Main content

When the wind blows strong you bow and when she is quiet again you bounce back

Many mental health workers think their ability to treat asylum seekers and refugees is limited. They are often overwhelmed with feelings of powerlessness when they are confronted with the complexity of psychiatric problems, the past traumatic experiences and the present living problems. However, there is no need for such feelings.

When I arrived in post-Biafra Nigeria (1983), I expected a lot of trauma-related problems but I discovered that only a few of my patients had such problems and only a few were known in the villages as war-affected persons. I discussed this with a nurse and she asked me: ‘Well doctor, don’t you know the law of the bamboo? When the wind blows strong you bow and when she is quiet again you bounce back’. Later I learned that the ability to bounce back from hardship and trauma is usually described as resilience.

Resilience: the ability to sustain and to recover

Scientific research confirms that the majority of individuals survive all sorts of hardships with minimal distress, or with the ability to tolerate their distress, and move on with their lives in a positive manner. How are they able to do so? Hobfoll developed the conservation of resource theory (COR-theory). [2,3] This theory implies that if people are able to regain their material, psychosocial and financial resources after experiencing adversities the chances of developing psychopathology are much less. Southwick and Charney interviewed a variety of groups of trauma-survivors and found ten, what they call “resilience factors”: realistic optimism, facing fear, moral compass, religion and spirituality, social support, resilient role models, physical fitness, brain fitness, cognitive and emotional flexibility and meaning and purpose. [4,5,6]

This new knowledge is important in the prevention of psychopathology, but it is also helping to shape treatment programmes.[7,8]

With regard to asylum seekers and refugees we propose the following definition of resilience: the capacity to maintain or regain health and function ability despite past experiences and to endure stressors of the asylum procedure and all daily living hassles (post-migration living problems). [9,10]

Trauma-focused and resilience-focused interventions

Epidemiological research shows high prevalence rates of psychopathology among asylum seekers and refugees.[11] Next to the traumatic experiences in their country of origin, they face many challenges, disappointments and adversities in the host country. Research among asylum seekers showed that the length of the asylum procedure has a higher risk for psychopathology compared to the traumatic experiences in the past.[12] In both asylum seekers and refugees the acculturation process, intergenerational difference in this process, language problems, discrimination, financial problems, worries about the family back home, lack of a solid social network and in many cases unemployment, are issues which all interfere with the treatment. In searching to find the most effective and suitable therapy these day to day stressors cannot be neglected. The debate of what kind of treatment should be given to asylum seekers and refugees is still going on. Nickerson et al. observe two contrasting approaches, namely trauma-focused therapy and multimodal intervention.[13] The trauma-focused approach is grounded in the contemporary cognitive behavioural framework, while the multimodal intervention tries to address not only the psychological reactions that may occur after traumas but also subsequent psychological stressors, physical health problems and resettlement and acculturation challenges. They conclude that ‘trauma-focused approaches may have some efficacy in treating PTSD in refugees, but limitations in the methodologies of studies caution against drawing definitive inferences’. In their recommendations for further studies they emphasize the importance of recognizing the context of treatment delivery in terms of ongoing threats, the feelings of grief, anger over past injuries and the myriad of psychosocial difficulties with the resettlement process.

A resilience-oriented approach encompasses both trauma-focused therapies and multimodal interventions: trauma-focused therapies can be added to a resilience-focused treatment programme, when needed, acceptable and possible.

The ROTS model

In the daily work with asylum seekers and refugees the psychiatrists and other staff members in the North Netherlands Centre for Transcultural Psychiatry De Evenaar, make use of the so-called ‘resilience-oriented therapy and strategies’ model (ROTS).

