Main content

The 2023 WHO (World Health Organisation) guideline on acute malnutrition sheds new light on infants less than six months of age.[1] The 2013 version focussed on outpatient, community-based treatment for children from 6 to 59 months [2], leaving many infants less than six months old undetected and untreated. [3] There is growing evidence that malnutrition can start as early as in utero or shortly after birth, so young infants should be included in global efforts to reduce maternal and child malnutrition. [4] A recent Lancet series revealed that more than a quarter of babies worldwide are born preterm or at low birth weight. (5) Besides, episodes of being underweight or wasted are frequent between birth and six months of age. (6) Early malnutrition increases risk of mortality [7] and impairment of growth and development (8) as well as chronic diseases later in life. [9] In this paper, we present perspectives of stakeholders from various parts of the world on care for malnutrition in infants less than six months of age.

Radical change for infants less than six months

Defined as “infants less than six months of age at risk of poor growth and development”, the new WHO guideline broadens the term “malnutrition”, proposing a set of criteria from infants with low birth weight to poor growth in the first six months, that should be adapted to the local context. [1] Also, the treatment recommendations are rather generic, formulated as guiding principles for care. The most radical change in the guideline is the focus on primary level, outpatient care, with referral to hospitals only for complications. The emphasis is on early detection and proper assessment, in order to provide timely support. Breastfeeding assessment and counselling, maternal mental support, and management of basic health problems are key elements of care. Milk supplements should be prescribed cautiously to not interfere with breastfeeding, respecting hygiene standards.

The mami approach

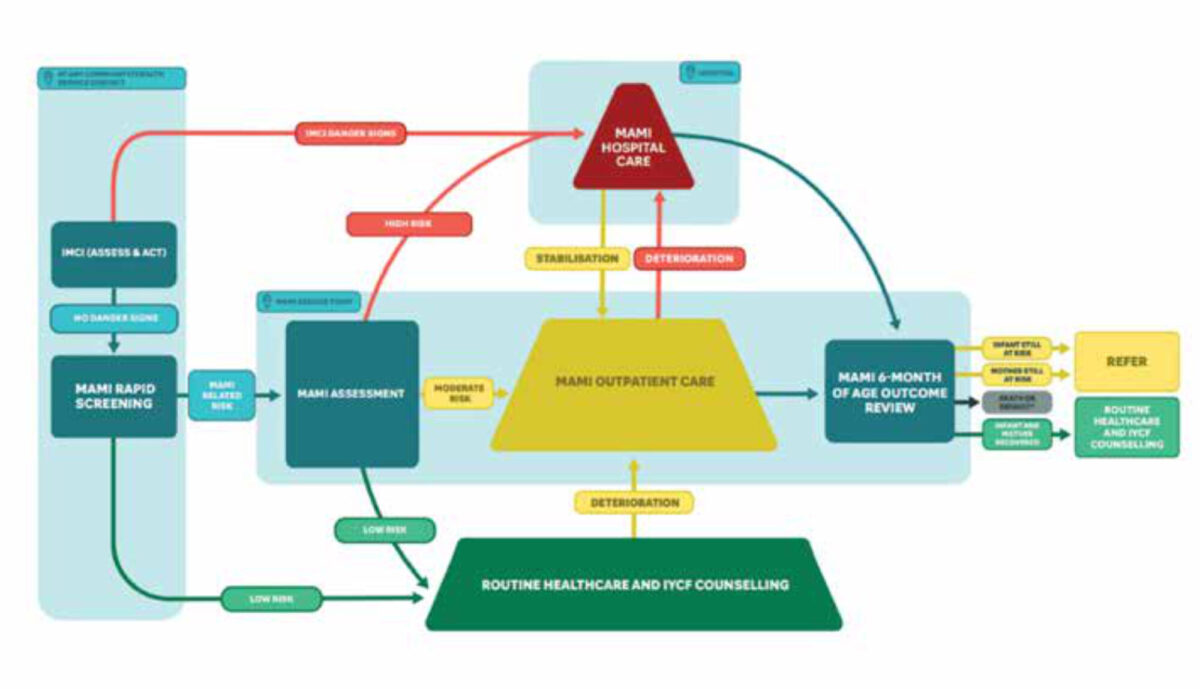

In anticipation of this guideline, a global network of researchers and policy makers developed a care pathway for the management of small and nutritionally at-risk infants under six months and their mothers (MAMI) [10] (Figure 1). MAMI uses similar case definition and care principles as the WHO guideline, and a package of guides and counselling cards has been developed and updated in 2021.[11] Pilot testing in Ethiopia and Bangladesh showed early recovery of infants, prevention of severe malnutrition, and satisfaction by health workers and programme managers. [12] Earlier qualitative research revealed health workers’ and caregivers’ preference for outpatient care for this age group. [13] MAMI operational research and learnings have directly fed into the new WHO guideline. [14]

