Main content

Ed Zijlstra served as editor-in-chief (ad interim) for three years, from 2020 to 2023.

It has been a pleasure to serve as a member of the MTb editorial board and editor-in-chief ad interim. I am most grateful to all my fellow editors and to all those who contributed to MTb for their commitment and expertise. The thematic approach proved to be attractive, and the digital library may serve as a source of reference.

I have selected Medical Education in Global Health and Tropical Medicine as the topic for this contribution as it offers an opportunity to compare, contrast and unify efforts in this field. From the Global South, I take the College of Medicine (now: Kamuzu University of Health Sciences [KUHeS]) in Malawi as an example, and from the Global North the training programme for Physician of Global Health and Tropical Medicine (PGHTM) in the Netherlands, now renamed Medical Doctor Global health (MD-GH). What can we learn from the past and from each other?

Medical education in Malawi

The College of Medicine in Blantyre, Malawi, can be seen as a success story in medical education in Africa to which many partners contributed, including the Netherlands Support Program, funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. [1,2] Whereas in 1982 a delegation of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Malawi Minister of Health agreed on establishing a medical school and decision to take this forward was made in 1986 by the former Head of State Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda, it was not until 1991 that the school was actually established: the Malawi College of Medicine (CoM) in Blantyre, under the umbrella of the University of Malawi (UNIMA). [2,3] The CoM adopted the format of a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) programme. The first years followed a phased approach in which the first group of students who had completed their pre-clinical sciences in the United Kingdom, Australia or South Africa continued their clinical rotations (junior/senior clerkship and internship) in Malawi at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Blantyre. (Figure 1) In 1998, the first batch of students graduated who had been fully trained in Malawi. [1] The curriculum consisted of the classical format starting with two years of basic sciences; the third year focused on pathology, community health, and junior clerkships, with a research elective in year 4, and senior clerkships and the final MBBS exams in year 5. The curriculum was revised in 2008, with clinical teaching already integrated from year 1.

* Ed Zijlstra is Professor of Medicine and Former Head (1998-2009) of the Department of Medicine, College of Medicine (now: Kamuzu University for Health Sciences [KUHeS]) and was as such responsible for the undergraduate and postgraduate programme. He was chairman of the Concilium International Health and Tropical Medicine (Concilium Internationale Gezondheidszorg en Tropengeneeskunde) from 2015-2022 and chair of the Committee to review the Training Programme for Physicians Global Health and Tropical Medicine (CHOA) from 2018-2019.

The number of first-year students increased from initially 30 to 60 and later 100, with facilities both in Blantyre and Lilongwe.

After obtaining the MBBS, an internship of 15 months duration follows under the umbrella of the Ministry of Health, with clinical rotations in each of the major departments for 3 months. After this, the student may be registered with the Malawi Medical Council. [4]

The MBBS curriculum has always been community-oriented, and all students spend time every year in the CoM annex at Mangochi, along the shore of Lake Malawi for designated teaching. Quality of the teaching programmes is taken very seriously; every two years a curriculum review was organised for which national and international experts were invited. Second, for the final year examinations an external examiner was invited for each department to moderate the written paper and to attend the clinical examination sessions. The reports were discussed in the Board of Examiners meeting, and recommendations for improvement were formulated.

Postgraduate training

After the first postgraduate programme in Public Health started in 2003, the clinical departments followed in 2004 and offered Master of Medicine (MMed) courses in Internal Medicine, Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Anaesthesia and Ophthalmology. These programmes consist of a part I and part II (two years each) as well as a dissertation. For the Department of Medicine, for example, during part I, the students work as registrars in the department supervised by senior staff. There is protected time for teaching. After passing the part I examination, part II followed, preferably in a country where the specialty is practised at the highest level. This is because the support services at CoM/QECH were not adequate to support clinical exposure. South Africa was in an excellent position, as it has the high level of care needed to provide a benchmark for the trainees, and a similar pathology as in Malawi as well as all other conditions relevant in high-income countries. Initially, these posts were funded by the National AIDS Commission (NAC), anticipating the need for specialists to deliver care for patients with HIV/AIDS.

