e.g. during plantation and harvest. Patients usually prefer treatment nearby (such as by unlicensed pharmacies, traditional healers, private doctors, or apply eye-drops, already used by others). They therefore present late at the hospital with severe bacterial or fungal ulcers, that are resistant to treatment. The widespread availability of steroid-containing eye drops, contra-indicated in case of simple corneal abrasion, results in an even higher incidence of corneal ulcer.

A community-based strategy for early treatment of corneal abrasions and prevention of corneal ulceration was tested before in several studies. [2-5] It showed that post-traumatic corneal ulceration can be prevented by simple topical application of 1% chloramphenicol eye ointment (e.o.) shortly after the injury, by trained village health workers (VHWs). Immediate treatment with antibiotic e.o. also prevents the development of fungal corneal ulcers, that are otherwise very hard to treat.

Corneal scarring unrelated to trachoma was identified as the second main cause of bilateral blindness in a Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) in Cambodia in 2007. [6] In a hospital-based study (2005) at the CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital (CTEH) 130 patients had been admitted within a period of only 6 months because of a severe corneal ulcer: 50 % was due to trauma, 75 out of 99 eyes were blind (VA <3/60) due to late presentation and 23% of the eyes had to be removed, due to very severe intra-ocular inflammation, resistant to treatment. [7] The high number of patients with advanced corneal ulcers at CTEH was the main reason to initiate a community-based prevention programme, based on the previous studies. The objective was to demonstrate the feasibility beyond a strict research setup and to integrate community-based prevention in a busy secondary eye hospital in rural Cambodia.