Stakeholder consultation

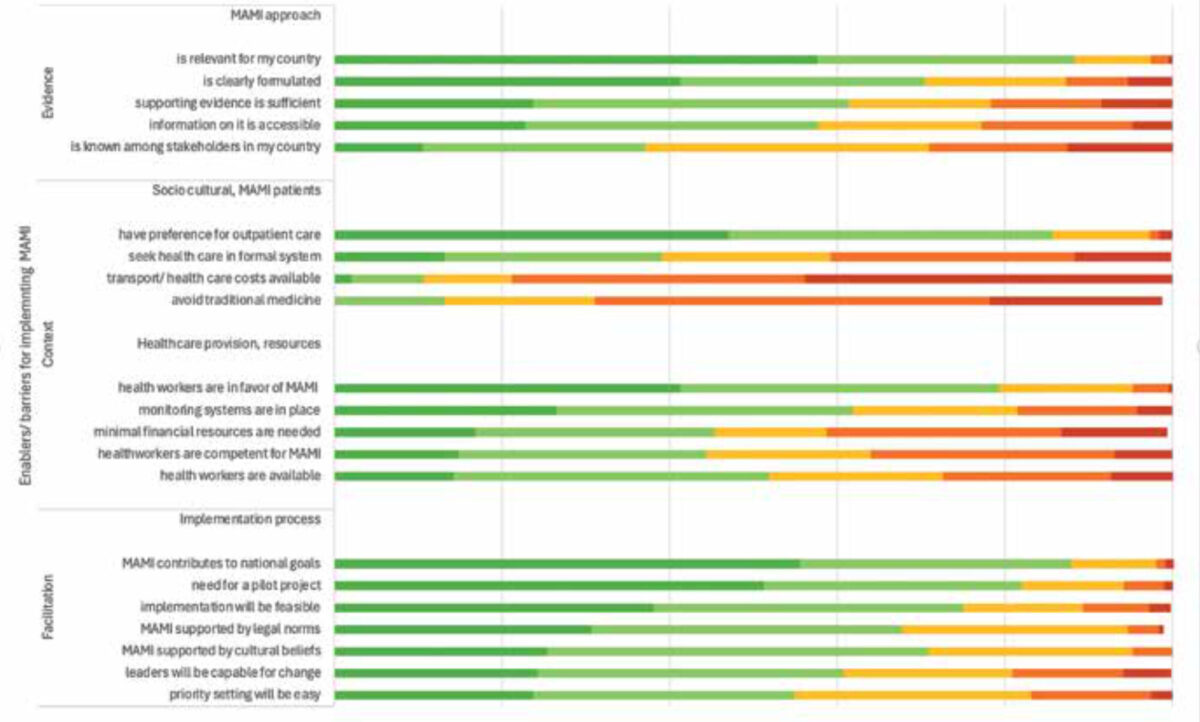

We conducted an early-stage formative implementation study aiming to investigate stakeholders’ views on the feasibility of implementing the MAMI approach (for full report see [15]), which is relevant for the new WHO guideline. We used an online survey and semi-structured interviews with country-level stakeholders in nutrition and child health. The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) theoretical framework for implementation science was used to group barriers and enablers for implementation, in line with its three aspects [16]:

- “Evidence” refers to scientific research, data sources and evidence underpinning the guideline;

- “Context” refers to the socio-cultural setting and the health system in which implementation takes place;

- “Facilitation” is defined as the dynamics or actors supporting implementation.

Country-level stakeholders in nutrition and child health were invited to participate in an online survey of 12 multiple choice closed questions based on the three PARIHS elements. The invitation was spread through the MAMI Global Network newsletter and other nutrition and child health online platforms. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposely selected subset of survey respondents, together with more in-depth discussions of the perceived barriers and enablers.

Results

189 stakeholders participated in the online survey and 14 remote interviews were conducted. See Table 1 for characteristics of the participants. Figure 2 shows barriers and enablers grouped in line with the three PARIHS dimensions.