Staff development

In the first decade of the 21st century, the Netherlands Support Program from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs provided specialists in Internal Medicine, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Surgery (including Orthopaedics) and Anaesthesiology to help with clinical teaching, as only few Malawian specialists were available. Twenty years after the start of the postgraduate programme, most members of staff are Malawian with subspecialists in plastic surgery, neurosurgery, respiratory medicine, neurology, haematology, pathology, endocrinology and renal medicine, among others.

A new university

The Kamuzu University of Health Sciences (KUHeS) was established in 2021, in which the CoM and the Kamuzu College of Nursing (KCN) were amalgamated and became independent of the University of Malawi. This created more flexibility for expanding and budget control. KCN was established in 1983 and delivers a three-year university diploma followed by a one-year certificate in midwifery. [5] Other programmes in KUHeS include training for pharmacists, physiotherapists, and laboratory scientists.

Regional training – internal medicine as an example

The East, Central and Southern Africa College of Physicians (ECSACOP) was established in 2015 because of a shortage of internists in participating countries: Zimbabwe, Zambia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Malawi. For a population of 250 million, there are 1000 internists: a ratio of 1:250,000, whereas the WHO norm is 1:1000 population.

The ECSACOP provides a full-time training programme (fellowship) in carefully selected accredited training sites in each of the participating countries. The aim is to train locally, prevent unnecessary migration, benefit from each other’s expertise, and aim for regional harmonisation; a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) is created. There is an annual congress in which a ceremony is held for awarding the diplomas to those who have successfully completed the programme, thus qualifying for the title of Fellow of the East, Central and Southern Africa College of Physicians. (Figure 2) The programme is supported by the Royal College of Physicians of the United Kingdom (RCP) and the Africa office of WHO (WHO-AFRO). Currently, a debate is ongoing whether to keep the training limited to generalists in internal medicine or to proceed with subspecialties such as infectious diseases, renal medicine, endocrinology, etc.

| Regional colleges that offer training in Africa COSECSA – College of Surgeons for East, Central and Southern Africa ECSACOG – East, Central and Southern College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology CANECSA – College of Anaesthesiologists of East, Central, and Southern Africa ECSAPACH – East, Central and Southern Africa College of Paediatrics and Child Health ECSACOP – East, Central and Southern Africa College of Physicians |

Research

The CoM / KUHeS has always strongly promoted excellence in research and collaborates with partners such as in the Malawi-Liverpool-Welcome (MLW) programme and the Johns Hopkins Institute. Increasingly, research focuses on topics of direct relevance to public health and clinical care delivery such as malaria, HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. Increasingly, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are also being addressed. Publications from Malawi abound in the medical literature. Research proposals need approval by the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC). A Research Dissemination Conference is organised annually to provide a forum for (young) researchers to present their work.

In conclusion, setting up a medical school in Malawi was successful because of continuing political commitment, strong leadership – including a vision for the future – and varied international donor support.

The training programme for the Dutch physician in global health and tropical medicine: a critical appraisal

Introduction

The Netherlands Society of Global Health (NSGH) organises a unique training programme for Medical Doctor in Global Health (MD-GH). The training programme was started in the 1950s, and in 2014 was recognised by the Royal Dutch Medical Association as a physician profile. It is a professional career step, not an added-on training. The programme prepares you to work as a medical doctor, advisor in public health, teacher or manager, or combinations. It consists of a mix of public health and clinical teaching and takes 2 years and 9 months to complete. (Table 1) It has a classical profile with core training in the Netherlands in accredited hospitals in surgery and O&G, both for 1 year; alternatively, a mother and child profile of O&G and paediatrics may be selected. This is followed by the mandatory Netherlands Tropical Course on Global health and Tropical Medicine (NTC) (3 months), which has a strong public health teaching component, covering disease control and prevention as well as health systems, finances, social and cultural issues, and ethics, among others. There is also theoretical teaching in clinical subjects. There are 10 additional 1-day training courses in overarching topics (e.g., transcultural rehabilitation, ophthalmology, or dental pathology). After the NTC, a 6-month supervised global health residency follows in a low-resource setting (LRS) to consolidate what has been learned and to gain experience under supervision. This residency is not structured and may differ considerably among candidates.

