Main content

Countries in the tropics receive sunlight that is more direct than in the rest of the world, but most people who live in these areas have a pigmented skin that offers protection against the sun’s harmful rays. There are however congenital disorders that greatly increase an individual’s sensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) light. For people suffering from these conditions, life in the tropics can be extremely cruel. They can easily get sunburnt and are at risk of severe actinic damage and skin cancer. The prevalence of two auto-somal recessive genetic conditions, oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) and xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), might be low globally but can in some tropical countries be relatively high.[1,2]

Early sun protective interventions and treatments in photosensitive patients have a positive impact on morbidity and mortality.[1-3] It is therefore crucial that they are diagnosed with the condition and treated as soon as possible.

Sun exposure and development of skin cancer

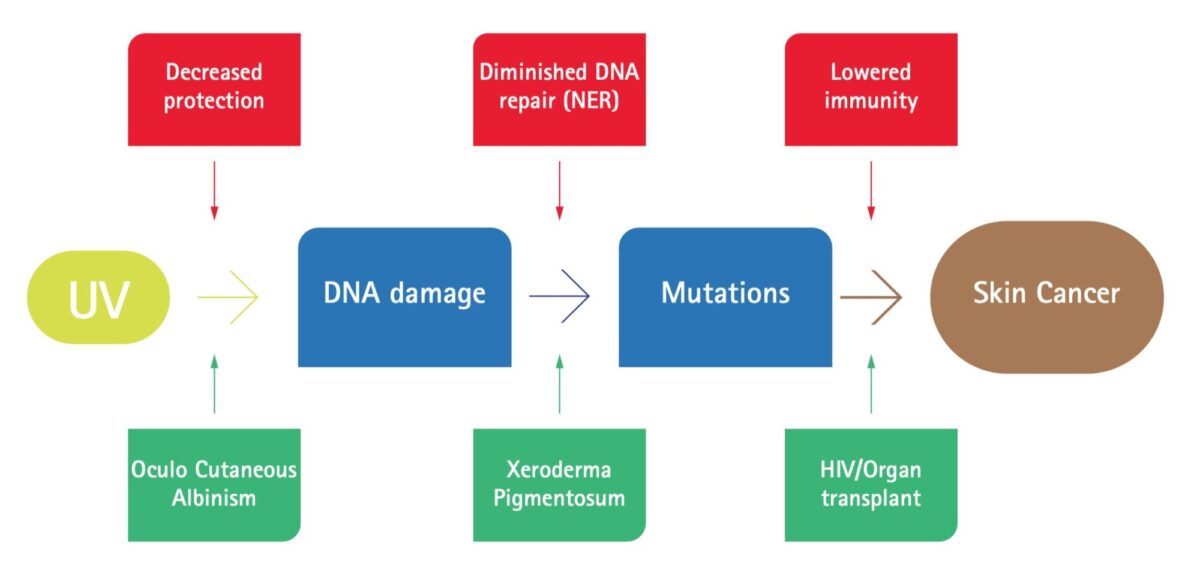

Figure 1 shows a simplified but use-ful model of photo-carcinogenesis. UV exposure causes DNA damage in the skin cell. This leads to mutations and eventually uncontrolled growth, skin cancer. There are acquired and inher-ited factors that block UV-exposure to cells. These include pigmentation, thickness of the skin and hair growth. Persons with albinism (PWA), have a complete absence or decreased biosyn-thesis of melanin and are therefore highly susceptible to DNA damage.[1,4,5]

Complicated repair pathways, especially the nucleotide excision repair (NER) mechanism, eliminates damage before it causes mutations. NER is a process in which DNA structural anomalies are recognized, removed and replaced by correct DNA. Patients with XP have a deficiency in NER and as a conse-quence develop multiple cancers, often starting from a very young age.[2,3]

Finally, mutations can be identified and attacked by a healthy immune system before they develop into skin cancers. This explains why people with an impaired immune system, such as HIV-patients or patients on immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. organ transplant recipients), have an increased risk of malignancies.

Oculocutaneous albinism

Persons with albinism have a normal amount of melanocytes in the epi-dermis but these are dysfunctional, causing total or partial absence of melanin pigment in skin, eyes and hair. This predisposes individuals to actinic damage and eventually full-blown skin cancers. These patients also frequently suffer from ocular pathology, reduced visual acuity, photophobia and refractive errors.[1,5]

The most common known types are classified as OCA types I (A and B) to 4. The global incidence of albinism is 1:20,000 individuals, but there are certain areas with much higher esti-mated rates like the indigenous Guna Yala (Panama and Colombia) 6.3:1,000 and Tanzania 1:1500. OCA-1 is most commonly found in Caucasians; OCA-2 is the prevailing subtype in Africa.[1]

Persons with albinism are not only physically disadvantaged; their distinc-tive features can also create psycho-social problems. Lack of understanding of the genetic cause of OCA generates a widespread belief in ‘magical pow-ers’, as people wonder how it is possible that two dark skinned people can be the parents of a white child. An inde-terminate number of PWAs have been persecuted and become the victims of brutal attacks and murder in the name of witchcraft, superstition and wealth. Various crimes against them have been reported such as infanticide, kidnap-ping, amputations and decapitations, committed for purposes of supply-ing highly valued body parts used for amulets. This results in PWAs living in a constant state of guilt and angst, hiding out of fear, and with restricted social integration into the society.[4,6]