Methodology

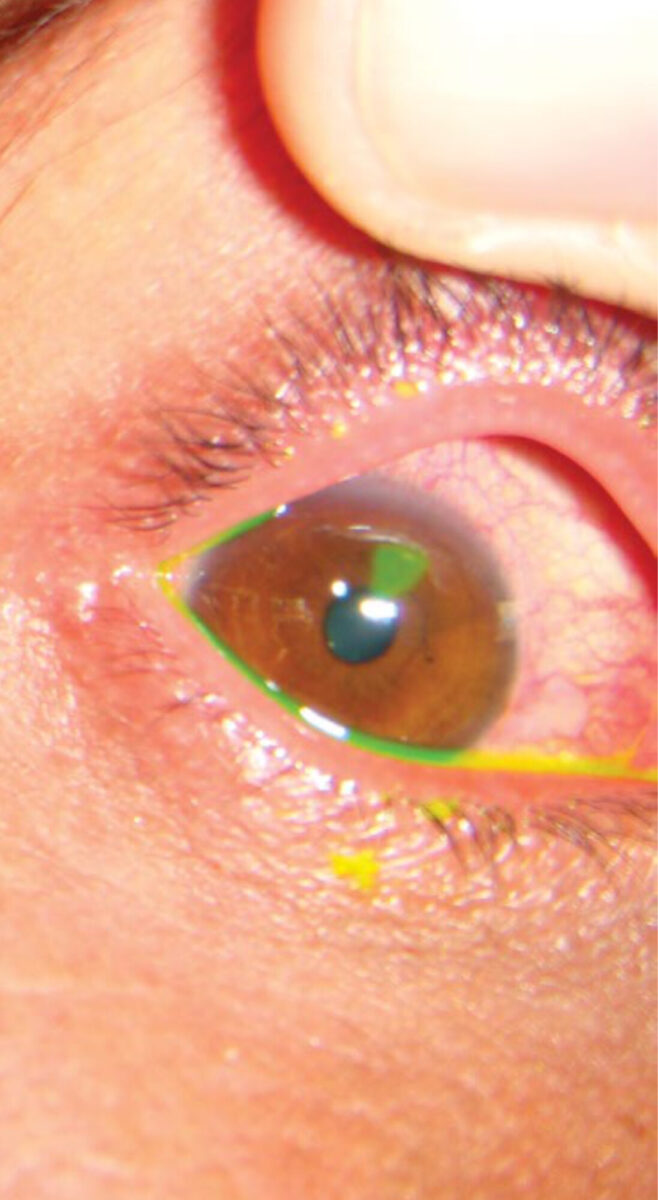

In 2008, 26 volunteer village health workers (VHWs) from 2 communes were trained by staff of CTEH for one week in basic eye care, to identify corneal abrasion with fluorescein strips and a blue torch, and to treat abrasions with 1% chloramphenicol e.o. three times daily for three days. A population of 20,012 in 26 villages was prospectively monitored by the VHWs for 13 months. The villages were located near CTEH in a rural area, dominated by agriculture. VHWs were also taught to record visual acuity (VA) using an E-chart, identifying corneal ulcer and other common eye diseases, and how to refer to CTEH. They were advised to treat a) only residents of their intervention area, b) patients presenting within 48 hours of the injury with confirmed corneal abrasions and c) patients aged 5 years and older. Every month the VHWs were called to CTEH for reporting and follow-up.

Results

During 13 months, 1,147 individuals (female 56.9%, male 43.1%) reported to the VHWs. 783 (78.2%) were farmers. VHWs diagnosed corneal abrasion in 1,004 cases (87.5%). The main results of these 1,004 cases are presented in table 1.

