Main content

There is an increasing global burden of surgical disease. Despite this, many Low- and Middle-Income Countries lack surgical capacity and therefore the world’s poorest population barely has access to safe surgical care. As a consequence, the number of prevent-able deaths and disabilities is increas-ing to unacceptable levels.

In recent years, basic surgical care is slowly receiving more attention from the global health community. New evidence has propelled the recognition of surgical care into a crucial component of primary health care. This has led to a growing number of inter-national organizations, such as the WHO, to start to address the need of global access to surgical care. How-ever, there is still a long way to go for raising awareness and promoting possible interventions.

In this essay we aim to illustrate the worldwide pub-lic division in access to surgical care. We also present evidence that demonstrates surgery should be seen as a critical component of global public health. In addition, we give examples of current efforts made by interna-tional organizations to improve access to surgical care. Our purpose is to show that there are interesting op-portunities for the Dutch government and doctors to get involved in current international developments regard-ing surgical care.

* years of healthy life lost = disability adjusted life year = DALY

The public division in access to surgical care

Diseases treatable by surgery form a significant burden of disease worldwide. Injuries, complications of childbirth or cancer are responsible for 11% of the global burden of disease. [1] Pre-term birth complications form the eighth leading cause for the global burden of disease, and road traffic accidents are the tenth leading cause. For example, pre-term birth complica-tions accounted for 76,982 million years of healthy life lost* in 2010. In comparison, HIV/AIDS caused 81,547 million years of healthy life lost. [2]

Despite surgical diseases causing a significant burden of disease, there is a public division in access to safe surgical care. The poorest 2 billion people in the world receive only 3.5% of the surgical procedures undertaken worldwide, whereas the richer parts of the world receive 96.5% of all procedures. [3] Other studies show that 56 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are in need of surgical care, but do not have timely ac-cess. [4][5] This lack of access leads to a high amount of untreated diseases. A report of the United Nations Population Division estimated that 289,000 women died during childbirth in 2013. [6] It is acknowledged that this is partly attributable to the absence of timely surgical care. [7] A WHO report showed that 90% of deaths caused by injuries occur in Lower-Income Countries. [8] On top of deaths attributable to the unavailabil-ity of surgical care, there are many people living with chronic disability due to their illness. For the latter group, their living conditions could improve significantly if they had access to surgical care. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study the disability caused by neoplasm increased by 27.3% over the past two decades, whereas the disability caused by road traffic accidents increased by 33.2%. [2]

Surgery gaining recognition as global health intervention

Although surgical illnesses cause a significant burden of disease, surgical care has not been a priority of global health efforts. Currently there are no major funding programmes that invest in surgical care. This contrasts with the combat against infectious diseases, which received most of the world’s atten-tion. Nowadays there are numerous successful (funding) pro-grammes for controlling infectious diseases. For example, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria invested $3,900 million in public health interventions in 2013, the Netherlands being one of the top 10 donor countries.

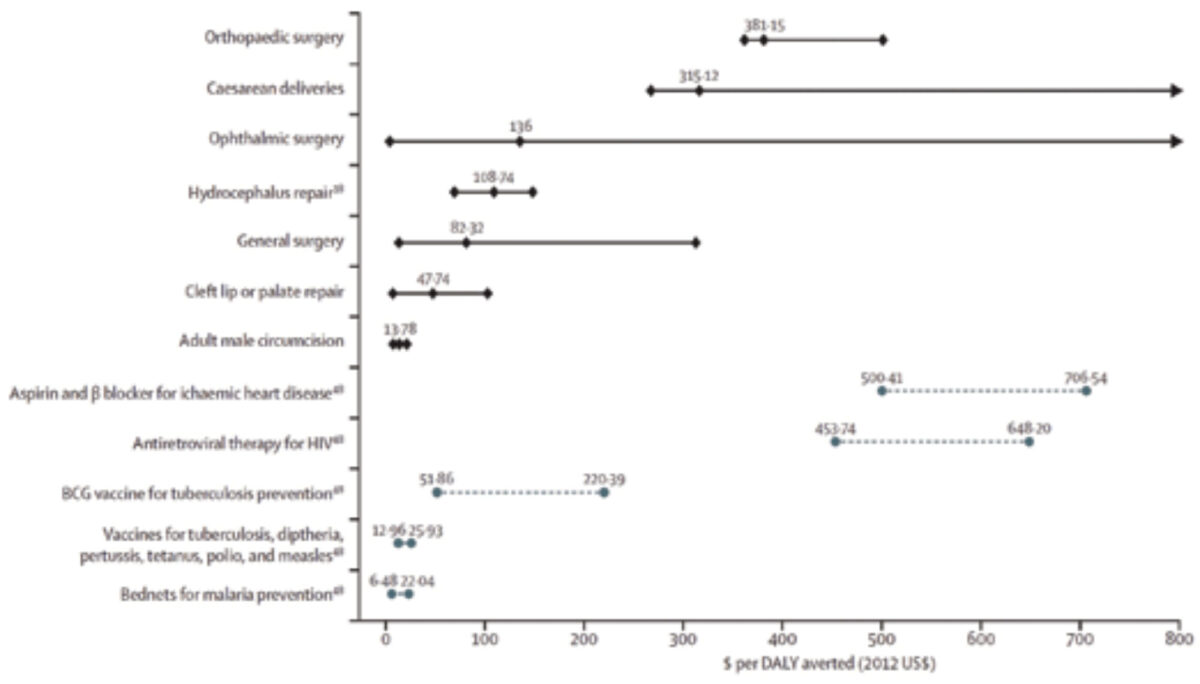

Only recently surgery has gained attention from the global health community. New research evidence has spurred the recognition of surgery as a possible global health interven-tion. Researchers have conducted several cost-effectiveness analyses and findings refute arguments that surgery would be too expensive. [9,10] To illustrate, the systematic review of Chao, Sharma, Mandigo et al. showed the cost-effectiveness of several basic surgical interventions. These interventions ranged from male circumcision to caesarean deliveries, and costs were plot-ted out for every year of healthy life won. (Figure 1) Compared to conventional global health interventions, such as HIV medi-cal treatment, these findings show that most procedures are at least equally or even more cost effective. [9]

In addition, efforts to build up surgical services can improve other parts of health care systems too. Developing surgical services will contribute to additional training of personnel, building health care facilities, establishing referral or drug delivery systems. Even though such investments will impede cost-effectiveness in the short term, they are essen-tial parts of developing health care systems in general. This is commonly referred to as diagonal development, whereas build-ing up one part of the system (vertical inputs) increases the access of the health system in general (the horizontal output). It evolves to diagonal strategies over time. [9]

To improve quality and availability of basic surgical interven-tions the focus is not exclusively on surgeons. Training of clinical officers and midwives can help to improve scalability of surgical programmes. There are several programmes that show that trained midwives can conduct surgical interventions with good outcomes. [11] They require less time to be trained and help to reduce costs.

Opportunities to engage in current developments

The arguments mentioned above have mobilized international organizations into action. An important effort emerged in 2004 when the WHO launched the Emergency and Essential Surgical Project (EESC). It aims to address the lack of surgical capacity in Lower-Income Countries. [12] The programme has made important steps forward; however, it has yet to be ad-opted by many national health policies. [13] Recently the ‘Lancet Commission on Global Surgery’ was established. Its purpose is to embed basic surgical care in the global health agenda. [14] Additionally, there is a group of several influential surgeons and academics that form the ‘International Collabora-tion for Essential Surgery’. They recently launched the 15×15 campaign in order to pronounce 2015 as the international year of surgery. They propose that 15 essential surgical conditions should be ac-cessible worldwide by the year 2030. [15]

We believe that these developments provide interesting opportunities for Dutch doctors and policymakers to play an important role in improving access to global surgical care. For example, there are Dutch doctors with experience in providing surgical care in low resource settings. These ‘Doctors in International Health and Tropical Medicine’ followed a training programme that consists of two years of training in basic surgical interventions, integrated with four months of education in tropical diseases and international health at the Royal Tropical Institute. [16,17] The training programme provides young doctors with skills to work in the field of global health. They can help to improve access to surgical care by directly providing surgical care. After having gained more experience, these doctors can contribute to knowledge translation. For example, they are capable of train-ing local personnel and building up infrastructure, thereby contributing to longer-term solutions. Finally, their knowledge and experience can be used to advise health authorities on future global health initiatives.

Today, there are many Dutch programmes and individual doctors contributing to make surgical care accessible in low resource settings. Examples of such initiatives are the ‘Werk-groep Orthopedie Overzee’, ‘Partnership for Safe Motherhood’, ‘Stichting Interplast Holland’ and the ‘Netherlands Society for International Surgery’. These programmes help to improve access in areas where there is a shortage of skilled surgeons, thereby contributing to the reduction of preventable mortality and disability. However, the cohesion and collaboration between these initiatives still have room for improvement. For example, there is currently no collaborative strategy among the aforementioned Dutch organizations. Likewise, there are no joint lobbying efforts to create awareness among Dutch doctors and policymakers.

In November 2014, the Netherlands Society for In-ternational Surgery organized a symposium ‘Surgery in Low Resource Settings’. It sought to strengthen surgical availability and skills in low resource set-tings. The event investigated the role of doctors to contribute to possible interventions. Many major Dutch and International organizations committed to surgery were present. Thereby the symposium raised the opportunity to improve mutual efforts and create stronger links between Dutch actors and international organizations, such as the WHO.

Conclusion

Surgical conditions form a major burden of disease worldwide. Yet the poorest two billion people have limited access to safe surgical care, leading to a high amount of untreated disease. Today, new evidence from research spurs the recognition of surgery as a crucial component of Global Health and develop-ment. Organizations are increasingly creating awareness of the problem and seek possible interventions. This momentum creates an opportunity for Dutch policymakers, organiza-tions and doctors to collaborate towards providing access to surgical care. The training programme of ‘Doctors in International Health and Tropical Medicine’ provides a pool of skilled doctors that can play a key role in working towards this goal. In addition, the Symposium ‘Surgery in Low Resource Settings’ has raised the opportunity to improve cooperation between major organizations. Jointly they can make a stronger impact on redressing the disparity in global access to surgical care.

References

- Debas HT, Gosselin R. Mccord C. Chapter 67 Surgery. In: Disease control priorities in developing countries, 2nd ed Oxford University Press, New York. 2006. p. 1245-60.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guid-ing Policy. Seattle, WA: IHME, 2013. Vasa. 2013. Available from: http://medcontent.metapress.com/index/A65RM03P4874243N.pdf

- Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strat-egy based on available data. Lancet 2008;372(9633):139-44.

- Groen RS, Samai M, Stewart K-A et al. Untreated surgical conditions in Sierra Leone: a cluster randomised, cross-sectional, countrywide survey. Lancet 2012;380 (9847):1082-7.

- Petroze RT, Groen RS, Niyonkuru F et al. Estimating operative disease preva-lence in a low-income country: results of a nationwide population survey in Rwanda. Surgery 2013;153(4):457-64.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA the WB and the UNPD. Trends in maternal mortal-ity: 1990 to 2013. Available from: www.unfpa.org/public/home/publications/pid/17448

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2005 – make every mother and child count.

- Peden M, McGee K, Krug E. Injury: a leading cause of the global burden of disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. World Health Or-ganization; 2002. Available from: www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/other_injury/chartb/en/

- Chao TE, Sharma K, Mandigo M et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery and its policy implications for global health: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Heal 2014;2(6):2334-2345.

- Gosselin RA, Heitto M. Cost-effective-ness of a district trauma hospital in Battambang, Cambodia. World J Surg 2008;32(11):2450-3.

- CapaCare, Medical education and training to increase the number of skilled staff at district hospitals. [cited 2014 Jun 22]. Available from: http://capacare.org/

- Bickler SW, Spiegel D. Improving surgi-cal care in low- and middle-income countries: a pivotal role for the World Health Organization. World J Surg. 2010;34(3):386-90.

- Chirdan LB, Ameh EA. Untreated sur-gical conditions: time for global action. Lancet 2012;380(9847):1040-1.

- http://www.thelancet.com/commissions/global-surgery, cited 2014 Aug 26.

- ICES International Collaboration for Essential Surgery. [cited 2014 Jun 15]. Available from: http://essentialsurgery.com/

- Opleiding IGT (2014) nvtg.org/index.php?id=1090

- Home – KIT KIT (2014), http://www.kit.nl/kit/en/