A In this article, the former abbreviation of PGHTM will be used: Physician Global Health and Tropical Medicine for alignment with reports quoted in this paper.

B Now replaced by the Core Course in Public Health and Health Equity (CCPH-HE).

| Phase | Duration | Content | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 12 months | Surgery or Paediatrics | Dutch hospital accredited by RDMA |

| 12 months | O&G | Dutch hospital accredited by RDMA | |

| Phase 2 | 3 months | Course in Global Health and Tropical Medicine (NTC)2 | Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) |

| Phase 3 | 6 months | Global Health Residency | Hospital/organisation in LRS accredited by OIGT |

Challenges: gaps in the curriculum, assessment, ethical considerations and outlook

Gaps in the curriculum

The training profile of the PGHTM is seriously outdated, as it goes back to the 1980-90s. This pertains to the lack of formal clinical training in Internal Medicine (for all) and Paediatrics (for those in the classical profile). In LMICs, these specialties also include cardiology, respiratory medicine, neurology and palliative care, among other.

In 2020, the NSGH commissioned a curriculum review of whether the PGHTMs were adequately trained according to their own perspective as well as from the perspective of the host institute and/or international stakeholders. In the study by Isabelle Tiggelaar et al, Graduates’ perspectives on the Dutch post-graduate training in Global Health and Tropical Medicine: a qualitative study, PGHTMs predominantly worked as clinicians; several were (also) involved in management or capacity building. [6] The clinical training programme adequately addressed general skills, but did not sufficiently prepare for locally encountered, often severe, pathology. While the generalist nature of the PGHTM training was appreciated by graduates, the programme would benefit from additional training on infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases (NCDs – normally the domain of Internal Medicine), and Paediatrics. It was not uncommon that gaps in the curriculum were addressed on the student’s own initiative. These shortcomings led to feelings of a lack of competency and frustration and even burn-out; for some, it was a reason not to continue working in LRS. [6] Students would appreciate exposure to topics in the NTC earlier in the curriculum, while the total duration of the training programme should not be altered. Future outlook included a more prominent role as teacher, and teaching skills could receive more attention during the NTC. [6]

In the study by Jamilah Sherally et al, The Dutch postgraduate training in global health and Tropical Medicine: international stakeholders’ perspectives, the theoretical knowledge of PGHTMs upon arrival was reported to be excellent; consolidation of skills and understanding of the local context were predominantly developed on the job. [7] More emphasis could be placed on NCDs, mental health, public health, development managerial skills and socio-cultural factors. The need for bilateral exchange and mutual ownership were emphasised.

The changing scope of tropical medicine and global health

While surgery and O&G have always played a major role (and still do so today), at the end of the 20th century, infectious diseases became a specialty in internal medicine and paediatrics. Previous optimism about, for example, infection treatment and control by antibiotics and control of malaria by chloroquine treatment and DDT spraying dissipated; malaria cases surged with high mortality particularly in children under the age of five years; antibiotic resistance emerged with force and continues to date. The HIV pandemic that started in the 1980s brought on a huge burden of infectious diseases. Initiated by Médecins Sans Frontières, Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) were widely recognised as a serious neglected entity; this led to the establishment of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (Geneva, Switzerland) as there was a huge gap in research. [8] Major outbreaks of thus far unknown pathogens occurred as well as the return of forgotten infections. Antimicrobial resistance has become an increasing world-wide problem. This led to the concept of Emerging Diseases. (Table 2)

In 2011, the second meeting ever organised by the United Nations at the level of Heads of State was on NCDs (the first one in 2001 on HIV/AIDS). It is widely recognised that most deaths due to NCDs are in low- and middle-income countries. The NCDs have always been important in LMICs but have been seriously neglected/overshadowed by the HIV and tuberculosis epidemics. They include, among other, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), asthma/COPD, cardiovascular disease and oncology. These are interrelated with other conditions; heart failure may be the result of acute rheumatic fever or HIV-related viral infections; cancer is common in HIV/AIDS and may include Kaposi’s sarcoma (caused by human herpes virus [HHV-6]), cervical carcinoma (human papilloma virus [HPV]), or lymphomas (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]). Hepatitis B and C cause liver cirrhosis while schistosomiasis causes periportal fibrosis. HIV increases the risk of stroke. The incidence of NCDs such as hypertension and DM increases with increasing obesity as the result of adopting western lifestyle and dietary habits, while DM may increase the risk of infections; an integrated approach is advocated. [9, 10]

