Main content

In this paper I will focus on the (financial) barriers of orthopedic surgery in Low-Income Countries. I will focus on the treatment of clubfoot, but comparable prob-lems arise for other diseases or injuries. A clubfoot is a common disorder (1:1000 births) which if left untreated will result in a child growing up with a disability that causes societal stigma, reduces mobility, and threatens their potential productivity. This loss of productivity and lifelong income is much higher than the relatively low treatment costs if the treatment starts before the walk-ing age. With a timely and correct treatment the foot will be almost normal. The Ponseti treatment provides a foot, in over 95% of the cases, which is completely functional and pain free if started before the walk-ing age. However, most of the studies with this high amount of successful treatment are from industrialized countries. [1,2,3,4] There are, however, some good publica-tions about introducing this technique and its barriers in LMICs (Low- and Middle-Income Countries) in Asia [5,6,7,8], South America [9,10,11] and Africa. [12]

Given this relatively simple and cheap treatment the question arises why the neglected clubfoot still exists.

Barriers

Barriers are known to be different between different countries, but also within countries [6,7,9]. I treat clubfoot patients in Indo-nesia both in Sumatra and Bali and especially the difference in beliefs regarding the cause of the deformity is striking. In Bali the main religion is Hindu and the cause of the clubfoot is often described as “supernatural” or “given by God” and the first treatment parents search for is the holy man, especially to prevent the next child from a disability, not necessarily for the treatment of this child. [13] These presumed misdeeds of the family together with societal stigma can cause a barrier for the caregivers to seek or continue the treatment. Other known barriers are lack of physician, education and resources, lack of physical access to health care, the family situation and the physical distance to the place of treatment. [9] It is important to realize that many factors are interrelated: patients from rural areas have to travel farther, have a lower income, don’t get any income for the days that they have to go to hospital, and in general they are more religious compared to people from urban areas. Two more important differences as compared to the (over)developed countries are the financial and social burdens for a family when their child is not able to work or to marry and start a family of its own. Especially girls with a physical handicap have difficulty in finding a partner [5] and our experi-ence in a large rehabilitation clinic showed that quite often the patients find their partner in the clinic and start a family with two physically disabled parents. In most publications footwear is hardly mentioned [5] and a person with a treated clubfoot who is able to walk on custom-made shoes in my home country might not be able to walk barefoot or with flip flops which is the custom in most of the Low-Income Countries.

