Main content

This summary was compiled after a discussion between Mulinda Nyirenda, expert in the subject, and Ed Zijlstra on behalf of the Editorial Board of MT.

| Brief CV Mulinda Nyirenda completed her medical education at the College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi and graduated in 2001 (MBBS). She then trained in Internal Medicine in Malawi (University of Malawi, MMed, 2010) and South Africa (Witwatersrand, 2012, MMed; FCP (SA) in 2010). She is now finalising a Masters of Philosophy in Emergency Medicine at University of Cape Town. In 2010 she joined the OPD/Emergency/casualty section that later became the AETC at QECH. She is a section editor of the African Federation of Emergency Medicine (AFEM) handbook. |

Introduction

Before 2011, it was not uncommon to find a patient in the adult medical wards of Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) during the daily morning ward round who was admitted during the night because of headache and fever. Quick assessment would show that the patient was probably suffering from acute bacterial meningitis, a medical emergency condition. However, no adequate clinical assessment, including diagnostic procedures such as lumbar puncture, had been done, and appropriate (or empirical) treatment with antibiotics and IV fluids had not been started. Precious time was therefore lost which often contributed to a poor outcome in this serious disease. This was not a standalone example, but a common occurrence that painfully showed the lack of a well-functioning emergency department with a 24-hour service and skilled staff.

Infrastructure and staff

The Adult Emergency and Trauma Centre (AETC) at QECH began its operations in October 2011 with support of the Wellcome Trust, the Anadkat Family and other private donors. QECH is a tertiary referral hospital and serves the adult population of Blantyre district with a catchment area of 1.2 million people. The AETC provides emergency care for adult patients with medical, surgical, trauma or obstetric/ gynaecological conditions; a paediatric Emergency Department had existed at QECH from 2001.

The staff consists of generally trained medical and nursing staff supported by ancillary staff. The medical team is composed of clinical officers, medical interns and medical officers. All require in-house training in emergency and trauma care skills at the beginning of their rotation. There are three senior consultants who are all specialized in Emergence Medicine and offer oversight and expertise. Nurses are trained in triage and basic life support skills and basic trauma care skills that allow them to initiate life-saving emergency care and treatment as patient awaits clinical evaluation.

The departments of Internal Medicine, Surgery and Obstetrics/Gynaecology each have interns and registrars responsible for medical, surgical and gynaecological admissions and for offering consultation for other specialties.

Organization of patient care

The AETC operates on four pillars: 1. proper initial assessment using a triage system to reduce delays for patients who need treatment urgently; 2. early clinical assessment and treatment, with proper consultation and evaluation of treatment response; 3. availability of senior consultants (medical expertise) to provide early diagnosis recognition and implementation of appropriate care packages for patients; and 4. early diagnostic pathways leading to initiation of treatment before admission to the wards and reducing unnecessary hospital admissions and follow-up visits for patients.

