Main content

We are increasingly familiar with the bad news about climate change, but is there a good news story on climate change and health? We asked Sir Andy Haines – keynote speaker at the 2019 NVTG symposium on Climate Emergency – to enlighten us on the options to address the current climate emergency and emerging issues in health aggravated by climate change. For more than three decades, Sir Andy Haines has been active on the interface of environmental change and public health, currently as Professor of Environmental Change and Public Health at the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (LSTMH). Before giving the floor to Prof Haines, in the first two paragraphs we briefly introduce the concept of planetary health and dimensions of how climate changes are impacting on health. [2,3,4,5,6]

The impact of global warming on health

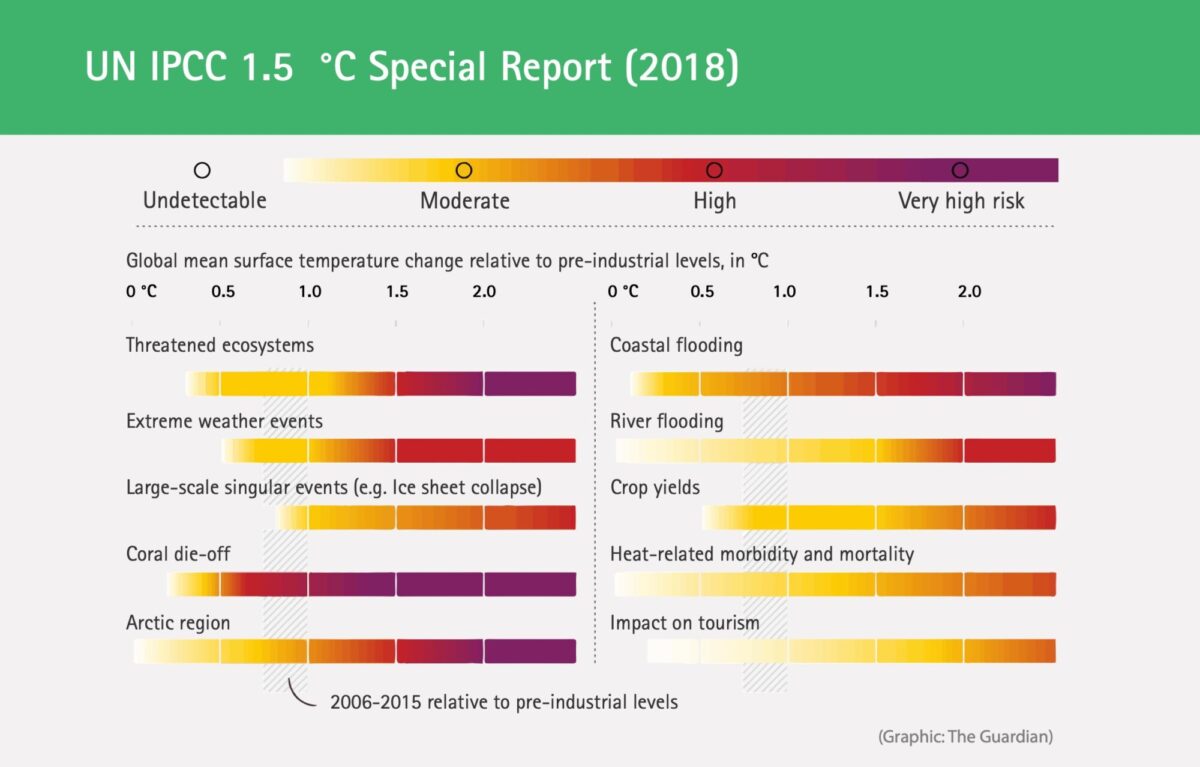

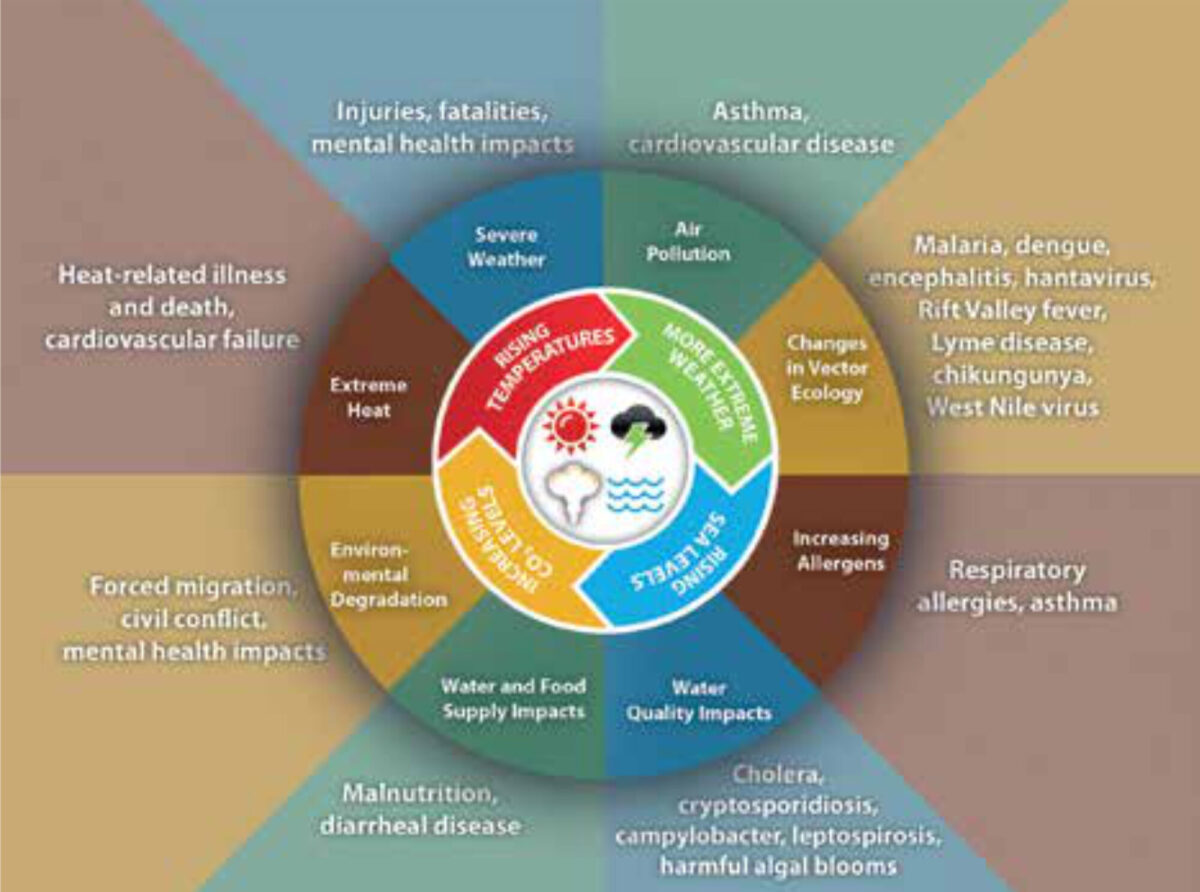

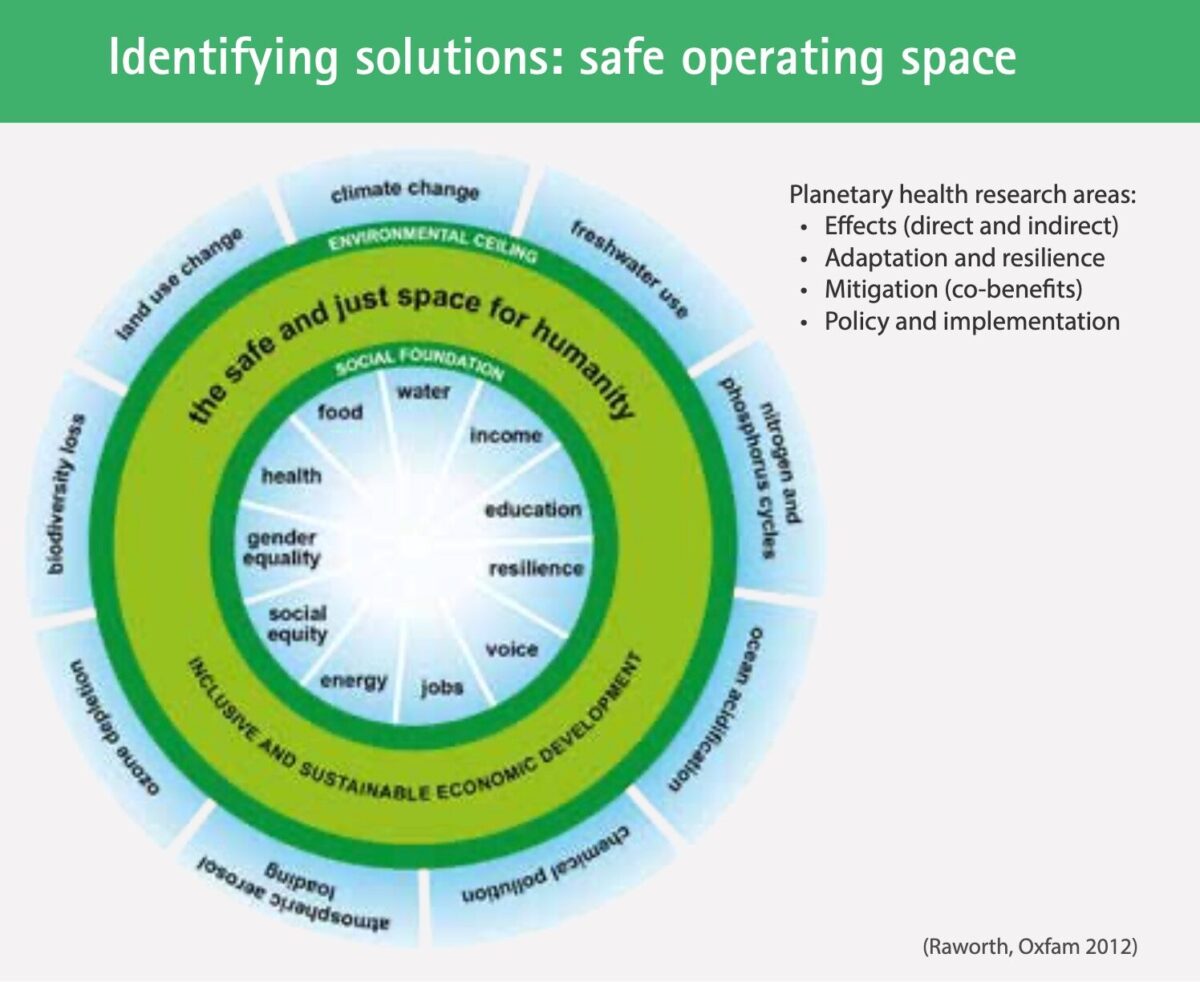

The Lancet Commission on planetary health defines planetary health as ‘the achievement of the highest attainable standard of health, wellbeing, and equity worldwide through judicious attention to human systems that shape the future of humanity and Earth’s natural systems that define the safe environmental