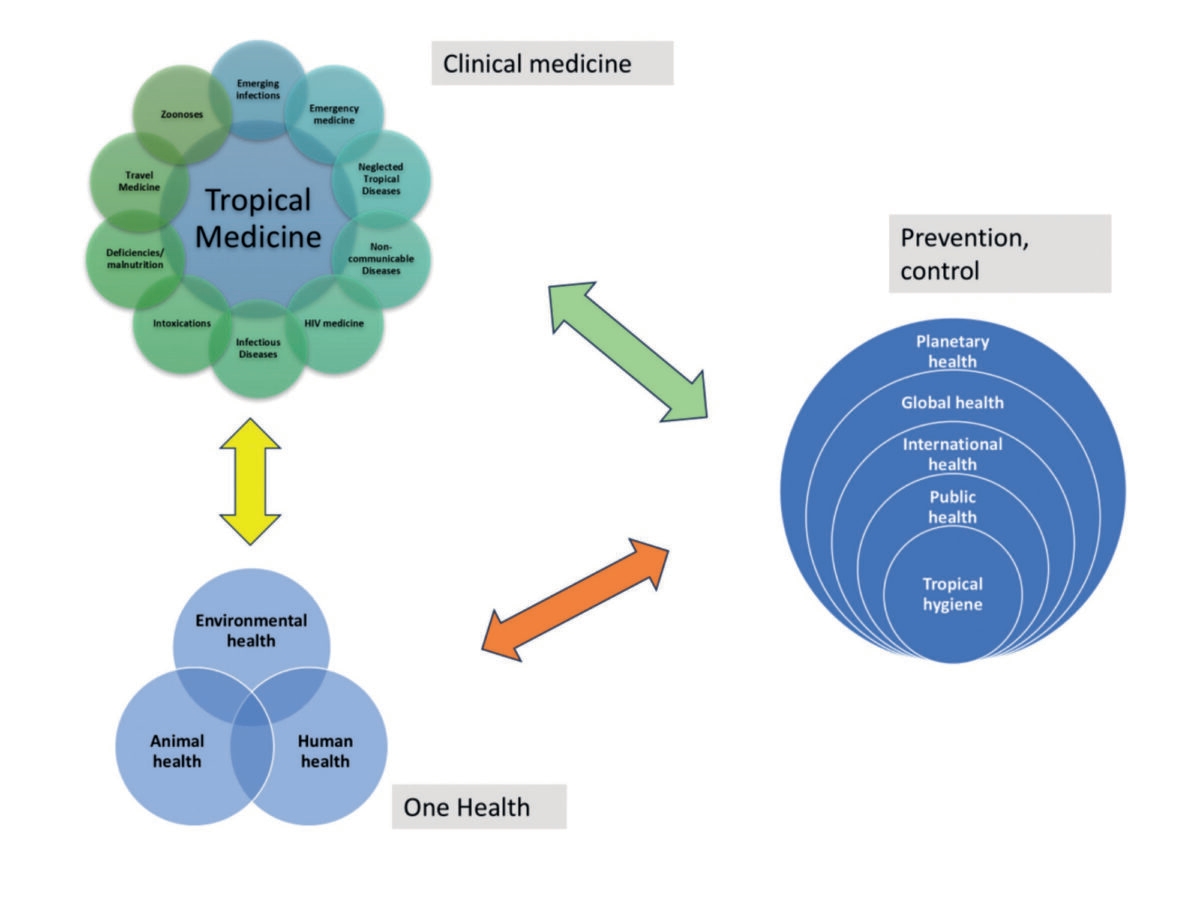

The field of Tropical Medicine has expanded since Patrick Manson defined this specialty around 1900. While it included exotic diseases that occurred in warm climates and were associated with poverty, nowadays, it includes a spectrum of conditions and has a strong relationship with Global Health and One Health (Figure 3). Tropical Medicine may be considered as (Internal) Medicine in the tropics. Health workers who prepare for work in LRS should have knowledge about the different pathology compared to the Global North, and it may also vary per tropical region. For example, pathology and public health issues encountered in Thailand are different from those in Malawi or Ecuador. Knowledge about and adapting to a setting with different cultures, health systems and politics is essential. Tropical medicine should not be confused with or replaced by Global Health. While the concept of Global Health is valid, it seems a typical high-income country concept, and clinical medicine does not feature prominently; public health predominates as seems also to be the case in the PGHTM training. [11] Using Global Health and Tropical Medicine jointly (and jointly with One Health) adequately addresses differences as well as the overlap and is widely used, among others, to designate courses and scientific societies.

Assessment

Assessment relies heavily on awarding of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) that are based on the CANMeds competencies. EPAs include professional activities or competencies entrusted by senior staff for trainees to perform activities without or with limited supervision once these competencies have been acquired. The Netherlands Association of Physicians (NIV), for example, has 4 compulsory EPAs (ward-based work, outpatient clinic, consultations and on-call duties) reflecting 4 different patient populations and activities. [12] Acquiring EPAs should not be seen as a goal but as a means to support professional growth and to learn to work independently. Supervision is essential. [12]

Clearly the EPAs should be awarded by senior specialists in a setting of well-structured training such as the residencies in Surgery, O&G and Paediatrics. In the current training programme, EPAs for Internal Medicine (all trainees) and for those who do not do Paediatrics are awarded by the OIGT by proxy based on continuous quality assessment of the host institution.

Ethical considerations