| Corneal abrasion | 1,004 | 100% |

| Healed corneal abrasions | 949 | 94.5% |

| Referred because of corneal ulcer despite treatment | 34 | 3.3% |

| Dropped out | 14 | 1.4% |

| Missing results | 7 | 0.7% |

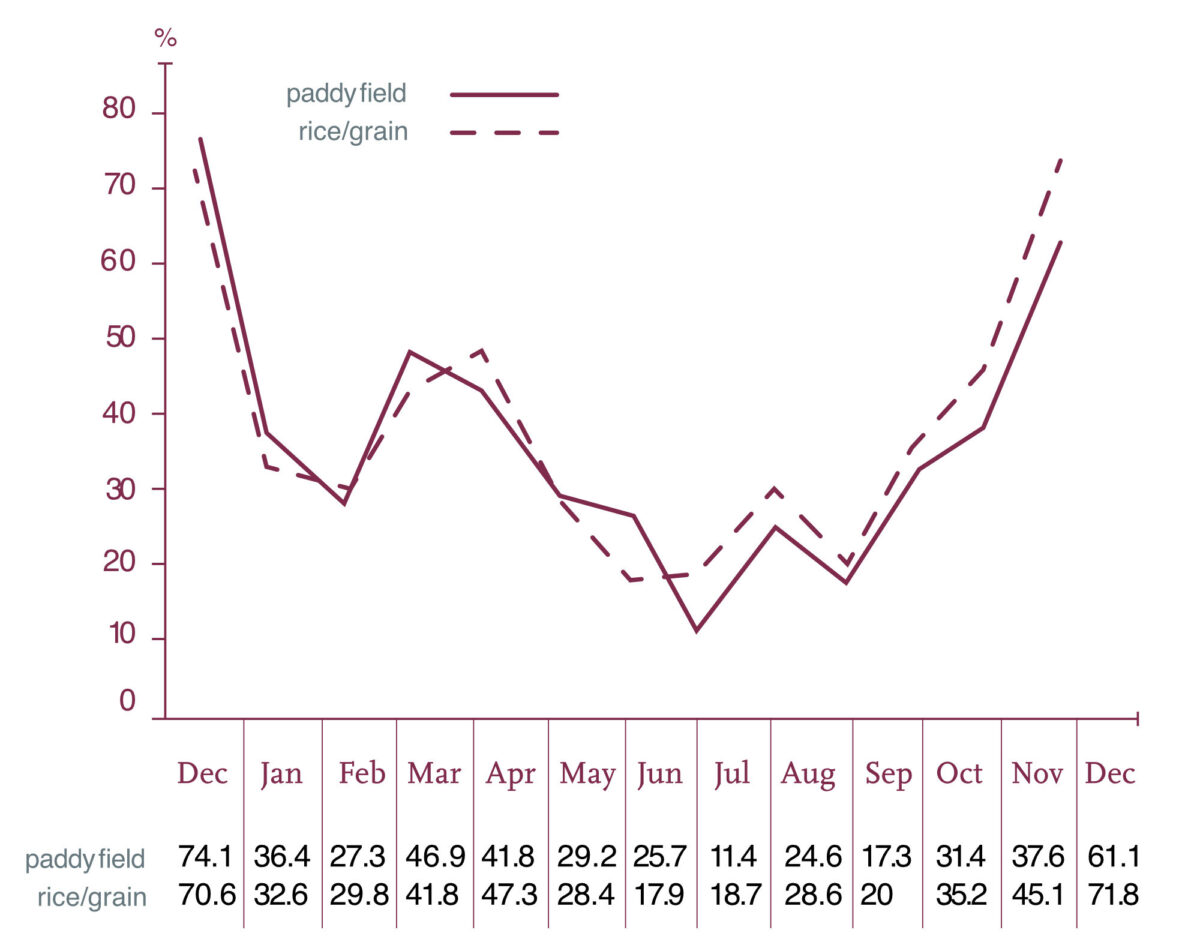

In total 713 (71.3%) patients reported an injury of organic nature, of whom 392 (39.2%) had an injury with rice. Table 2 demonstrates the seasonal correlation between location and agent of ocular injuries. In December 2008 and 2009 (main harvest season in Cambodia), around 70% of all ocular traumas were reported to have happened during work in the paddy fields, with rice grains as major agent. A second peak with a similar pattern could be observed in April and May (minor harvest and early plantation season).

Visual acuity was less than 6/60 in 26.4% of all patients before treatment. After treatment, only 1.1% could see less than 6/60.

Of the 34 patients referred because of corneal ulcer, 9 (26.5%) were lost to follow-up. Of the remaining 25 patients, 7 (28%) corneal ulcers could be confirmed at CTEH. None of these eyes had to be removed. In 18 patients (72%) corneal ulcer could not be confirmed. Additionally, 46 sight threatening (cataract, pterygium etc.) and 28 conjunctivitis cases were referred by the VHWs.

Discussion

This intervention project aimed to prevent traumatic corneal ulcer in a region dominated by agriculture, with a hot and humid climate and known high prevalence of corneal blindness. [6,7] Hospital-based data indicate that at CTEH the overall number of patients that had to be treated because of corneal ulcer decreased from 745 in 2007 to 442 in 2013, a decrease of 41% while yearly more patients attended! This study therefore shows that early application of chloramphenicol e.o. probably prevented a considerable number of corneal ulcers.

Only 28% of the patients referred with corneal ulcer could be confirmed. As the VHWs had been trained only for one week, such misdiagnoses had been expected. There was confusion with a variety of other causes of red eyes -not ulcers- but yet in need of treatment. We consider this therefore as a positive outcome.

VHWs had to be selected from the communes in collaboration with the local authorities. Therefore, this Cambodian experience may reflect the ground reality and may serve as a feasible model of intervention despite some limitations.

The strong correlation between the harvest season, location of ocular trauma and reported agent is important: massive awareness campaigns before the harvest season and basic training of primary health care workers for a short period may be able to prevent many corneal ulcers in communities with a large agricultural sector and hot and humid climates. As a result of our study, we have indeed initiated mass radio messages at the start of the harvest season in order to create awareness of the importance of early treatment after sustained corneal injury.

Continuation by local government

Advocacy efforts by CTEH resulted in significant support by the local government institutions, especially the Provincial Health Department (PHD) of Takeo Province. The project continued during 2010 and 2011 with support from CTEH and was handed over to the PHD in February 2012. In these 3 years, all together 1,985 patients with corneal abrasions were identified (healing rate 98.9%). 24 Patients with suspected corneal ulcer and 246 patients with other eye diseases, like cataract, pterygium etc., were referred to CTEH. We hope that the Cambodian Ministry of Health, will adapt community prevention of corneal ulceration as a national strategy in the next multi-year plan.

References

- Whitcher JP et al. Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:214-21.

- Upadhyay MP et al. The Bhaktapur eye study: ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:388-92.

- Maung N et al. Corneal ulceration in South East Asia II: A strategy for the prevention of fungal keratitis at the village level in Burma. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:968-70.

- Getshen K et al. Corneal ulceration in South East Asia I: A model for the prevention of bacterial ulcers at the village level in rural Bhutan. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:276-8.

- Srinivasan M et al. Corneal ulceration in South-East Asia III: prevention of fungal keratitis at the village level in south India using topical antibiotics. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:1472-5.

- Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness (RAAB). National Program for Eye Health, Ministry of Health Cambodia, 2007.

- Hall T, Lion F. Corneal ulcer in a Cambodian eye hospital. Community Eye Health Journal 2005; vol 18,no.53:81.