Main content

Oral diseases present a major public health challenge worldwide.[1] Many people across the globe still suffer unnecessarily from the pain and discomfort associated with oral diseases. The two main oral diseases – dental caries and periodontal dis-ease – are highly prevalent, despite being largely preventable. They have significant impact on individuals, health systems and the wider soci-ety. Pain, sleepless nights, malnu-trition, low quality of life, school absenteeism and work productivity loss are all common effects of oral diseases. Oral treatment is also very costly to both individuals and healthcare systems.

Although oral health has sig-nificantly improved in high-income countries in recent decades, levels of oral disease appear to be increas-ing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) – in conjunction with economic development and consequent changes in nutrition and lifestyle, for example due to the higher availability of sugars. A second concern in LMICs is the persistent nature of oral health inequalities. People from lower socioeconomic positions and mar-ginalized groups are experiencing disproportionately higher levels of oral disease.[2] There has been limited success thus far in generat-ing political interest and action to address these oral health problems. Oral health is still characterized by neglect and low prioritization by governments and health systems, particularly in LMICs.[3,4]

Oral health and general health – common risk factors and determinants

Oral health is an integral element of general health. Poor oral health can adversely affect general health condi-tions and vice versa, through shared inflammatory pathways. For example, periodontal disease has been associated with a higher risk of developing dia-betes, cardiovascular disease, preterm birth and dementia in adults [5], while severe dental caries has been associated with stunted growth in children.[6]

Most oral diseases share common risk factors with other non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as smoking, alco-hol use and sugar consumption. These behaviours are influenced by broader social determinants [7]: the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. In LMICs, determinants such as poverty, poor living conditions, low education, unemployment, inad-equate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and poor access to healthcare all contribute to a higher risk of oral diseases in the population. The unequal distribution of these determinants across the world accounts for the persist-ing inequalities in (oral) disease burden.

The burden of oral diseases

Dental caries

Dental caries (tooth decay) is the most widespread human disease.[8] It is a multifactorial disease caused by the interaction between bacteria in dental plaque (biofilm), sugars and the tooth surface. Bacteria in dental plaque pro-duce acids when metabolizing sugars, which dissolve the tooth enamel and causes cavities.[9] Fluorides have been used since the 1940s to prevent tooth decay. There is overwhelming evidence that long-term exposure to low concen-trations of fluorides is associated with clear reductions in dental caries.[10] Hence, key measures to prevent dental caries include twice daily tooth brush-ing with fluoride toothpaste as soon as the first primary teeth erupt (around 6 months of age) and reducing the frequency of consuming sugary foods and drinks. It is important that these behaviours are introduced and shaped during early life, setting children on a path to good oral health in later life.

Most dental caries remain untreated, which can lead to infection of the pulp, abscesses, and subsequent pain and impacts on physical and psychological well-being. The Global Burden of Disease study revealed that untreated dental caries in the permanent dentition is the single most prevalent global condi-tion out of 291 diseases studied.[8] The age-standardized prevalence was 34.1% in 2015, affecting 2.5 billion people worldwide. The highest prevalence of dental caries is found in middle-income countries (MICs), particularly in South and Southeast Asia and South America.[11] In low-income countries (LICs), dental caries levels are gener-ally lower but almost all of the caries are left untreated (98%), indicating weak oral healthcare systems.[11]

Periodontal disease

Periodontal disease (gum disease) is an inflammatory condition of the periodon-tium, the tissues supporting the teeth.[12] Periodontitis initially presents as gingi-vitis, a reversible chronic inflammation of the gums. This can progress to (severe) periodontitis with irreversible tissue destruction, including bone loss surrounding the teeth. Periodontal disease is caused by specific microbes in the dental plaque due to poor oral hygiene. Other risk factors include stress, smoking, excessive alcohol use, low fruit and vegetable consumption, genetic factors and diabetes mellitus.[12]

According to the Global Burden of Disease study, severe periodontitis is the sixth most common disease worldwide, with a global prevalence of 10%.[8] In 2015, it was estimated that 538 million people were affected by the disease. The prevalence is highest in South America and West Africa. Periodontitis is the main cause of tooth loss in adults, and has a negative impact on chewing abil-ity, self-esteem, social functioning and employment opportunity.[1,11,12] Globally, thirty percent of people between the age of 65 and 74 years have lost all their teeth, mainly due to periodon-tal disease.[11] A total of 276 million people worldwide are edentulous.[8]

Oral cancer

Oral cancer includes cancer of the lips, tongue, gum, floor of the mouth, pal-ate, cheek mucosa and vestibule of the mouth. Tobacco use, especially when combined with alcohol consumption, is a major risk factor of oral cancer.[1,11] In Asia, chewing tobacco with carci-nogenic substances from betel nut poses an additional risk. Men are more commonly affected than women, as are people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.[11] Oral cancers gener-ally present as an ulcer that does not heal, often preceded by precancerous lesions shown as red of white patches.