Taking Malawi as an example, graduates from the undergraduate programme do junior and senior clerkships (each 6 weeks) in all 4 main departments (Internal Medicine, Paediatrics, Surgery, O&G;) and sit for the final MBBS exam. This is followed by an internship of three months in the same departments in which they do clinical work under supervision, before being registered with the Malawi Medical Council. In comparison the PGHTM only have formal supervised clinical training in the two profiles and lack clinical skills and experience in subjects that are not covered. Despite this, they work as generalists covering and treating patients in all four major disciplines. This touches on professional ethics and should be discussed with the regulatory authorities in the Netherlands and the host country.

Outlook

The current curriculum needs to be reviewed regarding training in clinical medicine:

- The need for PGHTMs should become clear from the two studies quoted.

- The emphasis of activities may shift from clinical work to teaching for which adequate skills are required.

- All necessary skills needed should be provided in the training programme and not left to the initiative of the individual student (harmonisation).

- The student should be adequately equipped and be self-confident (skills, remote support, etc) to avoid frustration and burn-out.

In the review of the PGHTM training programme, the following may be considered (see also ref [13])

- CLINICAL TRAINING

a. All clinical training must take place in an accredited hospital setting.

b. It is essential that the PGHTM should have at least the same level of clinical exposure as the graduates from LRS and the CoM / KUHeS in Malawi in their junior and senior clerkship and internship; additional exposure at postgraduate level for 3-6 months may be needed. This would apply to all four major clinical specialties.

c. Keeping the current format of 2 years of clinical exposure would mean 4 attachments of 6 months each in an accredited hospital (broad baseline training).

d. The time allocated for training in Surgery and O&G in the current curriculum may not be necessary for everyone, particularly for those who will work in management or not in a low-resource setting, where it would seem a waste of time and resources. For most positions, limited training is sufficient, for example for Surgery in traumatology / emergency medicine as well as wound care, and for O&G obstetric emergencies. In many settings, ample expertise is available locally (consultants, experienced clinical officers) as well as options for rapid consultation (e.g. WhatsApp groups to that effect) and referral. In other remote settings, much more extended training is necessary to work independently. Early differentiation in a full or limited training may be considered (differential or modular training).