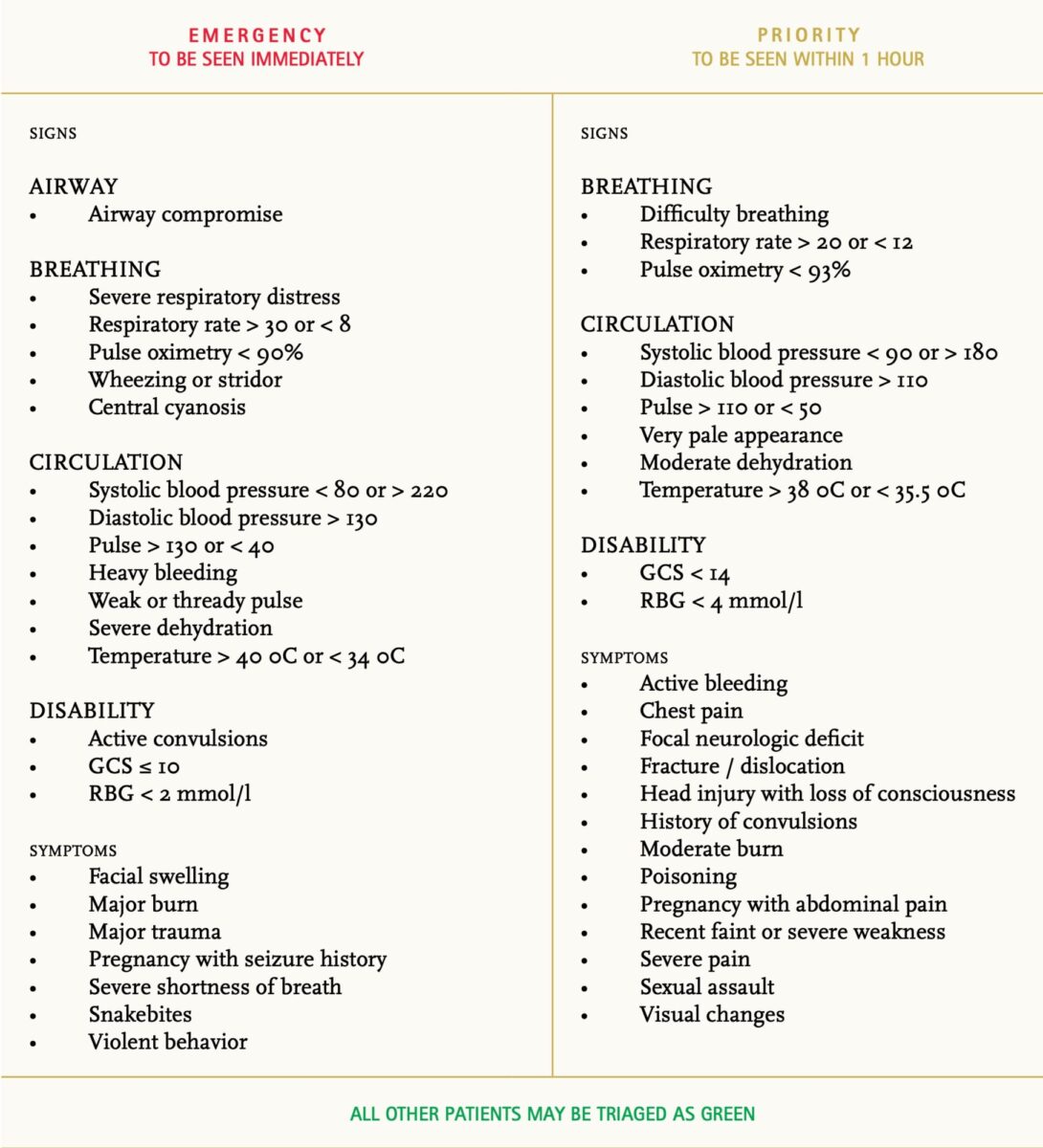

The triage system was developed locally from the South African Triage System, the Manchester Triage system, and the World Health Organisation (WHO) QUICK check tools. [1,2,3] Its implementation was guided by the local experience of the WHO paediatric Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) implementation, which has been adopted by health workers in Malawi. [4] The triage parameters include a presenting complaint and core vital signs (respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, pulse rate, blood pressure, Glasgow Coma scale (GCS) and temperature). It is a three-tiered continuous triage system coded with traffic light signs: red (emergency) indicating ‘to be seen immediately‘, yellow (urgent/priority) ‘to be seen within I hour‘ and green (queue) ‘to be seen within 4 hours of arrival‘. (Figure 1)

Senior medical expertise has improved resuscitation care for the unstable patient resulting in prompt recognition of respiratory and circulatory failure, shock, and altered mental state presentation that require stabilization. Airway management, oxygen supplementation, circulatory support and relevant intensive care monitoring are initiated and provided in the 4-bed designated resuscitation room. Patients from this area are often admitted later to the high dependency and intensive care units of the hospital.

