Main content

The climate crisis unequally af-fects low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) causing natural disasters, the spread of infectious diseases, and environmental pol-lution.[1] These countries contribute to substantially fewer emissions responsible for causing the climate crisis than high-income countries. Meanwhile, LMICs have fewer op-tions to protect themselves against ecological threats.

Rising temperatures due to global warming cause an increase in heath related morbidity and mor-tality. Moreover, rising tempera-tures and extreme weather events like flood and drought influence drinking water quality as well as crop and livestock productivity. These natural disasters lead to food insecurity, water stress and eventu-ally forced migration. The number of climate refugees is predicted to reach more than one billion by 2050. Also, countries that experi-ence lots of ecological threats have a relatively high number of con-flicts.[1,2]

Health paradox

The healthcare system contributes a great deal to carbon emissions linked with the climate crisis. The Dutch healthcare sector is responsible for as much as 7% of national CO₂ emis-sions.[3] This implies a health paradox: on one hand, the healthcare sector promotes health and provides treat-ment for disease, while on the other hand it contributes to the climate crisis causing CO₂ emissions, which have a detrimental impact on global health.

Green deal

In 2018, more than 150 healthcare organisations signed the Green Deal (2.0) in the Netherlands, a pledge for more sustainable healthcare. The Green Deal is divided into themes, or pillars: reducing CO₂ emissions (pillar 1), producing less waste and reusing more materials and products, also called circularity (pillar 2), ensuring that less residual medicine finds its way into waste water (pillar 3) and promot-ing a healthy environment.[4] We will describe these four themes of the green deal in detail below. These themes play an important role in the Dutch health-care system with its disposables and prescriptions for chronic diseases, and on a smaller scale in tropical medicine settings.

Co₂ reduction

Annually the Dutch healthcare sector emits eleven megatons of CO₂. Most of these CO₂ emissions result from energy consumption (like heating and lighting) of buildings (38%), travel of patients and commuting traffic of healthcare workers (22%), and drug production (18%).[3] These numbers include emissions from supply chains. Energy use varies greatly between hospitals. Generic measures such as insulating buildings and using renewable energy and energy-efficient devices provide opportunities for huge reductions. In the travel category, health-care workers cause most emissions. Therefore, changing their transporta-tion methods and working (partly) from home are important themes to decrease the use of fossil fuels. Additionally, international conferences cause a huge amount of CO2 emissions from flights by participants.[5] Online conference attendance dramatically reduces emis-sions by eliminating air travel. In drug production, the part responsible for the biggest emission of CO₂ is production of the required raw materials. Switching to less harmful alternatives is particularly important for inhalers and anaesthet-ics. Inhalational anaesthetics are very potent greenhouse gases and can be replaced by intravenous options.[6]