e. Training in Emergency Medicine should be compulsory (e.g. for 6 months) as the student would acquire quick and efficient diagnostic and management skills across all clinical specialities. It will provide triage skills and offers opportunities to train in traumatology, and all clinical emergencies as well as in additional skills such as drainage of ascites, pleural or pericardial fluid, performing bone marrow aspirates and ultrasound (limited emergency medicine-based curriculum).

f. An alternative and novel approach would be to make the entire clinical training Emergency Medicine based, in which the student would have a supernumerary appointment in the clinical departments to be able to follow up the patients admitted and to interact with the staff as well as to attend ward rounds, clinics and training sessions in each department (extended emergency medicine-based curriculum).

g. Another option would be differentiation in medical specialties (Internal Medicine and Paediatrics) and surgical specialties (Surgery and O&G) (dual limited specialist training).

h. Lastly, early differentiation may be considered in a single speciality e.g. O&G (specialist training). This would obviously mean the regular formal specialist training and will be outside the PGHTM programme, but with added-on training in Global Health and Tropical Medicine. - THE NETHERLANDS TROPICAL COURSE ON GLOBAL HEALTH AND TROPICAL MEDICINE (NTC)

The course has been replaced by the Core Course in Public Health and Health Equity (CCPH-HE); this course prepares “to systematically analyse and address complex public health issues, covering epidemiology, health system aspects, and broader social determinants of health. The course focuses on health equity in low-resource settings and high-resource settings with disadvantaged populations”. [14]

a. A critical review is needed to compare this with other courses such as the Diploma and Masters’ courses in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene courses such as in London, Liverpool, Antwerp or Hamburg. Does the NTC / CCPH-HE provide the same standard or is it better to do a course abroad?

b. The course topics should be selected in close consultation with public health and clinical experts.

c. For clinical topics: theoretical exposure (lectures) can never replace clinical exposure or experience and cannot form the basis of EPAs.

d. Case-based sessions by experienced specialists contribute to a better understanding of severity and scope of the pathology that the student may encounter in the future; these should be placed early in the curriculum as an introduction to Global Health and Tropical Medicine.

e. The best teachers should be invited from the Netherlands or from abroad. - THE GLOBAL HEALTH RESIDENCY

The content of this attachment should be clear and standardised.

a. A student may select an accredited host institute according to what they can offer e.g. consolidation or advanced training, and/or experience in a certain specialty such as O&G or paediatrics, or a more generalist scope with well-defined supervised rotations in clinical departments.

b. The assessment by the host institute should clearly reflect the activities and performance in each subject according to what was expected.

c. The EPAs for infectious diseases and chronic diseases are awarded by the OIGT based on continuous quality assessments of the host institutes. Using this mechanism as a proxy for (hard) EPAs should be abandoned as it violates the meaning and purpose of awarding EPAs and may be misleading to regulatory authorities. - PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL SATISFACTION; WELL-BEING AND MENTAL HEALTH; CULTURAL ISSUES

a. In the study by Tiggelaar, most PGHTMs report a positive experience of their work in LRS. Others report frustration, feeling of incompetence / inadequate training and burn-out; all these are of serious concern and in part seem related to inadequate training. Professional and personal factors as well as the working environment all may play a role. [6] It should be clear where the PGHTMs can find support in case of mental or social problems.

b. Adapting to a different cultural environment is essential and this should have more emphasis in the curriculum. It is not only about humility, but about respect. [6, 7]

Conclusions

The medical education as offered by the CoM / KUHeS may be taken as an example of clinical exposure needed in this setting in all four major specialties, which should be matched in the PGHTM programme at least at the level of the internship and the first year of postgraduate exposure.

The PGHTM programme is unique and should continue to make a useful contribution to patient care and public health in low-resource settings, but only if its curriculum is credible and acceptable according to standards applicable to the host country. Recent insights will contribute to a thorough review of the curriculum (e.g. in the format of a curriculum conference) with the option for focussed training modules and appropriate assessment.