The short-stay ward reduces unnecessary hospital admissions for patients who present for example with asthma exacerbations, non-severe malaria with gastrointestinal disturbances, gastroenteritis requiring IV rehydration as well as patients requiring observation after minor surgical procedures in the emergency department.

Outreach

In addition to care at QECH and in collaboration with the district health officer (DHO), the AETC reaches out to the health centres (HC) in Blantyre district by helping to strengthen the care given at HCs and by designing access pathways and identifying nearest gateway clinics. The Family Medicine speciality has also taken on the role of improving delivery of care in Blantyre District Health Centres. Supervision by specialists and the DHO have been strengthened. Overtime and decentralisation of care, particularly of chronic conditions, have also helped in improving primary care packages offered at health centres.

Achievements and challenges

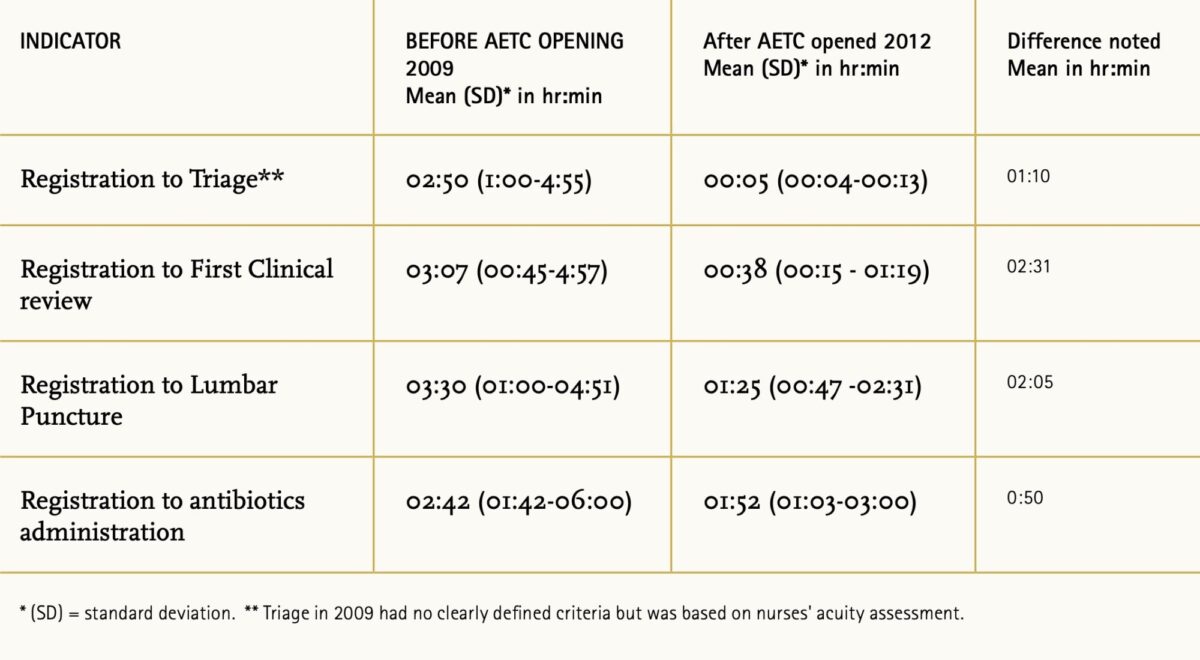

The impact of transforming the adult patient care pathway is illustrated using the acute care pathways indicators in providing care for the acute meningitis patient displayed in Table 1.