Circularity

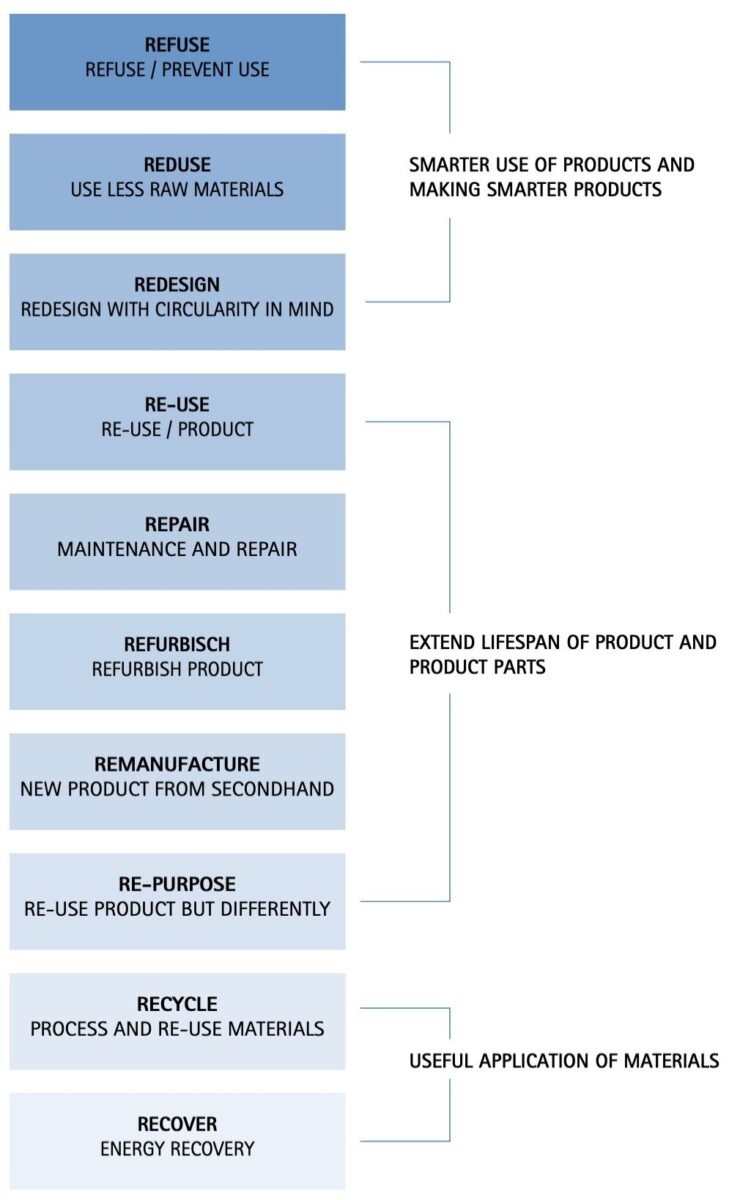

Circularity means a closed loop of continuous reuse of resources, where no waste is created. Mining of raw materi-als is associated with negative effects on the climate and poor working conditions with exposure to environmental health hazards in the mining countries. In the Dutch healthcare system, a lot of (mainly plastic) waste can be recycled. Instead, most waste is currently burned, which results in CO₂ emission. Waste that ends up in the environment pollutes water and soil with harmful substances or (micro)plastics. Circularity is not just recycling. In fact, recycling is just one of the last steps in circularity. The Utrecht Sustainability Institute developed a ten-step priority scheme (Figure 1).[7] The shorter 3R principle is well known: reduce, reuse, recycle. The most impor-tant steps include: reduced demand for materials, increased life span, reusing and ultimately recycling materials. An average Dutch hospital bed pro-duces 250 to 300 kg waste per year [8], emphasising the urgent need to rethink how we purchase and use disposables and handle waste in health care.

Residual medicine in waste water

In addition to the harmful effects of drug production as explained in the first pillar (CO₂ reduction), drugs can also be harmful after use. Annually, a total of 190,000 kg of human drugs and drug waste (degradation products)[9] enter the waste water system in the Netherlands. Many drug degradation products are eliminated via patients’ urine and faeces. Waste water filtration systems were not designed to filter medication, and approximately 35% of waste water drugs end up in open waters. These drugs and drug waste disturb biodi-versity in the water. Although concen-trations are generally low, the effect appears to be substantial. Only a few drugs are subject to European norms for safe concentrations, and the environ-mental effects of many drugs and their degradation products are unknown.

Antibiotics affect cyanobacteria, and antidepressants affect the behaviour of various organisms.[9] Tap water contains low concentrations of drugs and radio-logic contrast agents. Concentrations in tap water are expected to increase due to the aging population and the expected increase of medication use in the future. Higher concentrations are probably needed to affect human health, but the effect of long-term exposure to low (but increasing) concentrations of these sub-stances is unknown. This could possibly make water temporarily unsuitable for drinking water preparation in future.

In the case of residual medicine in waste water, a collective approach is important. Various actions need to be taken within the framework of production, prescrip-tion and water purification strategies.

Many clinicians and healthcare profes-sionals argue for strengthening preven-tive medicine and treating diseases with lifestyle changes. This eliminates the need for medicine and therefore reduces residual medicine in waste water and CO₂ emissions in general.

Healthy environment

A healthy environment improves the wellbeing and health of patients and healthcare workers. Patients in a natural environment required less analgesics after surgery.[10] Green rooftops on hospital buildings improve insulation, temperature manage-ment, biodiversity and noise levels.[11] Sustainable and healthy nutrition is documented in the Nationaal Preventieakkoord. Naar een gezonder Nederland (National Prevention Agreement for a healthier Netherlands), which states that all Dutch hospitals should serve mainly healthy food by 2030. Nutrition has a major effect on CO₂ emission, specifically through food waste and the use of animal products. By eliminating meat consumption, you can halve your nutritional CO₂ foot-print.[12] In conclusion, a healthy envi-ronment contributes to the reduction of the psychological effects of illness: stress, anxiety and (un)wellbeing.

What can we do?