| Disease | Year | Where * | Principal clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/Aids | Since the 1980s | Pandemic | Immunosuppression Multiple (opportunistic) infections * • Bacteraemias • Sepsis • Respiratory infections including pneumocystis jerovici pneumonia (PjP) • Meningitis • Gastrointestinal infections including S. typhi and non-typhi Salmonella (NTS) • Tuberculosis, pulmonary and extrapulmonary • Cerebral toxoplasmosis • Oesophageal candidiasis • Malaria Malignancies * • Kaposi’s sarcoma • Cervical carcinoma • Lymphomas Neurological • Stroke • Polyneuropathies • Paraplegia |

| Covid-19 CoV-2 | 2019 | Pandemic | Respiratory infection |

| MERS CoV | 2013 | Middle East (mainly Saudi Arabia); imported cases in Europe, Asia, USA | Respiratory infection |

| SARS CoV-1 (South Asia Respiratory Syndrome) | 2002 | South Asia (China) | Respiratory infection |

| Avian influenza H5N1 H7N9 | 1997 2012 | World-wide China | Respiratory infection, systemic illness |

| Ebola | 2014 2025 | West Africa (Sierra Leone) Uganda | Haemorrhagic fever |

| Marburg Virus Disease | 2024 2025 | Rwanda Tanzania (?) | Haemorrhagic fever |

| Dengue | 2013 | Portugal, widespread | Fever, myalgia, headache, rash |

| Chikungunya | 2007 2013 | Italy Caribbean | Fever, poly-arthralgias, rash |

| Zika | 1947 1960-1980s 2015-2016 | Detected in Uganda Asia Americas (Brazil) | Rash, conjunctivitis, arthralgia Congenital birth defects (microcephaly) |

| West Nile virus | 2012 | Europe, USA | Encephalitis |

| Q fever | 2007-2010 | Europe (Netherlands) USA, Asia | Fever, pneumonitis, hepatitis |

* List not exhaustive

References

- Zijlstra EE. The College of Medicine in Malawi: 25th anniversary. Medicus Tropicus bulletin. 2016;54-4:12-6.

- Muula AS, Mulwafu W, Chiweza D, Mataya R. Reflections on the first twenty-five years of the University of Malawi College of Medicine. Malawi Med J. 2016;28(3):75-8.

- Muula AS, Broadhead RL. The first decade of the Malawi College of Medicine: a critical appraisal. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6(2):155-9.

- Manyozo-Phiri MJ, Gumbo E, Nalikungwi R, Muula AS. The Medical Council of Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2001;13(3):48-51.

- Muula AS. The Kamuzu University of Health Sciences: a “semi” new university is born in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2021;33(2):71-2.

- Tiggelaar IG. Dutch post-graduate training in Global Health and Tropical Medicine: a qualitative study on graduates’ perspectives. Medical Education. 2025;25:663.

- Sherally J, Addison J, de Zeeuw J, Versluis M, van de Kamp J, Browne J. The Dutch post-graduate training in Global Health and Tropical Medicine: international stakeholders’ perspectives.; 2023.

- Pedrique B, Strub-Wourgaft N, Some C, Olliaro P, Trouiller P, Ford N, et al. The drug and vaccine landscape for neglected diseases (2000-11): a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e371-9.

- Oti SO, van de Vijver S, Kyobutungi C. Trends in non-communicable disease mortality among adult residents in Nairobi’s slums, 2003-2011: applying InterVA-4 to verbal autopsy data. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25533.

- van Crevel R, van de Vijver S, Moore DAJ. The global diabetes epidemic: what does it mean for infectious diseases in tropical countries? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(6):457-68.

- Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993-5.

- https://www.internisten.nl/de-opleiding/opleiding-tot-internist/.

- Zijlstra EE, van Thiel PP. The needs and requirements of medical doctors preparing to work in the tropics. The role of internal medicine with focus on the Physician Global Health and Tropical medicine (PGHTM) training program. Medicus tropicus bulletin. 2022;59 -1.

- https://www.kit.nl/institute/programme/core-course-in-public-health-and-health-equity-ccph-he/.

Further Reading

Tiggelaar, I. G., Janszen, E. W. M., van Elteren, M., Flinkenflögel, M. M., Sherally, J., Hofland, H. W. C., van Loey, N. E. E., & Zijlstra, E. E. (2025). Dutch post-graduate training in Global Health and Tropical Medicine: A qualitative study on graduates’ perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 25, 663. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-07126-6