Main content

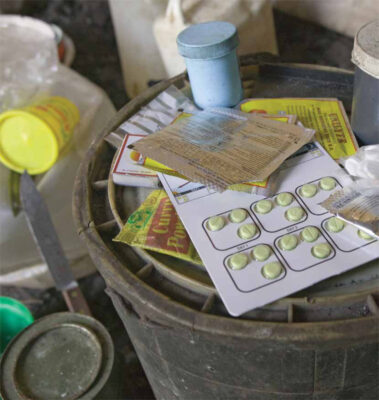

In the late nineties, the magnitude of the AIDS crisis drew attention to the fact that millions of people in the developing world did not have access to the medicines they needed to treat disease or alleviate suffering. In 2000, only one in a thousand people living with HIV in Africa had access to treatment. Highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) was available in wealthy countries and had changed AIDS from a death sentence into a manageable chronic disease. But the drugs (ARVs) were available only from originator companies, who controlled the patents. They produced small quantities carrying paralysing price tags of USD 10,000 to USD 15,000 per person per year.

The high cost of HIV medicines focused attention on the relationship between patent protection and high drug prices. (1) The difficulties developing countries experienced in paying for new essential medicines needed to treat the millions of people that were dying of AIDS raised concerns about medical patents.

It is ironic that the access to HIV medicines crisis hit just after countries had agreed to the 1994 World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which sets out global minimum standards for the protection of intellectual property (IP). The TRIPS Agreement obligated all WTO member countries to grant patents with a minimum of 20 years duration and to grant patents in all fields of technology, making it impossible to exclude medicines and food from patenting.

The global mobilization around HIV led to the introduction of a number of IP related mechanisms, some of which were contained in the 2001 WTO Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, to bring down the price of antiretroviral medicines. (2) These mechanisms include the use of flexibilities in TRIPS, the delay of medicine patent enforcement for least developed countries, the introduction of strict patentability criteria to limit the number of patents granted and to prevent ‘ever-greening’ of patents, and in 2010 the establishment of the Medicines Patent Pool, a United Nations backed initiative that negotiates patent licences to enable generic producers to make and sell affordable versions of HIV medicines. Today, first-line ARV regimens are available from generic suppliers for USD 95 to USD 158 per person per year, (3) a sharp decrease from the USD 10,000 to USD 15,000 of a decade and a half ago.

Whether these mechanisms to reduce medicine prices will also be applied to increase access to new essential medicines remains an open question. In May 2015, the World Health Organization added several important medicines, (4) including medicines for the treatment of cancer, tuberculosis and hepatitis C, to its Model List of Essential Medicines (EML). The uniqueness of these medicines – aside from their value as treatments for devastating illnesses – lies in their high price. Now that the WHO has given these medicines the status of “essential”, they must be made both available and affordable. As innovative new medicines are increasingly patented around the world and thus only available at monopoly prices that prevent widespread access, a public policy response is needed to address the intellectual property challenges associated with essential treatments. Perhaps it is time for an essential medicines patent pool to ensure that the generic production of all WHO essential medicines can take place.

High drug pricing is justified by the pharmaceutical industry as compensation for the cost of research and development (R&D) of new drugs. Without patents, they argue, pharmaceutical R&D will come to a standstill. Commercial companies will indeed not invest in the development of a new product if it cannot generate significant profits. The huge profits sustained by the patent system, however. affect priority setting in R&D by companies. Companies do not consider it profitable to invest in the development of medicines for people with limited or no purchasing power. The situation with regard to the neglected diseases crisis, first described by Médecins sans Frontières in its 2001 seminal report ‘Fatal Imbalance: The Crisis in R&D for Neglected Diseases’ (5), is still much the same today despite the globalization of stronger intellectual property protection. (6) Although there have been several new R&D initiatives launched over the past 10-15 years, progress has been incremental, for example in the field of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and based on not-for-profit initiatives.