Financial burden

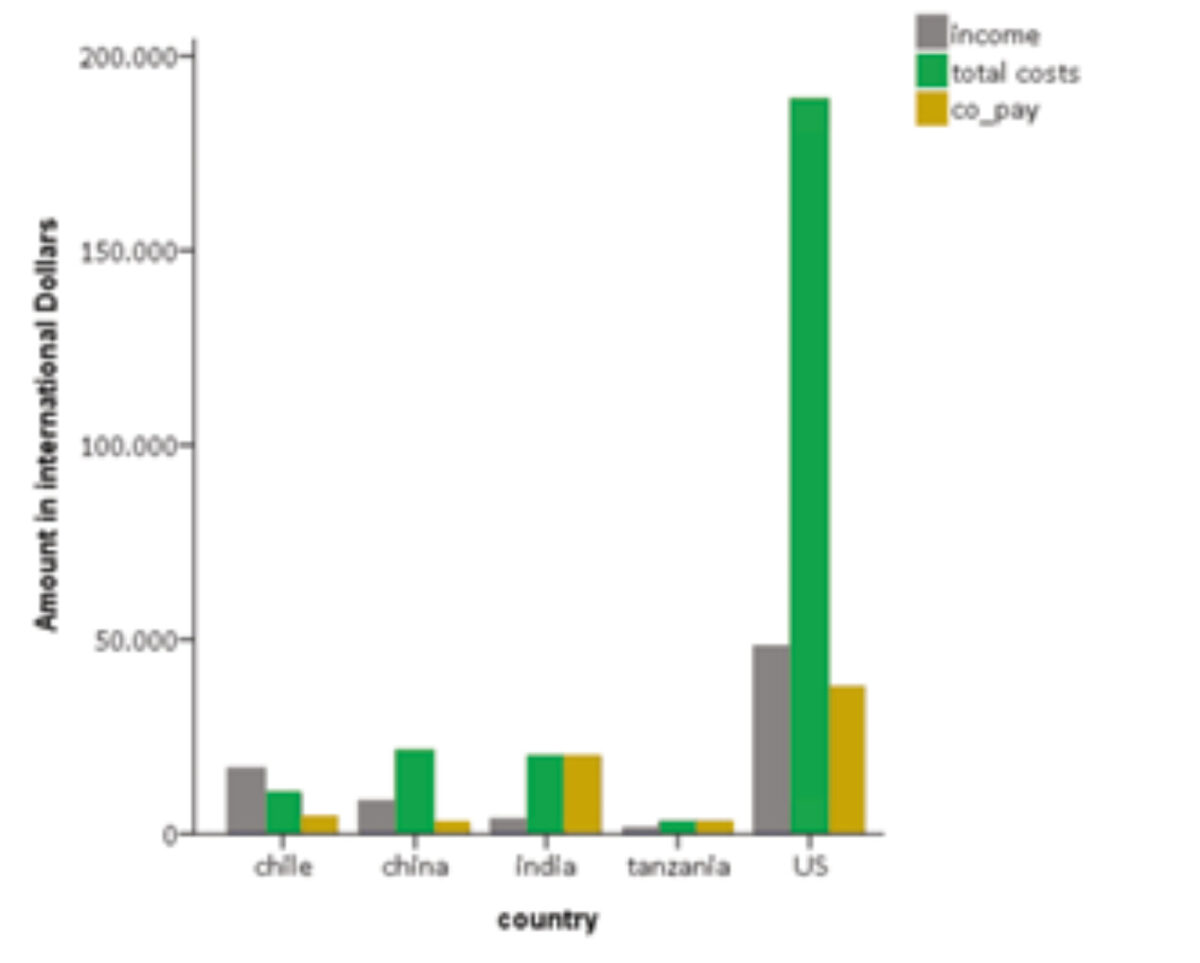

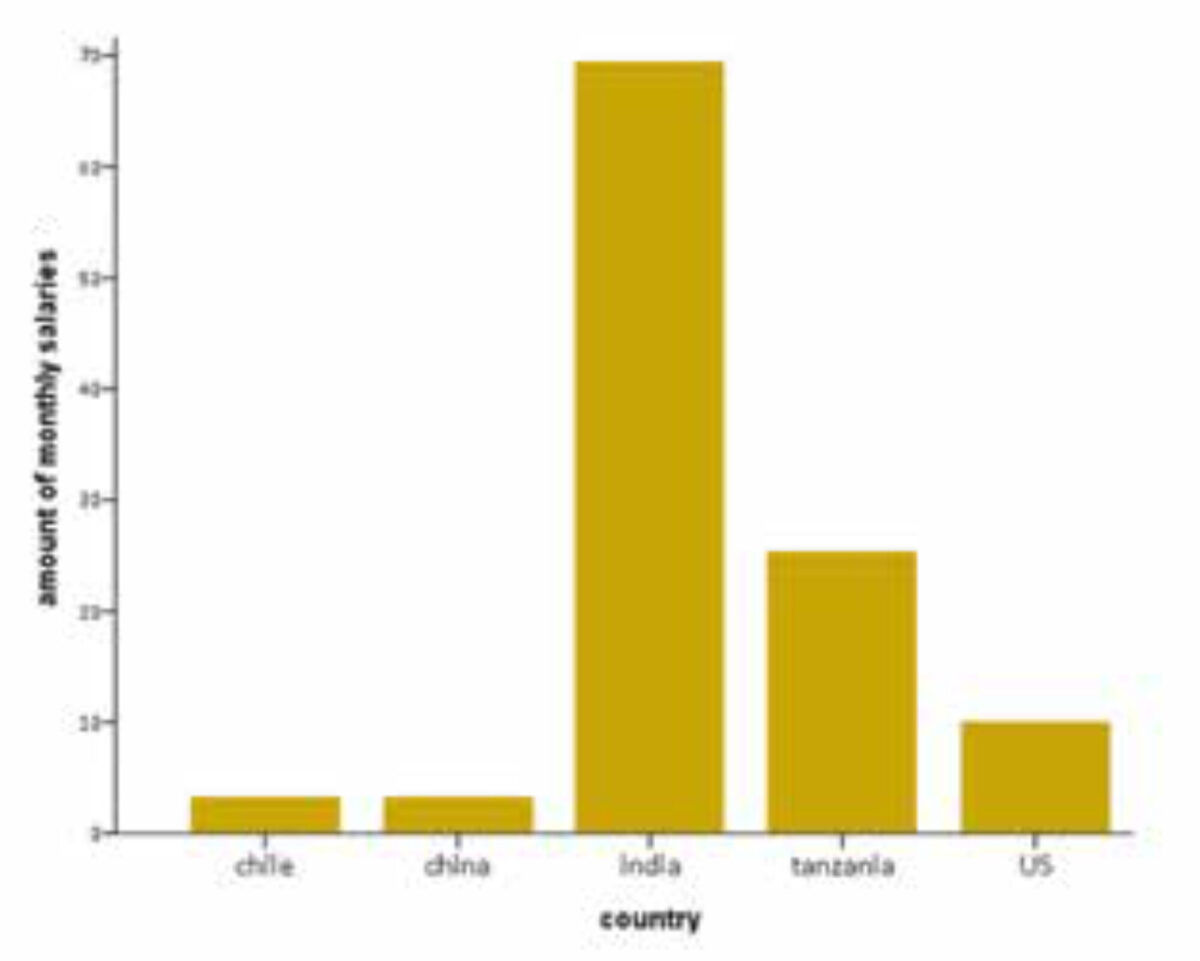

The barriers that undermine the outcomes of a Ponseti club-foot programme are primarily poverty and noncompliance with the extended post-casting brace protocol. [12] A nice comparison has been made [14] between the treatment costs of complicated diabetic foot ulcers in four countries on four continents. The treatment costs were transformed to US dollars, taking into ac-count the part of the costs which were covered by the insurance and which part the patients had to pay themselves (co-pay). When comparing the treatment costs per country, you see huge differences, but when you take into account which part of the treatment has to be paid for by the patients, the differ-ence is even larger and the graphs change a lot (Figure 1). In general, the countries with the highest treatment costs also have insurances which cover up to 100% of the treatment costs. When you take into account the amount the patients have to pay themselves the differences between the countries become much larger. In this example the average salary for that specific country has been used, but in real life the incomes are much lower for the majority of patients. Figure 2 shows the amount of monthly income the patient has to pay for his treatment. Even when the treatment is free of charge or paid for by a third party, the costs for transport and missed working days form a barrier, although there is a large difference between countries. For example in the Netherlands all treatment costs are insured and the parents only have to pay the travel costs, which is in to-tal less than 5% of their monthly income. In Indonesia parents pay up to 40% of their monthly salary only for travel costs to and from the hospital, and even though the treatment is free of charge, the parents cannot afford the travel expenses. In general the parents are “paid daily” so on the days they are in hospital there is no income for the family. This is a major rea-son for not initiating, or early withdrawal of, the treatment. [7]

The greater distance and travel time to the place of treat-ment for clubfoot, the later in life the treatment of clubfoot is started. [13] Physical accessibility of a treatment centre is also a barrier for the treatment and it also influences the adherence to the treatment which requires weekly visits in the casting phase and frequent follow-up during the bracing protocol. Non-compliance to follow-up leads to non-adherence to the bracing protocol which results in a 17-fold increased risk of relapse of the clubfoot. [10] Therefore travel distance to the place of treatment must be taken into consideration when improving clubfoot care worldwide. Specialized clubfoot clinics in rural areas were previously proposed as a solution for overcoming this barrier [9,15] and are very successful. In New Mexico, a 12.5 fold increase in recurrence was found in patients from families who had an income less than 20,000 USD a year. [15] Withdraw-al of the treatment in other settings has been reported to be between 14 and 57%. [3,11]

