Main content

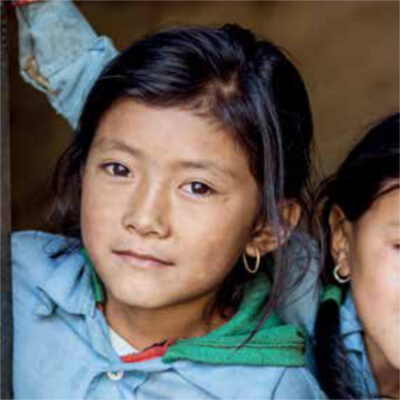

Imagine a 13-year-old girl with vaginal discharge in the rural Himalayas, Nairobi, Melbourne, or the Himba tribe region in Northern Namibia… What attention would she get, who would look after her, who would she tell, who would recognise it without her complaining, what would be the range of aetiologies, what level of care would she receive and when? Her care seeking behaviour will depend on her upbringing, her trust in her environment, the availability of services, and the sensibility of caregivers regarding the needs of the young girl.

Causes of vaginal discharge can include an acute infection or injury, congenital urogenital malformation, or female genital mutilation (FGM), depending on the context the girl is living in or has lived in.

Paediatric and adolescent gynaecology (PAD) services need more overall attention, since the subject is not an integrated part of general paediatric services at the health centre level, in Under 5 clinics , or school health programmes. Also, this sub-speciality within paediatrics is not represented in medical curricula of doctors and health workers in a structured way. Such services should be integrated into existing health care structures at all levels.[1]

The girl from our example might be left waiting to see how her condition develops, or maybe she will consult a general clinic, with inappropriate surroundings, under time pressure and an examination with insufficient tools by non-specialist staff. The handling she experiences can influence her perception of her integrity and her self-esteem. Utilisation of appropriate language, sensitive interaction, and an explanation of the steps of the examination should be integral parts of a paediatric gynaecological consultation and physical examination. Giving her the chance to follow the process, with the option of using a mirror for example, will teach her about her own anatomy in a professional way. This approach ensures that her self-determination is respected.

A study showed that, in Europe and other high-income countries such as Canada, general guidelines and best clinical practice are limited.[2, 3] There is a strong need for defining the quality of training and standard of care. It is necessary to include this subject in the curricula of undergraduates and health related professional positions.

The first contact with gynaecological services tends to happen when pregnancy occurs. Professional sexual education, including continuous guidance on contraception and protection against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), is not readily available to children and adolescents before their first sexual encounter. This is an international phenomenon despite excellent teaching and advocacy materials having been published via the WHO for many years now.[4] Paediatric and adolescent gynaecology are strongly interlinked with child protection and individual rights, but these are not respected when it comes to FGM and reproductive health issues.

Let’s also consider the situation of a young girl who is having her first sexual experience. How is she educated, where and from whom does she get support regarding the use of contraceptives, who can she address with upcoming physical discomfort and psychological problems, how can she resist cultural restrictions or contrary demands, and how can she find understanding? Acceptance in the community, access to advice, counselling opportunities, and appropriate and safe abortion facilities vary greatly internationally.[5] Integration in existing health structures should support the standard of care.[1]. A close interdisciplinary network is further needed to meet the professional demands of this discipline. Dermatology, endocrinology, surgery, infectious diseases and psychology are the disciplines that underly paediatric gynaecology.

There are many initiatives by civil societies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) underway, together with well-defined guidelines from World Health Organization (WHO) programmes. However, coverage depends on the awareness and willingness of political leaders to facilitate implementation through staff training and supervising the integration of PAD services in a child-friendly and adolescent-appropriate environment. In reality, the structured access to Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccination is an example of how fragmented scientific knowledge and programmes are translated into practice in respective contexts. Even though the vaccine has been available in high-income countries for over 15 years, implementation strategies to boost coverage in low-income countries with the highest disease burden were introduced with a delay of over 10 years. Similarly, approved methods of contraception are available to only a minority of adolescents.[5]

It is high time that professional organisations like the European Organisation for Child and Adolescent Gynaecology and the World Society of PAD adopt a proactive approach towards pushing governments to implement good clinical care for the young female generation and to educate the target group and social environment alike. Advocacy channels via WHO should support the implementation of interdisciplinary training programmes in paediatric and adolescent gynaecology.

PAD and reproductive health deal with a sensitive personal issue during a vulnerable lifetime period. Girls of all ages have the right to be cared for in an appropriate professional context over the course of their life, as a precondition for living life as they choose and realizing their potential to the full.

References

- Kangaude GD, Macleod C, Coast E, Fetters T. Integrating child rights standards in contraceptive and abortion care for minors in Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2022.159.998.1004 doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14502

- Roos E, Vatopoulous A. Health care service in paediatric and adolescent gynaecology throughout Europe: A review of the literature. Review Article| Volume 235, P110-115, April 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.08.022

- Dumont T. The current state of pediatric and adolescent gynecology residency training in Canada: a needs assessment from program directors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021; 34: 787-792.e1

- 2018 WHO recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514606

- Huneeus A, Obach A. The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module. Volume 2, Adolescent gynecology. Chapter: Social Determinants of Health in Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418153