Oral cancer is among the 15 most common cancers, with an estimated 500,000 new cases and 180,000 deaths per year.[1,8] Oral cancer rates vary greatly depending on the region; rates are highest in South and Southeast Asia, but the burden is also high in France, Eastern Europe and parts of Africa.[12] Kaposi’s sarcoma in particu-lar is more prevalent in LMICs, as it is a relatively common condition in people with HIV/AIDS. Over 35% of people with AIDS are affected.[13] The survival rate for oral cancers is among the lowest of all cancers; the mean five-year-survival is only 50%.[14] Late detection of oral cancers is one of the main reasons for the low survival rate.

Other oral diseases

Other oral diseases that affect the soft and hard tissues of the mouth include craniofacial disorders, congenital anomalies, trauma, dental erosion, and various infections. One neglected oral disease that is specifically observed in the least developed countries around the world is noma. Noma is a rapidly progressive infection with severe gan-grenous destruction of the tissues of the mouth and face, affecting mainly two- to six-year-old children in Sub-Saharan Africa. Main causes are malnutrition and poor sanitation. It is estimated that 140,000 cases of noma are reported each year and, if left untreated, 70% to 90% of those affected die.[11]

Symptoms in the mouth resulting from systemic and/or infectious diseases

The mouth is a mirror of the body. Examination of symptoms in the mouth can reveal the presence of certain underlying diseases, including infec-tious diseases such as HIV, nutritional deficiencies or eating disorders. There are over 30 million people across the globe with HIV infections. Over 50% of those affected with HIV develop oral manifestations at an early stage, such as bacterial, fungal or viral infections – often of the herpes family – but warts, lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma and hairy leukoplakia are also observed.[15] Patients with HIV also have an increased suscep-tibility to periodontal breakdown. Other sexually transmitted diseases, such as syphilis and gonorrhoea, frequently pro-duce lesions on the oral mucosa as they affect mucous membranes.[16] Lesions associated with syphilis are chancre of the oral mucosa (primary syphilis), or oral ulcers, glistening patch or mucous patch, and an ulcerated plaque covered by a grey-white necrotic membrane (secondary syphilis).[16] Patients with gonorrhoea may present with painful non-specific pharyngitis. Oral mani-festations could also be indicative of nutritional deficiencies.[16] Patients with anaemia for example have a higher prevalence of atrophic glossitis, angular cheilitis, burning sensation of the oral mucosa, dry mouth and oral lichen pla-nus.[17] The eating disorder bulimia can lead to erosion of the teeth. (Oral) health professionals must be aware of the oral manifestations of underlying diseases, as they can play an important role in the early detection and referral of patients.[18]

Strategies to promote oral health in LMICS

Ensuring access to basic oral healthcare

Historically, oral health promotion follows an ‘interventionist’ approach by providing curative and preventive care to individual patients in clinical dental settings. This approach is very costly in terms of financial and human resources, and therefore unaffordable for many LMICs – particularly in light of the high oral disease burden. The scarcity of resources, combined with the competing healthcare demands in LMICs, makes investment in oral healthcare very limited.[4] Another problem is the low workforce numbers, which is reflected in the global density of dentists; most HICs have a density of one dentist per 1,000 to 3,000 people in the population (the “ideal ratio” accord-ing to Western norms), while this ratio is one to 100,000 to more than 200,000 people in most African countries.[19] Another challenge is that dentists tend to be concentrated in affluent urban areas, leaving disadvantaged popula-tions in rural areas underserved.[11] As a result, many people in LMICS must rely on the care of illegal practi-tioners who lack professional training and/or the necessary equipment.