Supernatural beliefs and gender selection

In our own study [13] we found a 20 fold increased risk of a de-layed treatment when the parents felt the clubfoot was caused by a higher spirit or as a punishment for their own poor behaviour. Although there are almost twice as many boys than girls with clubfoot, about 80% of the patients we treat in Indonesia are boys, which raised the suspicion about gender selection, a phenomenon which is known from India, where girls are treated much later in life than boys[7]. Another astonishing phe-nomenon is the fact that some parents don’t want their child to be treated because they can get more money as a beggar with a handicapped child. [7]

Association or cause?

We looked at the age at the start of the treatment in 4 countries and found some associations. [13] We found a strong association between the age and the distance to the hospital, but also an as-sociation between distance and income. This can be explained by some general observations. On average the people in rural areas are lower educated and especially have lower health lit-eracy. They also have a lower income and need more time (and money) to travel to the hospital. All the factors are interrelated and it is impossible to determine the most important factor.

Avilucea [15] found almost the same phenomena: of eighteen in-fants from a rural area who had early recurrence, fourteen were Native American. The families of these children, like those of all of the children with early recurrence, discontinued orthotic use earlier than was recommended by the physician. Discontin-uation of orthotic use was related to recurrence, with an odds ratio of 120 in patients living in a rural area. Native American ethnicity, unmarried parents, public or no insurance, parental education at high-school level or less, and a family income of less than $20,000 were also significant risk factors for recur-rence in patients living in a rural area and are all interrelated.

Lack of information

The lack of information and skill of the doctor is another bar-rier[10] and the public opinion about clubfoot also influences the parents in seeking treatment for their children. [8,11] Several studies found a difference between the awareness of treatment possibilities in different countries and especially the difference between urban and rural areas where health literacy is, on aver-age, lower in rural areas. [7] We also experienced that the local community was not aware of treatment possibilities for club-foot and a lot of patients are referred by priests or local NGOs, often from abroad. Maybe in the future this information could be provided by digital means. Clinicians with the appropriate skills and training are an important resource in delivery of an intervention, and a number of authors studying both surgical and Ponseti techniques reported that practitio-ners’ lack of skill impacted negatively on the outcomes of treat-ment. [9,11] In some countries there is no integrated treatment protocol for clubfoot in the health care system nor the medical education. Furthermore it is not integrated in the education of obstetricians and midwives, the key health care providers for early recognition and referral. [8] Lu et al. [6] found that more than half of the treating physicians pointed at a lack of aware-ness of early recognition.

Surgical correction of a clubfoot is provided by an orthopedic surgeon; the Ponseti and some conservative techniques could be provided by clinicians with a lower level of qualification, such as physiotherapists and clinical officers. [3] In many set-tings, non-physician practitioners are primarily responsible for the casting phase of treatment, particularly in areas with a shortage of physicians. [12]

There are some nice examples of introduction of the technique through non-physician health care workers in Malawi [16] and Uganda. [12] Combined teams with both orthopedic surgeons and non-physicians are used in India, Nepal and Vietnam. [8,17]

Given that contextual factors play an important role in deter-mining the outcomes of treatment, these too must be ad-dressed in future studies to find ways of overcoming barriers posed by the context in which the intervention is provided. [3]

The future can be bright

Every year about 150,000 children are born with a clubfoot worldwide, about 80% of whom in Low- or Middle-Income Countries. The majority of these feet are not treated leaving the child disabled for the rest of its life. We as a community should try to find and overcome the barriers to treat these patients, because we have a relatively easy, cheap and highly cost-effective treatment option which can be given by trained non-physicians supervised by an interested medical doctor who is able to perform a percutaneous tenotomy. With a relatively simple treatment we can change the prognosis from a serious disability for life to an almost normal foot. Given that poverty and beliefs of supernatural causes for the clubfoot are impor-tant reasons for delay in the start of treatment, these factors should be addressed for the local situation when introducing the Ponseti technique.

