Main content

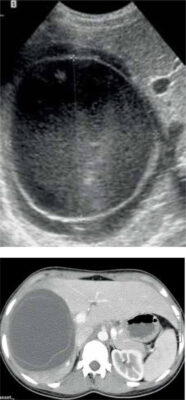

Noma (also known as cancrum oris) is a quickly spreading orofacial gan-grene affecting malnour-ished children, nowadays mainly observed in tropical countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, but in earlier ages common all over the world.[1,2] The aetiology of noma is multifactorial. A precondition is malnutrition, often related to pov-erty, combined with concomitant diseases such as measles, malaria and HIV.

Epidemiology

The global incidence is not known. Estimates range from 30,000 to 140,000 individuals.[3,4] Children with the age of 2 to 7 years are most vulner-able to developing this non-contagious condition, which is most commonly seen in Sub-Saharan Africa. Without antibiotic treatment, the mortality of noma is around 85%. With adequate treatment (amoxillin and metronida-zole, hydration and nutritional sup-port, and treatment of concomitant diseases and deficiencies) the mortal-ity rate is reduced to around 15%.[5]

Prevention, preceding clinical signs, acute noma in stages and microbiology

Noma is often preceded by a small intraoral ulcer or acute necrotizing gin-givitis (ANG), a common finding in poor areas in Africa.[6] A practical approach for prevention of noma is to identify in endemic regions the local com-munities where ANG is prevalent. An awareness programme among the local population and health workers, with introduction of efficient oral hygiene practice and nutritional support, are the ingredients for a preventive strategy.[7]

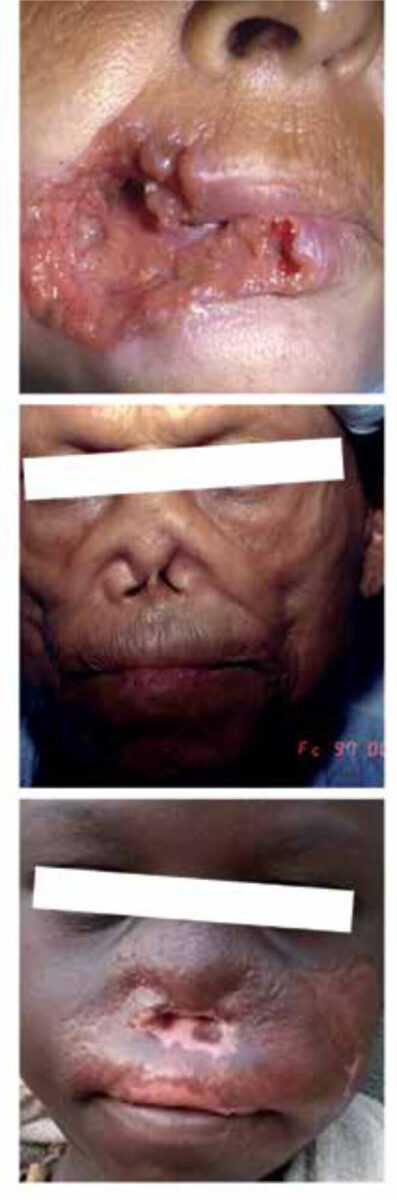

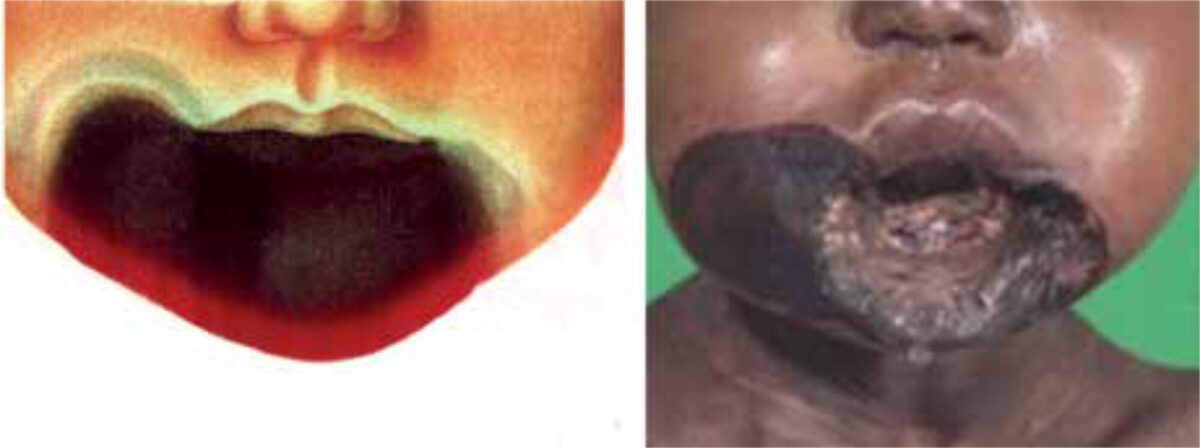

The first signs of noma are facial oedema and an almost pathognomonic halitosis. Within a few days, the second phase starts: a rapidly spread-ing necrotizing infection into the intraoral mucosa, the facial muscles, the skin and the facial skeleton. In this phase, hypersalivation is a fre-quent symptom. This explains why, in earlier centuries, in many countries in Europe, noma was called ‘water cancer’.[2] Most noma patients die during this septic second phase. In those who survive, one observes that the gangrene becomes demarcated; this is called the third phase. In this phase, the necrotic tissue is eliminated by the body by suppuration, slough-ing and sequestration, followed by secondary wound healing (granula-tion, contraction of tissue, secondary reepithelialisation and remucosalisa-tion), often a process of many months.