The lack of medical innovation and the lack of access to health tools (including medicines, diagnostics, and vaccines) to address global health needs are now well-documented and widely recognized. The industry also recognizes that the current innovation system is detrimental to dealing with global health needs. For example, in response to questions about the role of the pharmaceutical industry in dealing with the Ebola outbreak in West-Africa, Andrew Hollingsworth, policy manager of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, said, ‘Unfortunately, the standard economic model for drug development, in which industry takes all of the risk in R&D and gets a return on investment from successful products, does not work for diseases that primarily impact low-income countries and developing healthcare systems.’ (7)

In 1958, the economist Fritz Machlup wrote about the patent system, ‘If we did not have a patent system, it would be irresponsible, on the basis of our present knowledge of its economic consequences, to recommend instituting one. But since we have had a patent system for a long time, it would be irresponsible, on the basis of our present knowledge, to recommend abolishing it.’ (8)

No one is suggesting the abolition of the patent system. However, based on today’s knowledge of the challenges for both access to and innovation of the current pharmaceutical development system, we urgently need to look at alternatives. We need a mechanism to bring the price of new essential medicines down so they become affordable to the people and the communities that need them. One could imagine an essential medicines patent pool to make that happen. Equally important is ensuring that research and development for new essential treatments takes place. New financing models for R&D need to provide the correct incentives for innovation while keeping drug prices low. Such models should be based on delinkage principles in which the cost of R&D is delinked from the price, in other words innovation that is no longer dependent on the ability to charge high prices. (9) At its assembly in 2016, the WHO will consider recommendations for an international medical R&D treaty made by a group of experts convened by the WHO in 2012 to better prioritise R&D projects and share the cost of such R&D. (10, 11) These international talks provide an opportunity for the medical community to step up engagement with an issue that for too long has been the exclusive domain of trade, business and IP experts and to rewrite the rules so that much needed innovations in health care can be financed and are accessible to all in need of them.

We need a mechanism to bring the price of new essential medicines down so they become affordable to the people and the communities that need them. One could imagine an essential medicines patent pool to make that happen.

Notes and references

- A patent is the right granted to an inventor by a State, or by a regional office acting for several States, which allows the inventor to exclude anyone else from commercially exploiting his invention for a limited period, generally 20 years (WIPO).

- ‘t Hoen E, Berger J, Calmy A, Moon S. Driving a decade of change: HIV/AIDS, patents and access to medicines for all. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 2011; 14(1), 15.

- Untangling the Web of antiretroviral price reductions: 17th Edition – July 2014 http://www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_UTW_17th_Edition_4_b.pdf (accessed 29 July 2015).

- http://who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/new-essential-medicines-list/en/

- Médecins Sans Frontières. Fatal imbalance: the crisis in research and development for drugs for neglected diseases. Geneva 2001. http://www.msfaccess.org/our-work/neglected-diseases/article/958 (accessed 29 July 2015).

- Pedrique B, Strub-Wourgaft N, Some C, et al. “The drug and vaccine landscape for neglected diseases (2000-11): a systematic assessment.” The lancet global health 1, no. 6 (2013): 2371-2379.

- http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/oct/05/ebola-america-range-big-pharma

- ‘t Hoen E. The global politics of pharmaceutical monopoly power: drug patents, access, innovation and the application of the WTO Doha Declaration on TRIPS and public health. AMB Publishers, 2009. http://www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_assets/Access/Docs/ACCESS_book_GlobalPolitics_tHoen_ENG_2009.pdf (accessed 29 July 2015)

- Love J. The de-linkage of R&D costs and drug prices through the Prize Fund for HIV/AIDS will cost less, expand access, accelerate and improve innovation, and replace an incentive system that is expensive, inefficient and unsustainable. 2012. Testimony before United States Senate, Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, Subcommittee on Primary Health and Agency on The High Cost of High Prices for HIV/AIDS Drugs and the Prize Fund Alternative. http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Love.pdf (accessed 29 July 2015)

- WHO Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development (CEWG): Financing and Coordination (2012) Research and development to meet health needs in developing countries: Strengthening global financing and coordination. Available: http://www.who.int/phi/CEWG_Report_5_April_2012.pdf (accessed 29 July 2015).

- Moon S, Bermudez J, ‘t Hoen, E. Innovation and access to medicines for neglected populations: could a treaty address a broken pharmaceutical R&D system? PLoS medicine, 2012; 9(5), 522.