The concept of small treatment centres in rural areas has been proven to be highly effective in several countries and should be the mainstay for early recognition, treatment and especially education and adherence to the treatment [5,15] as noncompliance and distance to the treatment centre [7] are the most important reason for failure. A good example of a national programme supported by orthopedic surgeons and physiotherapists from abroad is “walk for life” in Bangladesh which started in 2009 and has treated over 18,000 clubfoot patients nationwide so far and a similar project has just started in Myanmar. [5]

References

- Jowett CR, Morcuende JA, Ramachandran M. Management of congenital talipes equinovarus using the Ponseti method: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Sep;93(9):1160-4.

- Morcuende JA, Dolan LA, Dietz FR et al. Radical reduction in the rate of extensive correc-tive surgery for clubfoot using the Ponseti method. Pediatrics. 2004 Feb;113(2):376-80.

- Owen RM, Kembhavi G. A critical review of interventions for clubfoot in low- and middle-income countries: effectiveness and contextual influences. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012 Jan:21(1):59-67.

- Dereymaeker G, Witbreuk M. Treatment of the clubfoot in low- and middle-income coun-tries. MT, Bulletin of the Netherlands Society for Tropical Medicine and International Health 2014; 52, no. 4, Dec. (this issue).

- Ford-Powell VA, Barker S, Khan MS et al. The Bangladesh clubfoot project: the first 5000 feet. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013 Jun;33(4):e40-4.

- Lu N, Zhao L, Du Q et al. From cutting to casting: impact and initial barriers to the Pon-seti method of clubfoot treatment in China. Iowa Orthop J 2010;30:1-6.

- Gadhok K, Belthur MV, Aroojis AJ et al. Qualitative assessment of the challenges to the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot by the Ponseti method in urban India. Iowa Orthop J. 2012;32:135-40.

- Wu V, Nguyen M, Nhi HM et al. Evaluation of the progress and challenges facing the Ponseti method program in Vietnam. Iowa Orthop J. 2012;32:125-34.

- Boardman A, Jayawardena A, Oprescu F et al. The Ponseti method in Latin America: ini-tial impact and barriers to its diffusion and implementation. Iowa Orthop J. 2011;31:30-5.

- Nogueira MP, Fox M, Miller K et al. The Ponseti method of treatment for clubfoot in Brazil: barriers to bracing compliance. Iowa Orthop J. 2013;33:161-6.

- Palma M, Cook T, Segura J et al. Barriers to the Ponseti method in Peru: a two-year follow-up. Iowa Orthop J. 2013;33:172-7.

- Van Bosse HJ. Ponseti treatment for clubfeet: an international perspective. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011 Feb;23(1):41-5.

- Van Wijck S, Oomen M, van der Heide HJ. Unpublished data, manuscript in preparation 2014.

- Cavanagh P, Attinger C, Abbas Z et al. Cost of treating diabetic foot ulcers in five different countries. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012 Feb;28 Suppl 1:107-11.

- Avilucea FR, Szalay EA, Bosch PP et al. Effect of cultural factors on outcome of Ponseti treatment of clubfeet in rural America. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Mar 1;91(3):530-40.

- Tindall AJ, Steinlechner CW, Lavy CB et al. Results of manipulation of idiopathic clubfoot deformity in Malawi by orthopaedic clinical officers using the Ponseti method: a realistic alternative for the developing world? J Pediatr Orthop. 2005 Sep-Oct;25(5):627-9.

- Nguyen MC, Nhi HM, Nam VQ, Thanh do V, Romitti P, Morcuende JA. Descriptive epide-miology of clubfoot in Vietnam: a clinic-based study. Iowa Orthop J. 2012;32:120-4.