Main content

A 27-year-old male traveller was admitted to hospital in the Netherlands because of fever and weight loss. He travelled in Africa from north to south during 9 months. He started in Morocco, crossed the Sahara and continued via Nigeria to Zimbabwe. Four months before admission he developed fever, headache and muscle aches; he went to a local laboratory and was found to have a positive blood film for malaria. He was treated with an antimalarial drug after which the fever disappeared. Two months before admission he had an episode of diarrhoea with some blood admixture; there was no fever. He used some tablets from his travel companion (‘against diarrhoea’) and improved. One month before admission he developed fever and muscle aches that continued until admission; later there was also right upper quadrant abdominal pain.

He had been adequately vaccinated for diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis (DTP -booster), typhoid fever, yellow fever, hepatitis A and B and rabies; he used mefloquine as malaria prophylaxis, albeit intermittently.

After returning home, he had persistent intermittent fever, abdominal pain, right shoulder pain and generalized weakness. There was slight non-productive cough. He had lost 5 kg of weight since the start of the fever. He was admitted to hospital.

Physical examination

- Ill looking; not jaundiced; not pale.

- Vital signs: blood pressure 130/85 mm Hg; pulse rate 95/min, regular; respiratory rate 24/min; temperature 39.5 C.

- Head and neck: no abnormalities.

- Lungs: dullness right lower zone; normal breath sounds.

- Heart: apex beat not displaced, not enlarged on percussion; heart sounds S1 S2, no pericardial rub.

- Abdomen: tenderness right upper quadrant, liver enlarged 3 cm, tender, smooth surface, sharp edge.

- Spleen not palpable.

- Extremities: no oedema.

- Skin: in the anterior axillary line at the upper abdomen/lower chest: swelling, redness and tenderness with peau d’orange appearance.

Laboratory results

ESR 60 mm/hr

Hb 8.1 mmol/L

TWC 13.3 x 10⁹/L; differential count: 80% neutrophils

Platelet count: 173 x 10⁹/L

Bilirubin 16 mmol/L

AST 14 U/L

ALT 23 U/L

Alkaline Phosphatase 110 U/L (n< 75)

Questions

- What is the differential diagnosis?

- What diagnostic procedures would you do?

- What is the likely diagnosis?

- What is the preferred treatment?

Answers

- Amoebic liver abscess, pyogenic liver abscess, hepatocellular carcinoma, hydatic cysts; misdiagnosis as cholecystitis or appendicitis occurs.

- Blood cultures (these were negative), rapid diagnostic test and blood film for malaria (negative). Stool examination for parasites and eggs (showed E. histolytica cysts). The chest x-ray showed a raised hemidiaphragm with clear lung fields (the normal breath sounds already suggested that there was no intrapulmonary problem). An ultrasound examination showed four liver abscesses (Figure). A serological test for amoebiasis was positive.

- Amoebic liver abscess with extension to the skin and right hemidiaphragm leading to shoulder pain.

- A tissue amoebicidal drug – tinidazole or metronidazole – followed by a contact amoebicidal drug – paromomycin, clioquinol or diloxanide furoate – for elimination of luminal cysts, even if cysts are not found in the stool examination.