limits within which humanity can flourish’. [7] Or, to put it more simply, ‘planetary health is the health of human civilisation and the state of the natural system on which it depends’. With these words Andy Haines introduces the concept of planetary health to an audience of scholars on the occasion of the launch of the Centre on Climate Change and Planetary Health at the LSTMH in which he talks about how we, global health professionals, have largely neglected the foundation of human health, the natural systems.[2] We have assumed that global health would continue to improve, based on the dramatic improvements in human health we have witnessed over recent decades, like increased life expectancy and major decreases in infant and maternal mortality. These are great improvements no doubt, though they may easily be reversed if we continue neglecting to address climate change challenges. Without very rapid cuts in our current greenhouse gas emissions, we are facing a 1.5 °C global temperature increase (above pre-industrial levels) over the next few decades. The warming will have dramatic consequences for human health and the livelihood of populations, as depicted in Figure 1, such as flooding, extreme weather events and threatened ecosystems with potentially dramatic direct and indirect impacts on human health (Figure 2).

Human progress at a cost

The Planetary Dashboard (Figure 3) presents a set of 24 global indicators which reflect the patterns of human activity from the start of the industrial revolution in 1750 up to 2010, as well as the changes in Earth’s systems, including greenhouse gas levels, ocean acidification, deforestation and biodiversity loss. [8]

The 12 indicators on the left depict human activity, like economic growth, population, transportation and water use, and those on the right major environmental components of the earth system, like carbon and nitrogen cycles and biodiversity. Human and earth systems trends show similar patterns with a dramatic shift starting in the 1950s, tagged as the Great Acceleration. There is strong evidence that key components of the earth system have moved beyond the natural variability exhibited in the last 11,500 years (since the beginning of the Holocene epoch, which began at the end of the last glacial period), which has led us into a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene epoch, characterised by the dominant effects of humans on the earth systems. [9]

Could you describe your personal journey into the domain of planetary health, climate change and health?