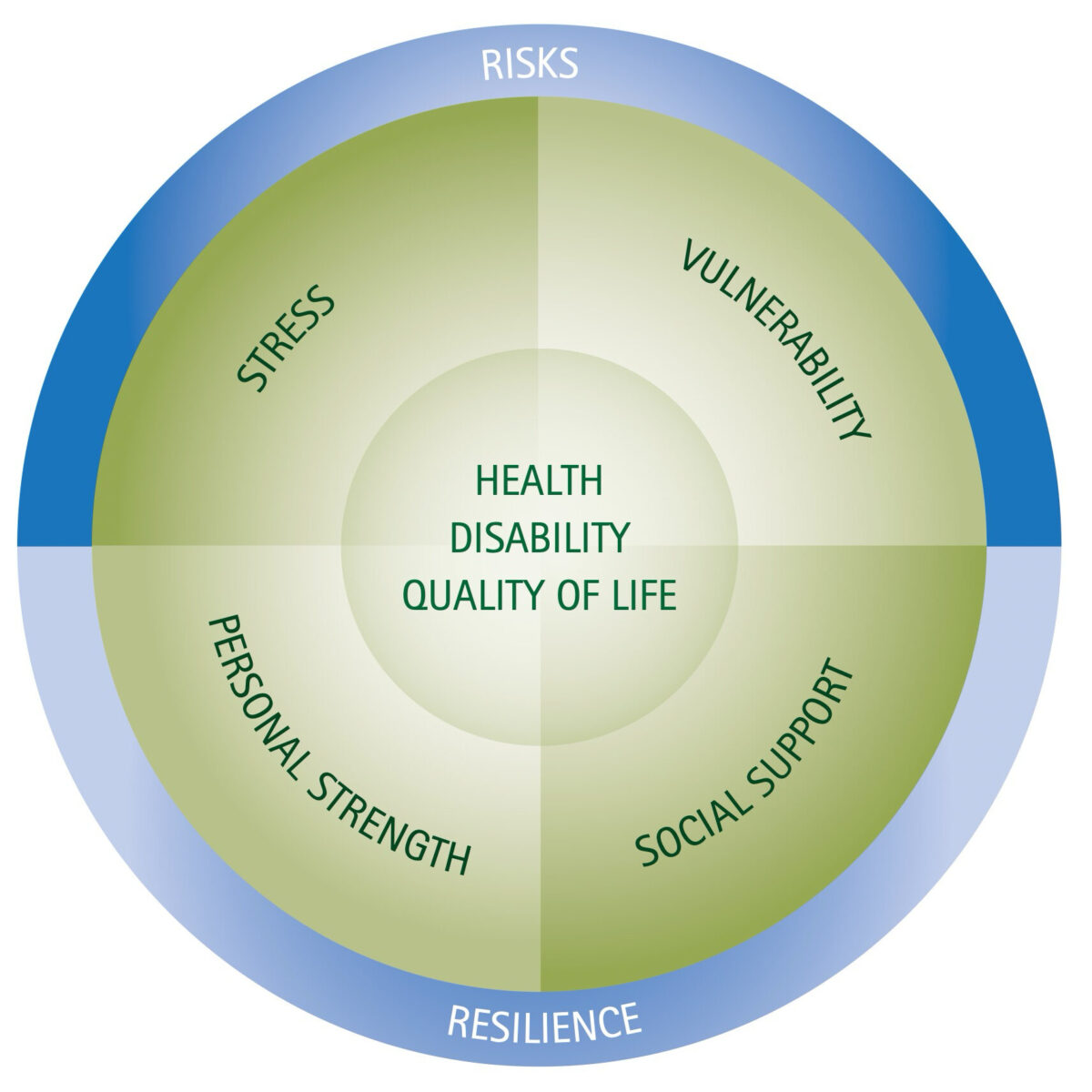

This model (adapted from De Jonghe et al.) [14] brings together the concepts of vulnerability and stress and two aspects of resilience, i.e. personal strength (e.g. coping) and social support.

The model is an expansion of the well-known stress-vulnerability model developed by Zubin and Spring. [15]

Vulnerability and strength are personal characteristics (internal factors) and stress and social support are ecosocial characteristics (external factors). The central question in shaping the treatment plan is: what can be done to lower the stress and vulnerability and what can be done to increase resilience (i.e. social support and personal strength). Working with this model means that during the first assessment the health complaints and the experienced traumas are explored as usual, but at the same time a lot of attention is given to the resources of personal strength and social support. Based on findings in the literature and on our own clinical experience, the resources of resilience can be classified according to the biopsychosocial model: biological (physical exercise, understanding the body, relaxation, treatment of medical illnesses), psychological (positive emotions and humour, acceptance, cognitive flexibility, empowering self-esteem, active coping), social (social relatedness, reconnecting the family, creating and enhancing social support). In order to make the model suitable for the asylum seekers and refugee population two kinds of resources are added: cultural (cultural identity, acculturation, language skills), and religious/spiritual resources.[9,10]

Research makes clear that there is great diversity in ways people are coping with and ‘bounce back’ from adversities. So the very starting point in the investigation of vulnerability and resilience is the perspective of the patient. In anthropological terms this refers to the so-called emic approach. In clinical practice the cultural interview developed by Groen* is used to include the cultural and religious aspects in this approach. In the resilience-oriented assessment and interventions this interview is an important tool. E.g. discussing cultural identity very easily opens the subject of self-esteem and discussing the psychosocial environment relates directly to the social support system.

The ROTS model has shown its effectiveness in the treatment of traumatized asylum seekers and refugees because the model emphasizes the healing ability (resilience) of the patient, helps in finding protective, supporting and strengthening factors, challenges to investigate a broad scope of interventions tailored to the individual situation and characteristics of the patient, is very easy to explain to staff members as well as to patients and their families, gives a shared frame of reference and involves the patient in his or her own healing and/or surviving process.

Conclusion

The problems of asylum seekers and refugees are numerous and a high percentage has or develops physical and mental health problems. Treatment possibilities are limited due to the experienced complex traumas, the ongoing stress and the existence of comorbidity of stress-related psychiatric disorders. Notwithstanding these limitations, however, treatment is possible. A resilience-oriented diagnostic and treatment model in which the concepts of stress, vulnerability and resilience (distinguished in personal strength and social support) are incorporated is very well applicable in all treatment modalities with asylum seekers and refugees. Tropical doctors are trained in the public health perspective and know the importance of the eco-social environment and the frame of meaning of their patients. These are all beneficial in the work with asylum seekers and refugees and connect naturally to a resilience-oriented approach. Some additional advices for daily practice are: investigate the domains of stress, strength, support and vulnerability, get to know your patient using an attitude of respectful curiosity, never isolate complaints from the person, observe the patient in her/his context, search with your patient for resources of resilience, be a resource of resilience yourself and very important: never lose hope for improvement.

* This interview is based on the Cultural Formulation of Diagnoses DSM-IV. The new DSM-version (DSM5) contai

References

- e.g. Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience; Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 2004;59: 20-8.

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol 1989;44:513-24.

- Hobfoll SE, Mancini AD, Hall BJ et al. The Limits of Resilience: Distress, Following Chronic Political Violence among Palestinians. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1400-8.

- Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS. The psychobiology and resilience to stress: Implications for prevention and treatment. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:255-91.

- Southwick SM, Litz BT, Charney D, Friedman MJ (ed). Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges across the Lifespan. Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, 2011.

- Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges. Cambridge University. Press, New York, 2012.

- Kent M, Davis MC, Stark SL et al. A resilience-oriented treatment for post traumatic stress disorder: Results of a preliminary randomized clinical trial. J of Traumatic Stress 2011:24:591-5.

- Kent M, Davis MC. Resilience training for action and agency to stress and trauma; becoming the hero of your life. In: Kent M, Davis MC, Reich JW (ed): The resilience handbook; approaches to stress and trauma. Routledge, New York, London, 2014, pag. 227-44.

- Laban CJ. Dutch Study Iraqi Asylum Seekers: Impact of a long asylum procedure on health and health related dimensions among Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands; An epidemiological study. Proefschrift VU, Amsterdam 2010, Chapter 8. http://dare.ubvu.vu.nl//handle/1871/15947

- Laban CJ, Attia A, Hurulean E. Asielzoekers en vluchtelingen In: Joop de Jong, Sjoerd Colijn (red.). Handboek Culturele Psychiatrie en Psychotherapie. De Tijdstroom, Utrecht, 2010, p. 563.

- e.g. Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2005; 294(5):602-12.

- Laban CJ, Gernaat HB, Komproe IH, et al. Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. J Nerv Ment Dis, 2004;192:843-51.

- Nickerson A, Bryant RA, Silove D et al. A critical review of psychological treatments of posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31, 399-417.

- Jonghe F de, Dekker J, Goris C. Steun, stress, kracht en kwetsbaarheid in de psychiatrie. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1997.

- Zubin J, Spring B. Vulnerability: A new view of schizophrenia. J of Abnormal Psych 1977;86:103-26.

- Groen SPN. Een nieuwe versie van het culturele interview. Toepassing en evaluatie van een vragenlijst voor een cultuursensitieve diagnostiek in de GGZ. Cultuur, Migratie en Gezondheid 2008;5:96-103.