Xeroderma pigmentosum

In a population where most individuals have a coloured skin, it is usually not difficult to identify a baby born with OCA, due to the clearly distinctive ‘fair’ skin. However, the situation is quite different with XP patients, who are usually born without visible abnor-malities. Their skin soon becomes dry and scaly with multiple lentigines.[2] Seven genetic subtypes of XP, so called complementation groups (XP-A through to XP-G), have been identified, based on different mutations in the NER pathway. The mutation related dysfunction can affect recognition of the DNA dam-age, the unwinding of DNA strands, or the replacement of abnormal sections by the proper nucleotides. Although these complementation groups slightly differ from each other phenotypically, with a minority of patients also suffer-ing from neurological abnormalities, extreme sun sensitivity of skin and eyes is a common feature. Depending on the amount of UV exposure, XP patients develop actinic damage with severe scarring of the skin and conjunctiva and eventually multiple cancers. They have a nearly 10,000 times higher risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer (basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas) and 2,000 times higher risk of melanomas. About 20% of XP patients develop a tumour on the tip of the tongue that can be malignant squamous cell carcinomas or benign pyogenic granulomas.[2]

Xeroderma pigmentosum in the global population is very rare; rates in Europe and the United States of America are estimated to be around 2.3 per mil-lion inhabitants. In populations where consanguinity is more common, the numbers are much higher. Northern and Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East have a much larger incidence of XP-C in particular. The most common complementation group in Japan is XP-D; prevalence there is thought to be about 1:22,000 inhabitants.[1]

Management

The relatively high number of PWAS in particular but also of XP patients in some tropical countries emphasizes the need for awareness and the availability of interventions to address the medical, psychological and social needs of such vulnerable populations.[4] Treatment therefore requires a multidisciplinary approach, including dermatologists, ophthalmologists, surgeons, patholo-gists, specialized nurses, psycholo-gists and social care health workers.[2] Management in most tropical countries would, however, unfortunately be very challenging due to financial, infrastruc-tural and sometimes socio-cultural cir-cumstances.[4] Still there are some great initiatives aimed at improving the life of these patients. A good example is the Regional Dermatology Training Centre (RDTC) in Moshi, Tanzania, which runs a thriving outreach project with a mobile skin care clinic for PWA and XP patients.[5,8] They also produce their own sunscreen (Kilimanjaro suncare®).[2]

As is evident from Figure 1, the risk of skin cancer is proportional to the accumulated amount of UV radiation absorbed by the skin cells (keratino-cytes). It is therefore of utmost impor-tance to limit sun exposure as much and as soon after birth as possible. Personal protection can be achieved by wearing a wide brimmed hat, using sunglasses, and frequently applying sun protection cream (SPF 50). An UV-blocking visor, if available, should be worn during daylight exposure, and outdoor activities are preferably performed from dusk to dawn.

A successful implementation of protective measures can only be achieved if patients and their fam-ily and community are truly aware of the benefits of these. Health educa-tion is therefore very important. The RDTC uses fellow sufferers for educa-tion and instruction, as it is thought to be more likely that the patient will accept and follow their advice.[4,7,8]

Immediate treatment of pre-malignan-cies will reduce the risk of progression into invasive carcinoma. Different modalities can be used including cryo-therapy, photodynamic therapy, and the combination of curettage and coagula-tion. The use of tumour-protective oral retinoids (acitretin and isotretinoin) has been shown to be beneficial in some cases. Of course, one should be aware of the adverse effects of these medicines in young patients, especially skeletal abnormalities and inhibition of growth due to premature epiphyseal closure. Studies have proven the use of topical ointments as a field directed therapy, including 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod. This can be particularly helpful for larger areas of dysplastic skin. Larger tumours are preferably removed by excision. A pathologist who is experienced in dermatological pathol-ogy is another requisite to examine the margins of the excised tumour for total removal. Radiation therapy seems not to be a first-line treatment and should only be reserved for inoperable tumours.[2,3]

Note by the author

Some of the photographs in this article have been previously used in other publications by the same author R.K. Horlings. These photographs have been taken by the author, courtesy of the Regional Dermatology Training Centre (RDTC) in Moshi, Tanzania.

References

- Marçon CR, Maia M. Albinism: epidemiology, genetics, cutaneous characterization, psychosocial factors. Ann Bras Dermatol. 2019 Sep-Oct;94(5):503-20. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2019.09.023

- Horlings RK, Mavura DR. Support and treatment of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) patients in Sub-Saharan Africa. Comm Dermatol J. 2017;13:1-12

- Horlings RK. Behandeling en begeleiding van patiënten met xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) in Sub-Sahara Afrika. NTVDV. 2015;25(8):404-9

- Hong ES, Zeeb H, Repacholi MH. Albinism in Africa as a public health issue. BMC Public Health. 2006 Aug 17;6:212, doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-212

- Lookingbill DP, Lookingbill GL, Leppard B. Actinic damage and skin cancer in northern Tanzania: findings in 164 patients enrolled in an outreach skin care program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Apr;32(4):653-8. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90352-6

- Cruz-Inigo AE, Ladizinski B, Sethi A. Albinism in Africa: stigma, slaughter and awareness campaigns. Dermatol Clin. 2011 Jan;29(1):79-87. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.08.015

- Horlings RK. Afrikaanse albino’s lijden onder stigma: steun van de overheid hard nodig. Medisch contact. 015 Oct 8;41

- McBride SR, Leppard BJ. Attitude and beliefs of an albino population toward sun avoidance: advice and services provided by an outreach albino clinic in Tanzania. Arch Dermatol. 2002 May;138(5):629-32. doi: 10.1001/arch/derm.138.5-629