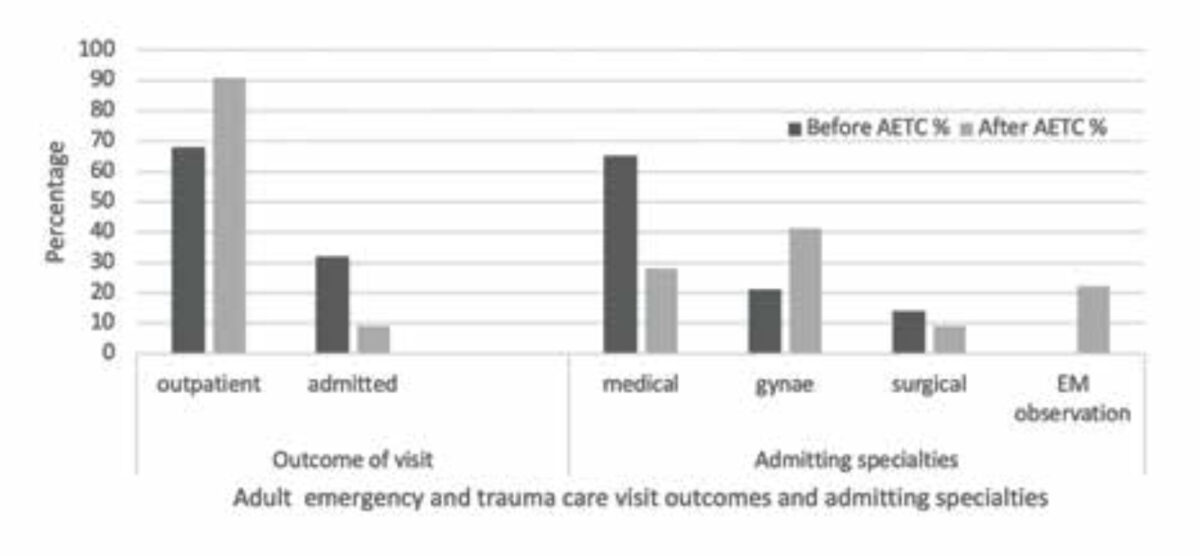

The admission rate of the adult patients decreased from 32% to 9% of all acute presentations in the hospital (Figure 2). A shift in the pattern of admitted patient load was observed; for example, there was a significant reduction in the number of patients admitted to internal medicine wards from 68% to 28%, whereas 21% of adult admissions were diverted to the emergency medicine short stay ward for observation and stabilisation. The outreach activities in Blantyre District that aimed at primary care strengthening yielded a reduction of 19% in visits to the adult emergency and trauma center between 2011 (n= 596,536) and 2012 (n = 482,571), reducing overcrowding and optimizing the care for critically ill patients. Critical care in various specialties has improved with the establishment of the AETC, resulting in better selection of patients admitted to high dependency units. The 4-bed intensive care unit of the hospital has also diversified its patient profile, which especially benefits non-surgical patients.

The AETC is an educational hub and a unique model of adult acute/ emergency care in Malawi. Medical and nursing students in undergraduate and postgraduate programs are exposed to the AETC as part of their curriculum. Since November 2017, medical interns have been doing a formal rotation in emergency medicine which is unique in the country.

Current challenges include high turnover rates in staff that affect standards of care. Overcrowding in the AETC occurs due to delays in processing of medical and surgical admissions. In addition, the AETC is still utilized for primary care and follow-up outpatient care. Limited funding from the Ministry of Health with minimal external partnerships compromises the emergency care package at various levels.

Conclusion

The AETC has transformed medical care in Blantyre district and in QECH, both conceptually and practically, in terms of understanding the concept as well as the delivery of emergency care. This has also resulted in the restructuring of primary health care in the district leading to improved care at the health centre level.

References

- https://emssa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/SATS-Manual-A5-LR-spreads.pdf

- Mackway-Jones K, Marsden J, Windle, J. Emergency Triage: Manchester Triage Group, 3rd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. 2014.

- World Health Organization (WHO) quick check and emergency treat-ments for adolescents and adults. Available from: https://www.who.int/influenza/patient_care/clinical/IMAI_Wall_chart.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization – emergency triage assessment and treatment (ETAT) course. Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241546875/en/