Microbiological considerations about noma have changed over time. One century ago, experts expected to find a specific ‘bacillus nomae’. Halfway through the 20th century, bacteria such as Borrelia vincentii and Fusiformis fusiformis were considered to be involved in the infectious process leading to gangrene. Nowadays, noma is seen as a multifactorial opportunistic infec-tion developing in a relatively normal oral flora in patients with an impaired immune system, caused by factors such as malnutrition and concomitant dis-eases like measles, HIV and malaria.[8]

Noma sequelae and reconstructive surgery

Depending the extent of the necrosis, the sequelae of noma present a kaleido-scopic variety of facial deformities, often with debilitated function of eating (tris-mus) and speech, and leakage of saliva as well as social ostracization. Often it leads to further facial deformities due to growth disturbances of the facial skeleton at a later age. Reconstructive surgery in order to treat trismus and improve the aspect of deformed noma faces is only provided by a few Western NGOs in the ‘noma belt’ of the world, the Sub-Saharan countries, (rarely also in European hospitals), and reaches only a few of the estimated 210,000 noma survivors in the world.[4] Because of the variety of sequelae, noma recon-structive surgery is one of the most challenging parts of reconstructive surgery. It requires thorough experi-ence with all reconstructive operative techniques, an imaginative mind, and high technical skill.[5,9] Also, intuba-tion of a noma patient sometimes is a difficult procedure, and therefore a challenge for anaesthetists.[10] This should be performed only in the setting of tertiary health care. The surgi-cal adage to keep these procedures ‘sim-ple, safe and satisfactory’ is valuable. Nevertheless, the postoperative compli-cation rate in noma patients, treated by expert teams, is high.[11] On the other side, the social impact of successful sur-gical rehabilitation is rewarding, leading to better chances for education, employ-ment and even marriage after surgery.[12]

Differential diagnosis

Though Sterling V. Mead, author of Oral surgery (1946), commented that concerning the differential diagnosis of noma “there is nothing else like it“[5], there may be patients who present with facial deformities that are very suggestive for noma as cause, but whose mutilated faces have another aetiology like leishmaniasis, leprosy, squamous cell carcinoma, yaws, gangosa, syphilis and trauma.[4,5]

A neglected ‘neglected tropi-cal disease’ and a matter of human rights

Noma is a condition that can be pre-vented completely by securing food security for the poorest inhabitants worldwide.[1] The fact that the condition still exists on a large scale is a real dis-grace to mankind. A prominent feature of noma is omnipresent neglect by medical science, governments of coun-tries where the condition is prevalent, and the World Health Organization. Noma does not appear on the list of seventeen neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), despite data indicating that the global burden of noma, expressed in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), is estimated at 1.1 million.[13] Actions by Jean Ziegler, professor in sociology and member of the Advisory Committee of the United Nations Human Rights Council (during 2000-2008), led to the adoption of Resolution 19/7: the right to food, with children affected by noma as evidence of a violation of this right.[14]

Noma is an old companion of man-kind and will continue to be so, unless mankind takes its humani-tarian responsibility seriously.

References

- Marck KW. A history of noma, the “face of poverty”. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Apr 15;111(5):1702-7. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000055445.84307.3C

- Marck, KW. Noma, the face of poverty. Hannover: MIT-Verlag GmbH; 2003

- Fieger A, Marck KW, Busch R, et al. An estimation of the incidence of noma in north-west Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2003 May;8(5):402-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01036.x

- Srour ML, Marck KW, Baratti-Mayer D. Noma: overview of a neglected disease and human rights violation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017 Feb 8;96(2):268-74. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0718

- Tempest MN. Cancrum oris. Br J Surg. 1966 Nov;53(11):949-69. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800531109

- Idigbe EO, Enwonwu CO, Falkler WA, et al. Living conditions of children at risk for noma: Nigerian experience. Oral Dis. 1999 Apr;5(2):156-62. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00082.x

- Baratti-Mayer D, Gayet-Ageron A, Cionca N, et al. Acute necrotising gingivitis in young children from villages with and without noma in Niger and its association with sociodemographic factors, nutritional status and oral hygiene practices: results of a population-based survey. BMJ Glob Health. 2017 Aug 30;2(3):2000253. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-00025

- Baratti-Mayer D, Gayet-Ageron A, Hugonnet S, et al. Risk factors for noma disease: a 6-year, prospective, matched case-control study in Niger. Lancet Glob Health. 2013 Aug;1(2):e87-e96. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70015-9

- Bos K, Marck K. The surgical treatment of noma. Alphen aan den Rijn: Belvédère/Medidact; 2006. 125 р.

- Coupe MH, Johnson D, Seigne P, et al. Special article: airway management in reconstructive surgery for noma (cancrum oris). Anesth Analg. 2013 Jul;117(1):211-8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182908e6f. Epub 2013 Jun 3

- Bouman MA, Marck KW, Griep JEM, et al. Early outcome of noma surgery, J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010 Dec;63(12):2052-6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.02.012

- Lafferty NE, Changing the face of Africa [master’s thesis]. Liverpool: School of Tropical Medicine; 2012

- Hotez PJ, Alvarado M, Basáñez MG, et al. The global burden of disease study 2010: interpretation and implications for the neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014 Jul 24;8(7):e2865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865

- Srour ML, Marck KW, Baratti-Mayer D. Noma: neglected, forgotten and a human rights issue. Int Health. 2015 May;7(3):149-50. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv0OI