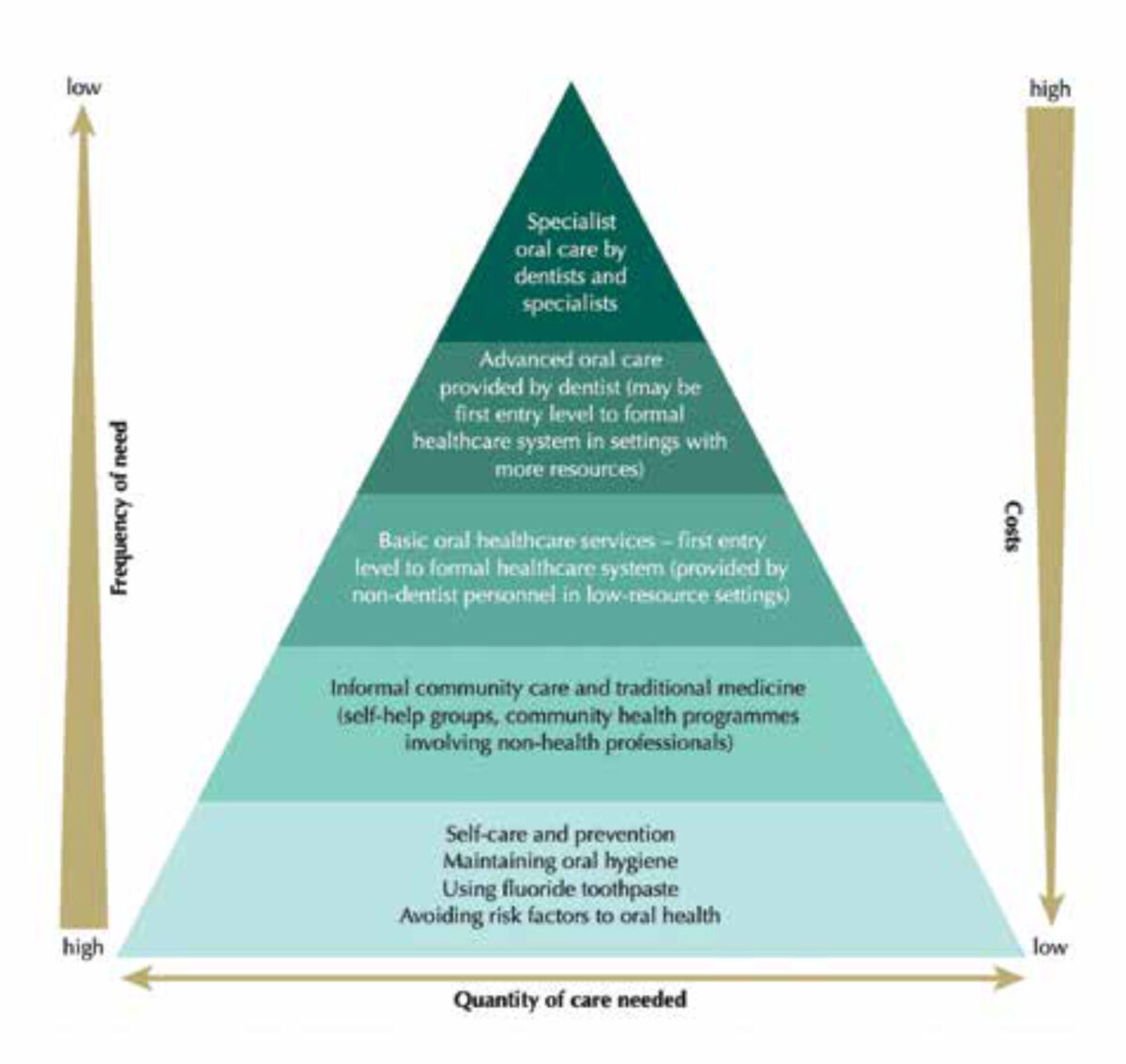

A fundamentally different approach is therefore needed. Access to basic oral healthcare should be integrated into the concept of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). UHC is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a system in which “all people have access to primary health services and do not suffer financial hardship for paying them”.[20] The Basic Package of Oral Care (Figure 1) aims to help countries to direct scarce resources for oral health to address essential and common needs.[21] Ideally, the initial focus is on cost-effective and evidence-based interventions to promote self-care and prevention, including ensuring the availability of fluoride toothpaste. A minimum requirement is to cover basic emergency oral care and pain relief (e.g. tooth extractions) at the entry levels of healthcare systems (provided by non-dentist personnel in low-resource settings). More costly curative and specialist care can be added and would be available at higher second-ary levels of the healthcare system.