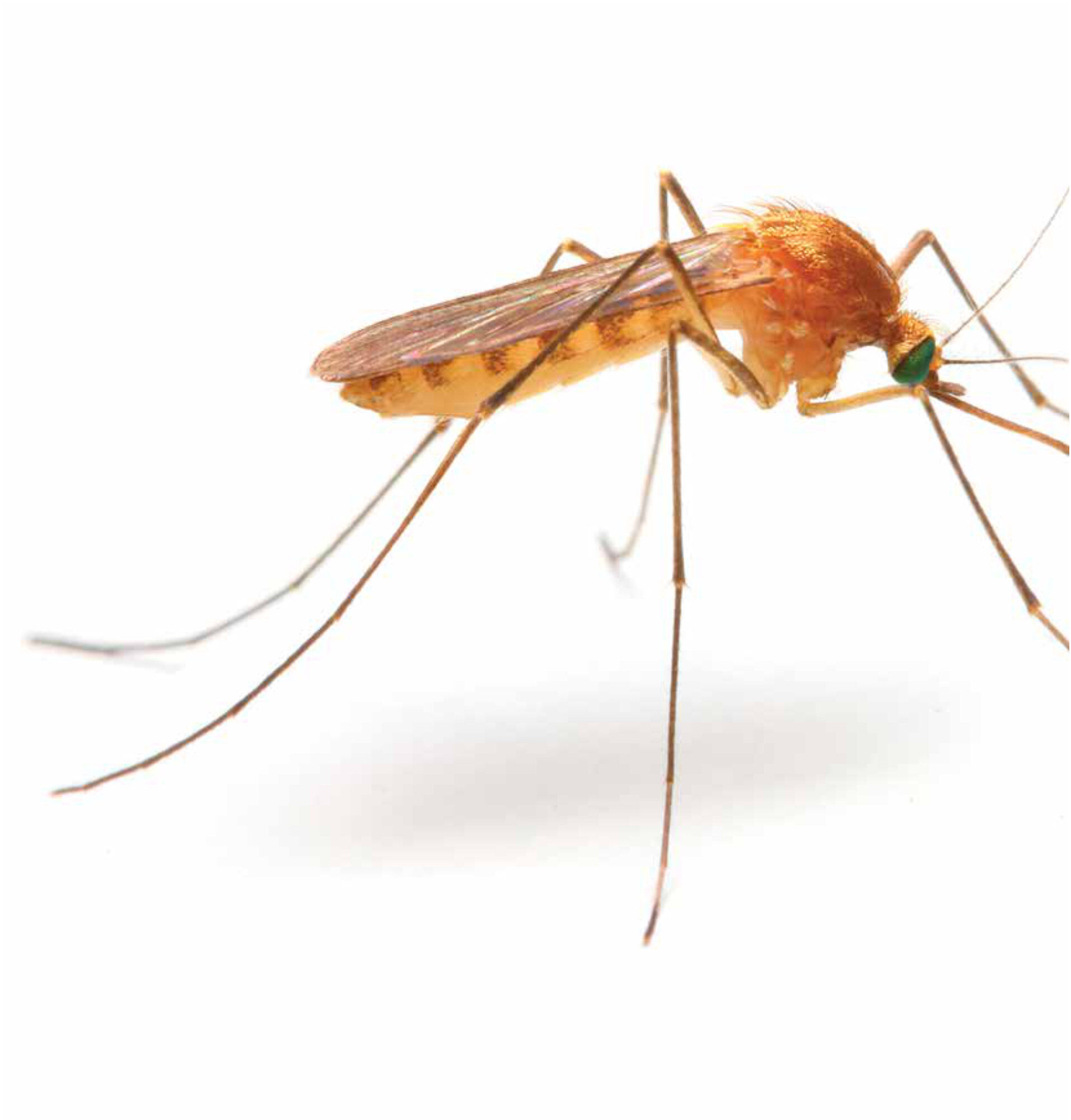

Amoebiasis has a world-wide distribution and it is estimated that 10% of the world population is infected with the causative protozoal agent Entamoeba (E.) histolytica. Most people are asymptomatic (up to 90%). The transmission is faecal-oral and hence it is most common in unhygienic conditions. The most common clinical manifestation is amoebic dysentery characterized by slow onset of bloody and mucoid diarrhoea with abdominal pain; fever is not a prominent feature but sometimes there may be mildly raised temperature.

Only 10% of Entamoeba histolytica parasites are potentially invasive from the gastrointestinal tract. Their microscopic appearance is identical to the non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar, but they can be differentiated by PCR. When invasive (extra-intestinal amoebiasis), the liver becomes infected through the portal vein. A liver abscess may develop that may be single or multiple; large abscess may become confluent. Clinically, the patient has fever, chills, right upper quadrant pain with right or left shoulder pain through irritation of the diaphragm depending on the localization in the liver. Over time, anaemia and weight loss may also occur. A superficial abscess in the right liver lobe may irritate the overlying skin with subsequent infiltration resulting in the ‘peau d’orange’ appearance; this may indicate imminent rupture. From the liver, the abscess may spread into the pleural or pericardial space, or rarely metastasize to e.g. the brain.

Diagnosis requires appropriate exposure in an endemic area, an ultrasound, and a serological test such as the immunofluorescence test; the sensitivity is >95%, one week after onset. There is no need for an aspirate as the parasites are at the edge of the abscess and difficult to target by the needle. In addition, there is a risk of introducing secondary bacterial infection. The white cell count is typically raised as are the liver enzymes, in particular alkaline phosphatase. The stool examination may or may not show E. histolytica cysts. A chest x-ray may show a raised hemidiaphragm with or without pleural effusion.

The treatment response is good and the clinical response (disappearance of fever), normalization of the ESR, white cell count and liver enzymes may be used as parameters for cure. On the ultrasound, the abscesses may disappear or persist for months. Drainage may be indicated in large left lobe abscesses that potentially could perforate to the pericardium, or in severely ill patients with imminent rupture of the abscess, or in case of unresponsiveness to drug treatment. Drainage is also indicated in case of an uncertain diagnosis, in particular with a differential diagnosis of pyogenic abscess where drainage is usually necessary. It is important to eradicate the parasites in the gastrointestinal tract with a contact amoebicidal drug to avoid recurrence of the liver abscess.

References

- Skappak C, Akierman S, Belga S, Novak K, Chadee K, Urbanski SJ, Church D, Beck PL. Invasive amoebiasis: a review of Entamoeba infections highlighted with case reports. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 28: 355-9.

- Stanley SL. Amoebiasis. Lancet 2003; 361: 1025-34.

- Wuerz T, Kane JB, Boggild AK, Krajden S, Keystone JS, Fuksa M, Kain KC, Warren R, Kempston J, Anderson J. A review of amoebic liver abscess for clinicians in a non-endemic setting. Can J Gastroenterol 2012; 26: 729-33.