Table 1. Participant characteristics of survey and interviews

| Surveys N (%) | Interviews N | |

|---|---|---|

| WHO geographical regions (no countries) | ||

| Region of the Americas (6) | 14 (7) | 2 |

| African region-West (11) | 49 (26) | 4 |

| African region- East/ central (12) | 48 (25) | 3 |

| South-East Asia region (5) | 35 (19) | 4 |

| Western Pacific region (3) | 10 (5) | 1 |

| Eastern Mediteranian Region (5) | 20 (11) | 0 |

| Global | 13 (7) | 0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 84 (44) | 8 |

| Female | 105 (56) | 6 |

| Age | ||

| < 30 years | 19 (10) | 1 |

| 31-40 years | 62 (33) | 3 |

| 41-50 years | 65 (34) | 5 |

| 51-60 years | 28 (15) | 2 |

| >60 years | 15 (8) | 3 |

| Educational level | ||

| Undergraduate | 32 (17) | 1 |

| Masters | 111 (59) | 6 |

| Post-master | 46 (24) | 7 |

| Type of organisation | ||

| NGO | 88 (47) | 4 |

| Government | 58 (31) | 2 |

| University | 33 (17) | 3 |

| UN agency | 26 (14) | 4 |

| Private | 18 (10) | 1 |

| Type of stakeholder | ||

| Program manager | 112 (59) | 7 |

| Clinician/academic | 63 (33) | 4 |

| Policy maker | 14 (7) | 3 |

| Years of experience | ||

| <2 years | 25 (13) | 0 |

| 2-5 years | 53 (28) | 0 |

| 5-10 years | 47 (25) | 10 |

| >10 years | 64 (33) | 4 |

Evidence

The MAMI approach was largely unknown in most countries, but 142 (75%) of stakeholders considered it feasible and 166 (88%) relevant.

“So they (at-risk infants) fall through the cracks of the system; they are missed most of the time.” [12]

Participants emphasised that more evidence is needed on anthropometric screening methods for infants less than six months old. This method should be simple for usage at community level.

“..but we are not able to identify at the correct time. So, because of that, also we are losing many children that we could have saved.” [18]

Context

Contextual barriers were expected on access to care, with strong health care seeking in the informal sector mentioned by 163 (86%) of respondents and a lack of means and transport by 149 (79%). The strong community influence on care for young infants was seen as a barrier and potential enabler for implementation.

“It needs a whole tribe to raise a child…” [13]

Many stakeholders mentioned primary care workers’ lack of time (91, 48%) and competence (106, 56%) to provide MAMI care, especially breastfeeding counselling, although they would likely have a positive attitude towards the approach.

“It’s not just how well trained they are, but also how passionate they are about it…., I feel that it requires a passion.” [17]

Community health workers could play a key role in delivering care tailored to local community needs.

“… and they (community health workers) are actually the change maker at community level.” [110]

Facilitation

There were mainly enablers in the PARIHS facilitation dimension with 166 (88%) of survey respondents seeing MAMI as contributing to country goals and 155 (82%) who would wish a pilot project. Integration of the MAMI approach within already existing maternal and child health programmes, was brought up as an enabler to the implementation process by most interview respondents.

“We have plenty of opportunities… Almost all children come for their vaccination, during which time the child can be validly screened.” [13]

NGOs were ranked first as actors enabling the implementation, notably by piloting MAMI

“some NGOs in community health are strong in malnutrition,…some of them are able to inflame the governmental to accept (the change).” [14]

Lessons learned for who guideline implementation:

In this formative study, stakeholders in nutrition and child health from 42 countries expressed an urgent need for a shift in nutritional care for infants less than six months of age. The following insights can inform implementation of the newly published WHO guideline.

Evidence

Within the PARIHS dimension of “evidence”, stakeholders highlighted the need for more scientific data on the anthropometric method for use in the assessment of infants less than six months. The new WHO guideline proposes weight for age Z-score (WAZ) and/or mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), which have been shown to be more reliable than weight for length z-score in detecting infants at risk. [17] WAZ is already widely used for growth monitoring, which could enable implementation. Generally, WHO recommendations for detection and treatment of at-risk or malnourished infants less than six months are based on weak evidence. Operational and implementation research is needed to strengthen the evidence. The MAMI package and its tools can support these efforts.

Context

Most implementation barriers in our study were placed in the “context” dimension of PARIHS, concerning social-cultural as well as health provision factors. Socio-cultural factors, such as knowledge and beliefs around childhood and new-born illnesses, as well as care costs and means of transport are known to highly determine the implementation fidelity or sustainability of nutrition interventions. [18] The new WHO guideline aims to overcome these barriers in two ways. First, shifting the level of care to primary or community care will bring care closer and reduce access barriers. Second, the infant with the mother/caregiver are treated as a pair and “grounded in a family-centred and context-adapted approach”, which will encourage community engagement in health care seeking.

Our survey respondents were concerned about the increased workload for primary and community health care workers. With these new elements in the WHO guideline, there is a pressing need for training and capacity building. Earlier research from Ethiopia showed that by training primary care staff and involving community stakeholders, service availability was improved and patient trust was increased.[19] An important aspect in training is reinforcing health workers’ role in breastfeeding counselling, which is highly underestimated in many countries. [20]

Facilitation

Finally, within the “facilitation” dimension, our study emphasised the importance of integrating the MAMI approach into existing structures and making use of local resources. A review assessing the integration of nutrition related programmes showed improved outcomes of the primary programme when well-integrated. [21] The WHO guideline states that a strong focus on continuity of care and inter-linkages with existing services is essential for the effectiveness and feasibility of the approach. This means active communication between services like antenatal/postnatal care, sexual and reproductive care, and other services for infants less than six months, such as vaccination or growth monitoring.

Conclusion

The new WHO guideline for infants less than six months at risk for poor growth and development, can potentially bridge gaps in detection and care for this vulnerable group. The approach, which is similar to MAMI, is not a one-size-fits-all guideline, and stakeholders will need to continuously be involved in local evidence generation and its adaptation to the context.

References

- WHO. The WHO Guideline on the Prevention and Management of Wasting and Nutritional Oedema (Acute Malnutrition). 2023.

- WHO. Guideline: updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children: World Health Organization, 2013.

- Kerac M, Mwangome M, McGrath M, Haider R, Berkley JA. Management of acute malnutrition in infants aged under 6 months (MAMI): Current issues and future directions in policy and research. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 2015; 36(1).

- Victora CG, Christian P, Vidaletti LP, Gatica-Domínguez G, Menon P, Black RE. Revisiting maternal and child undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries: variable progress towards an unfinished agenda. The Lancet 2021; 397(10282): 1388-99.

- Lawn JE, Ohuma EO, Bradley E, et al. Small babies, big risks: global estimates of prevalence and mortality for vulnerable newborns to accelerate change and improve counting. Lancet 2023; 401(10389): 1707-19.

- Kerac M, Frison S, Connell N, Page B, McGrath M. Informing the management of acute malnutrition in infants aged under 6 months (MAMI): risk factor analysis using nationally-representative demographic & health survey secondary data. PeerJ 2019; 6: e5848.

- Grijalva-Eternod CS, Kerac M, McGrath M, et al. Admission profile and discharge outcomes for infants aged less than 6 months admitted to inpatient therapeutic care in 10 countries. A secondary data analysis. Matern Child Nutr 2017; 13(3).

- Walker SP, Wachs TD, Gardner JM, et al. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. The lancet 2007; 369(9556): 145-57.

- Grey K, Gonzales GB, Abera M, et al. Severe malnutrition or famine exposure in childhood and cardiometabolic non-communicable disease later in life: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 6(3).

- McGrath M. Management of small and nutritionally at risk infants under six months and their mothers (MAMI). 2021 (accessed 20 March 2022).

- Network MG. MAMI Care Pathway Package. https://www.ennonline.net/attachments/4004/MAMI-Care-Pathway-Package-Document-_07June2021.pdf, 2021.

- Butler S, Connell N, Barthorp H. C-MAMI tool evaluation: Learnings from Bangladesh and Ethiopia. Field Exchange 2018; 58(62)

- van Immerzeel TD, Camara MD, Deme Ly I, de Jong RJ. Inpatient and outpatient treatment for acute malnutrition in infants under 6 months; a qualitative study from Senegal. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19(1): 69.

- MAMIGlobalNetwork. MAMI Global Network Strategy 2021-2025, 2021.

- van Immerzeel TD, Diagne M, Deme/Ly I, et al. Implementing a Care Pathway for small and nutritionally at-risk infants under six months of age: A multi-country stakeholder consultation. Matern Child Nutr 2022; 19(1): e13455.

- Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. BMJ Quality & Safety 1998; 7(3): 149-58.

- Hoehn C, Lelijveld N, Mwangome M, Berkley JA, McGrath M, Kerac M. Anthropometric Criteria for Identifying Infants Under 6 Months of Age at Risk of Morbidity and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2021; 15: 11795565211049904.

- Sarma H, D’Este C, Ahmed T, Bossert TJ, Banwell C. Developing a conceptual framework for implementation science to evaluate a nutrition intervention scaled-up in a real-world setting. Public Health Nutr 2021; 24(S1): s7-s22.

- Miller NP, Bagheri Ardestani F, Wong H, et al. Barriers to the utilization of community-based child and newborn health services in Ethiopia: a scoping review. Health Policy and Planning 2021.

- Kinshella M-LW, Prasad S, Hiwa T, et al. Barriers and facilitators for early and exclusive breastfeeding in health facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Global health research and policy 2021; 6(1): 1-11.

- Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Integrating nutrition into health systems: What the evidence advocates. Matern Child Nutr 2019; 15 Suppl 1: e12738.