‘For many years I was a practicing clinician and academic in the field of primary care, with training in primary care and public health. In the early 1990s, I was getting more interested in the issue of climate change and its implications for human health, though it did not appear high on the agenda in those days. I was contacted by the late Prof Tony McMichael – a well-known epidemiologist who sadly died in 2014 – who shared my interest and concern. [10] We wrote technical papers on the possible impact of climate change on health, collaborated in the 1996 WHO/WMO/ UNEP report on climate change and health, and became involved in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). As I became more aware of the details of these environmental changes and of the complexity of the relationship with human health, my interest began to grow. During the ten years I was Director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (2000 – 2010), I was able to keep up some of my work – for example with a series in the Lancet in 2009 in which we looked at the health co-benefits of mitigating climate change (cutting greenhouse gas emissions), and how that would benefit human health in the near term. [11] I was particularly interested in the near-term benefits of behavioural changes – like cutting greenhouse gas emissions because it does have a direct effect on people’s daily lives and at the same time has a positive effect on the (long-term) process of climate change. After my period as Director of the LSHTM, I was asked by the editor of the Lancet to chair the Rockefeller Commission on Planetary Health, a commission that looked at the complexity of the relationship between a whole range of different global environmental changes – not just climate change – and human health. We also tried to outline potential solutions to adapt to environmental change, and particularly to reduce, or reverse where possible, these dramatic environmental changes that are occurring around the world. Briefly that is the kind of journey I travelled, keeping a focus on climate change and health, and expanding into work on sustainable cities, and on sustainable food systems which are essential to address the challenges of the Anthropocene epoch.’

In a column in BMJ and the Lancet series on Planetary health you make a plea for framing climate change as a health issue; could you explain the rationale behind this?[12]

‘I honestly feel that climate change is a major threat to human health, and by framing it as a health issue, the public, politicians and policy makers will be more likely to get interested in the theme because it directly affects them and the society they live in. After all, most of us are anthropocentric, wanting the best for our own species, our families and friends and the larger society in which we live. The implications for human health are obvious to me, and slowly we can see a recognition of its importance by the wider public, academics and policy makers. Also, increasingly we are seeing health professionals concerned about climate and other environmental changes, and funding institutions being prepared to invest money into this issue – albeit still very small amounts of money and very late. So it is happening and it has taken some time to mobilise opinion, but there is a change and we can certainly find a lot more interest amongst mainstream health professionals about what they can do in their work and also in their personal lives to address the challenges of climate change.’

People may feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the issue, which may have an effect on their willingness to act; is this something you recognise?

‘Yes, complexity turns people off, as they would want straightforward policies and to be able to see the effect more immediately. On the other hand, there are already many straightforward actions people can take, and sometimes policies are in place to encourage change, like eating more fruit and vegetables and, overall, a more sustainable diet which in many countries also requires a lower consumption of animal products, more active travel (walking and cycling) and less dependence on the private car, and moves to zero carbon renewable energy that is not powered by fossil fuels. These are fairly clear messages that are both environmentally friendly and beneficial to health.’

What are the main issues related to climate change that (global) health professionals are dealing with, and what can they do in their practice to adapt to the effects of climate change?

‘Increasingly we see studies that are attempting to quantify the effects of climate change on human health around the world, though we still have a long way to go as many of the effects are occurring at the back of many other changes. Health professionals should be aware of the effects of environmental changes on health patterns – like an increase in the risks of certain vector- or water-borne diseases. In Europe these can include the spread of Aedes Albopictus and increasing risks of Lyme disease and Vibrio infections. Secondly, health professionals – certainly the ones involved in public health – need to become involved in (national) adaptation plans in the case of extreme weather events, like early warning systems for heat waves or infectious diseases. Thirdly, professionals can also have a role in mitigation of emissions, for example by looking at the environmental impact of the health system itself and their own role in this. For example, if you are a respiratory physician, you can encourage your patients to use powdered inhalers instead of the pressured type. You can also address the environmental footprint of the hospitals, as there are often very wasteful practices inside the hospital itself, including the procurement of pharmaceuticals and equipment with high GHG footprints. We can also ensure that, in the future, new hospitals and health centres are energy efficient. So there is a lot that can be done by health professionals in their day-to-day and professional lives. See Figure 4 for some of the possible solutions.’