Integrating oral health into health policies

The close bi-directional relationship between oral and general health, and the shared risk factors and determi-nants provide a strong basis for the integration of oral health into general health promoting policies. Important steps are to increase inclusiveness and recognition of oral health in existing policies and programmes, and to align efforts to promote oral health with international frameworks such as the WHO global action plan on NCDs and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[22] The global action plan on NCDs includes a road map of (upstream) policy actions to achieve targets to reduce the burden of NCDs by 2025. Many policies target modifiable risk factors such as tobacco use and sugar consumption and underlying social determinants, and are therefore also beneficial to oral health. The SDGs also provide opportunities for more inclusion and better prioritization of oral health, particularly under SDG 3, “healthy lives and well-being for all”. This global momentum for NCDs and global public health and development provides a window of opportunity to initiate prog-ress to tackle the burden of oral disease across the globe, particularly in LMICs.

References

- Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, Benzian H, Allison P, Watt RG. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019; 394: 249-60.

- Watt RG, Listl S, Peres M, Heilmann A. Social inequalities in oral health: from evidence to action. International Centre for Oral Health Inequalities Research & Policy (ICOHIRP), University College London, 2015. Available at: http://www.icohirp.com (Accessed 25th February 2022).

- Benzian H, Hobdell M, Holmgren C, Yee R, Monse B, Barnard JT, van Palenstein Helderman W. Political priority of global oral health: an analysis of reasons for international neglect. Int Dent J. 2011; 61: 124-30.

- Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, Macpherson LMD, Venturelli R, Listl S, Weyant RJ, Mathur MR, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Celeste RK, Peres MA, Kearns C, Benzian H. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet. 2019; 394: 261-72.

- Otomo-Corgel J, Pucher J, Rethman M, Reynolds M. State of the science: chronic periodontitis and systemic health. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2012; 12: 20-8.

- Dimaisip-Nabuab J, Duijster D, Benzian H, Heinrich-Weltzien R, Homsavath A, Monse B, Sithan H, Stauf N, Susilawati S, Kromeyer-Hauschild K. Nutritional status, dental caries and tooth eruption in children: a longitudinal study in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR. BMC Pediatr. 2018; 18: 300.

- Watt RG, Sheiham A. Integrating the common risk factor approach into a social determinants framework. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012; 40: 289-96.

- Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, Murray CJL, Marcenes W; GBD 2015 Oral Health Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence, Incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Oral Conditions for 195 Countries, 1990-2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. J Dent Res. 2017; 96: 380-7.

- Fejerskov O, Kidd E. Dental caries: The disease and its clinical management. 3rd ed. West Sussex John: Wiley & Sons, ltd; 2015.

- Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, Marinho VCC, Jeroncic A. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019; 3: CD007868.

- Benzian H, Williams D, eds. The challenge of oral diseases—a call for global action. The Oral Health Atlas, 2nd edn. Geneva: Fédération Dentaire Internationale World Dental Federation, 2015. Available at: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/oral-health-atlas (Accessed 25th February 2022).

- Berglundh T, Giannobile WV, Sanz M, Lang NP. Lindhe’s Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 7th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2021.

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, Martin J, Bower M, Whitby D. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019; 5: 9.

- Cancer statistics 2018. GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr (Accessed 25th February 2022).

- Johnson NW. The mouth in HIV/AIDS: markers of disease status and management challenges for the dental profession. Aust Dent J. 2010; 55:85-102.

- Bruce AJ, Rogers RS 3rd. Oral manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2004; 22: 520-7.

- Wu YC, Wang YP, Chang JY, Cheng SJ, Chen HM, Sun A. Oral manifestations and blood profile in patients with iron deficiency anemia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014; 113: 83-7.

- Lo Russo L, Campisi G, Di Fede O, Di Liberto C, Panzarella V, Lo Muzio L. Oral manifestations of eating disorders: a critical review. Oral Dis. 2008; 14: 479-84.

- World Health Organization. The global atlas of the health workforce. Geographic distribution by occupation – dentists. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report: Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

- Frencken JE, Holmgren C, van Palenstein Helderman W. Basic Package of Oral Care (BPOC). Nijmengen, Netherlands: WHO Collaborationg Centre for Oral Health Care Planning and Future Scenarios, University of Nijmegen; 2002.

- WHO Oral Health. Achieving better oral health as part of the universal health coverage and noncommunicable disease agendas towards 2030. Report by the Director-General (EB148/8) 148th Session of the Executive Board, Provisional Agenda Item 6. 23 December 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB148/B148_8-en.pdf (Accessed 25th February 2022).