The healthcare sector can and should be more sustainable. The climate crisis is an undeniable threat to public health. As healthcare professionals, we therefore have an important task in the fight against climate change. For young doctors, mostly working in temporary positions, the climate crisis may feel so overwhelming that they might doubt the impact of their small actions. However, they can make a dif-ference immediately: by changing small daily routines, inspiring colleagues, contributing to a green initiative, or by setting up a sustainable project.

| Practical tips Consider the online option for your next conference and participate together with local colleagues. Commit to separating waste at your workplace, particularly plastic and non-contaminated waste. Bring your own water bottle and coffee cup instead of disposable cups. |

De Jonge Specialist (The Young Specialist), the professional association for physicians in training for a specialty and physi-cians not in training for a specialty in the Netherlands, launched a committee – the Green Healthcare Committee – of young green-hearted doctors to bring sustain-ability to the attention of its members. The Green Healthcare Committee published a guide with practical tips, inspiring examples and green pioneers collected from throughout the Dutch healthcare system. This guide, called Groen, groener, groenst: handreiking voor a(n)ios die de zorg willen verduurzamen (Green, greener, greenest: a guide for physicians in training for a specialty and physicians not in training for a specialty who wish to make healthcare more sustainable), is a leading document to inform and motivate young doctors to contribute to a greener healthcare system. Be inspired and shoulder your responsibil-ity as a healthcare professional! The guide is written in Dutch and can be found here www.dejongespecialist.nl/2021/de-jonge-specialist-gaat-groen-groener-groenst/.

References

- Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet. 2021 Jan 9;397(10269):129-70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-Χ.

- Institute for Economics & Peace. Ecological Threat Register 2020: understanding ecological threats, resilience and peace [Internet]. Sydney: IEP; 2020 [accessed 2021 Dec 13]. 95 p. Available from: www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ETR_2020_web-1.pdf

- Gupta Strategists. Een stuur voor de transitie naar duurzame gezondheidszorg: kwantificering van de CO₂-uitstoot en maatregelen voor verduurzaming [Internet]. Amsterdam: Gupta Strategists; 2019 [accessed 2021 Jul 26]. 33 p. Available at: www.gupta-strategists.nl/storage/files/1920_Studie_Duurzame_Gezondheidszorg_DIGITAL_DEF.pdf.

- Green Deal. Duurzame zorg voor een gezonde toekomst. Available at: www.greendeals.nl/green-deals/duurzame-zorg-voor-gezonde-toekomst. [Accessed 26 July 2021].

- Bousema T, Selvaraj P, Djimde A, et al. Reducing the carbon footprint of academic conferences: the example of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 Nov;103(5):1758-61. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1013

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie. 13 adviezen om als vakgroep anesthesiologie de OK te vergroenen [Internet]. Utrecht: NVA; 2021 [accessed 2021 Jul 26]. 9 p. Available from: www.anesthesiologie.nl/uploads/files/NVA_Handreiking_13_Adviezen_om_de_OK_te_verduurzamen.pdf

- RVO [Internet]. Assen, Den Haag, Utrecht, Roermond, Zwolle: Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland; 2021. R-ladder – strategieën van circulariteit; updated 2021 Apr 28 [accessed 2021 Jul 26] Available from: www.rvo.nl/onderwerpen/duurzaam-ondernemen/circulaire-economie/r-ladder

- Möbius [Internet]. Sint-Martens-Latem, Brussel, Utrecht, La Madeleine: Möbius Business Redesign; 2022. Dewickere D, Hoe verlaag ik als ziekenhuis de financiële- en milieu-impact van mijn afval? [accessed 2021 Jul 26]. Available from: www.mobius.eu/nl/blog/hoe-verlaag-ik-als-ziekenhuis-de-financiele-en-milieu-impact-van-mijn-afval/

- Moermond CT, Smit CE, Van Leerdam RC, et al. Geneesmiddelen en waterkwaliteit [Internet]. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; 2016 [accessed 2021 Jul 26]. 96 p. Briefrapport: 2016-0111. Available from: www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/2016-0111.pdf

- Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984 Apr 27;224(4647):420-1. doi: 10.1126/science.6143402

- Green Deal Groene Daken. Facts and values groenblauwe daken [Internet]. Green Deal Groene Daken; 2019 [accessed 2021 Jul 26]. 2 p. Available from: www.greendealgroenedaken.nl/facts-values/

- Milieu Centraal [Internet]. Vlees, vis of vega; [accessed 2021 Jul 26]. Available from: www.milieucentraal.nl/eten-en-drinken/milieubewust-eten/vlees-vis-of-vega/