How can we create a ‘new narrative’ and ensure that solutions cross borders, that working in an intersectoral and transdisciplinary manner becomes the norm, instead of working in silos?

‘Great question, not easy to answer. Funding processes and policies are often very monodisciplinary. Also governments tend not to think and act in an interdisciplinary and intersectoral way. The responses we are looking for need to cut across the different sectors, because as much as we can accomplish in the health sector itself, if we really want to make a change we need to address the driving forces that are dramatically changing the environment around us. And there are a number of ways in which that can be done. At the UN level for example, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals are highly intersectoral and transdisciplinary. While SDG3 focuses particularly on the delivery of health care, others focus on topics which are central to the achievement of planetary health such as the provision of clean energy, sustainable cities and food systems. They may appear to be complex, and there is some criticism, but nevertheless, health and sustainability are very much at the centre of the SDGs, and many countries are taking them quite seriously and integrating them into their planning processes. We also see some funding organisations thinking about research in a different way, like the Welcome Trust, which is the largest funder of research on planetary health. The main challenge perhaps will be to change our own consciousness as we generally are brought up in a relatively narrow disciplinary sphere. This is a mode of thinking and working we would need to change, for example by changing our normal routine and starting to work across the boundaries of our profession. There are opportunities opening up, but it does take time. Also, we need to train a cadre of young researchers who are less rigid and more prepared to work in transdisciplinary teams. This is an important growth process for all of us.’

Could you reflect on the title of your keynote – imperatives for climate action to protect health?

‘The idea is clear. The reason we need to act is clear, considering the fact that we are heading to a 3 to 4 degrees C increase in global temperature by the end of the century, that we are losing species at probably more than a hundred-fold greater rate than pre-human times, and that many countries are depleting their fresh water reserves, to name just a few reasons. While generally human health continues to improve, environmental changes are likely to have a reverse effect on our health. This makes it imperative to act now before these changes become catastrophic, in order to reduce the potential risks we are facing. It also includes dealing with scepticism and a great level of denial which is surrounding the debate. Overall scepticism is not bad in itself, as this is fuelling scientific engagement. Denial and refusal to face facts is more dangerous and is a profound ethical challenge which we need to confront, as this is an organized process to undermine science.’ [13]

References

- The title is inspired by a keynote address delivered by Prof Andy Haines: https://www.climaterealityproject.org/video/climate-health-meeting-co-benefits-good-news-story-climate-change-and-health.

- Notes from key note speech at the launch of the Centre on Climate Change and Planetary Health at LSHTM (30 May 2019). See the link for the complete speech: https://panopto.lshtm.ac.uk/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=c48f4ef2-3fdb-47c6-8f36-aa5400a85853

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prAwHCtloYE.

- Haines A. Health co-benefits of climate action. Lancet Planetary Health 2017;1. http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanplh/PIIS2542-5196(17)30003-7.pdf;

- Haines A, Amann M, Borgford-Parnell N, et al. Short-lived climate pollutant mitigation and the sustainable development goals. Nature Climate Change 2017;7: 863-9.

- Shindell D, Borgford-Parnell N, Brauer M, et al. A climate policy pathway for near- and long-term benefits. Science 2017;356(6337):493-4.

- https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/planetary-health.

- [https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2015-01-15-new-planetary-dashboard-shows-increasing-human-impact.html.

- Idem.

- Reading tip: Antony J. Mcmichael (1993). Planetary Overload: Global Environmental Change and the Health of the Human Species. Cambridge University Press. See book review elsewhere in this edition of MTb.

- Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: household energy. Series Health and Climate Change. The Lancet 2009; 374 (9705): 1917-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61714-1.

- Andy Haines: Climate change must be reframed as a health issue. BMJ, January 2018. (ref) and, Haines A. Health co-benefits of climate action. Lancet Planetary Health 2017; 1. http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanplh/PIIS2542-5196 (17)30003-7.pdf.

- Reading tip, 2 historians presenting the case of how institutions and people are putting out false information on tobacco, asbestos, climate change: Oreskes N., Conway E.M. (2015). The merchants of doubt. How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury.