Main content

One of the key speakers at the NVTG conference ‘Human Resources, Research and Rights: Ethical dilemmas in Global Health’ this coming November is Ann Phoya, who originally trained as a midwife, later received a PhD, and for many years worked to improve Malawi’s health care system. One of our editors, Andrea van Meurs, spoke with her about trends in Malawi and what she considers the biggest challenges in maternal and child health.

| Biography Ann Maureen Phoya (PhD, Public Health Nurse, and Registered Nurse Midwife) started her career working as a midwife in Lilongwe, Malawi. She encountered the problems women face in labour and combined her midwifery experience with an advisory role in maternal health programs. Five years ago she retired from working at the Ministry of Health where she had served in various positions, as Director of the Sector-Wide Approach, Director of Nursing and Midwifery Services, and Safe Motherhood and Family Planning programme manager. After her retirement, Dr Phoya joined the University of North Carolina (UNC) Malawi Program where she served as Director for Safe Motherhood Projects funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The project sought to address the major causes of maternal mortality in Malawi. |

Currently she is the President of the Midwives Association of Malawi and working as Clinical Director at The Organized Network of Services for Everyone’s (ONSE) Health Activity. ONSE is the USAID Malawi’s flagship program for health. As President of the Midwives Association, she plays an advocacy role for midwives among health sector players including the government. Their aim is to ensure access to quality maternal and child health services, including family planning, as a strategy for reducing maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. Their overarching goal is to accelerate Malawian governmental efforts towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2030.

Maternal health in malawi

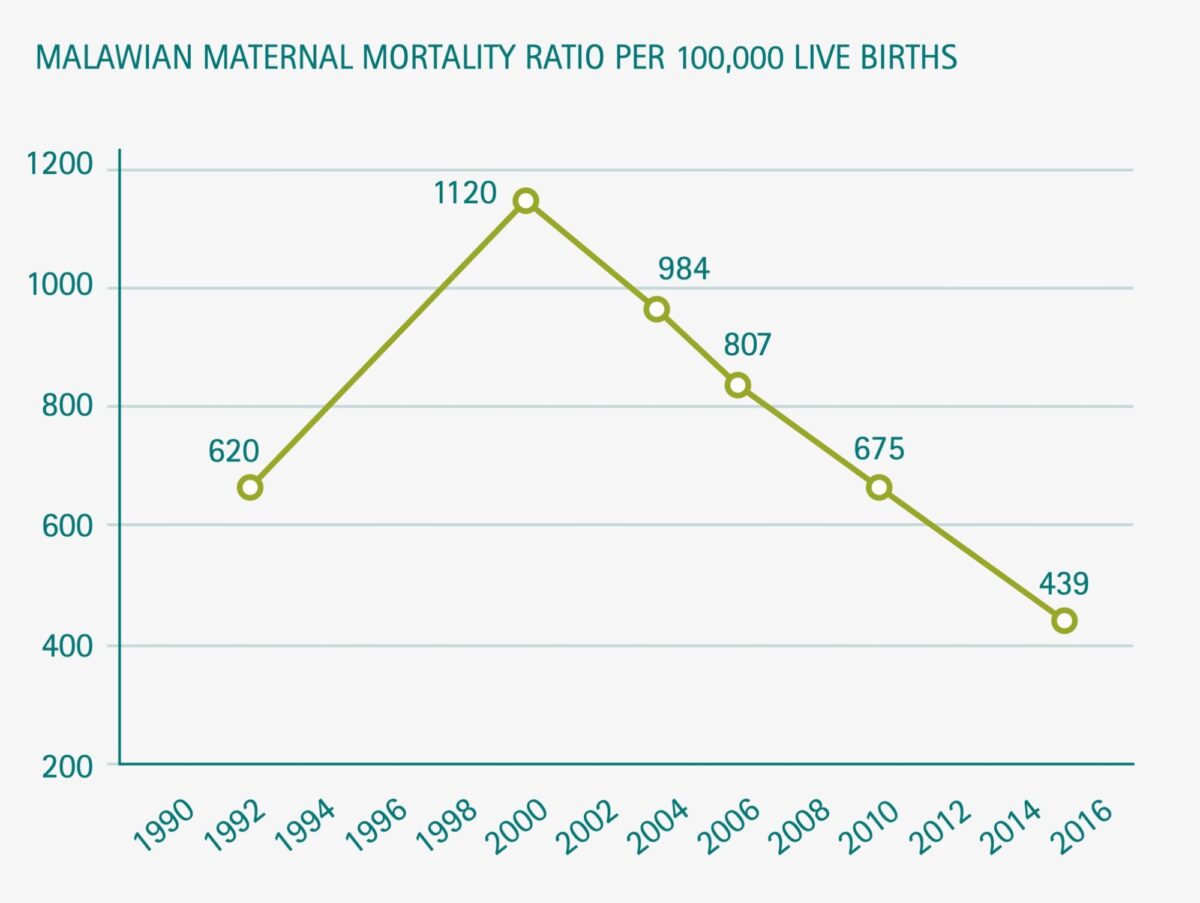

Globally, maternal mortality has significantly declined in the past two decades. In Malawi, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) declined from 1120 per 100,000 live births in 2004 to 439 per 100,000 live births in 2015. [2] Despite this improvement, Malawi’s MMR is still one of the highest in the world, and to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5A (75% reduction of MMR) in 2015, a steeper reduction down to an MMR of 155 per 100,000 live births would have been required. [3] Today, a 15-year-old Malawian girl has a one in 29 lifetime chance that she will eventually die from a pregnancy-related condition. [4] Maternal deaths account for 16% of all deaths to women aged 15-49.[2]

Source: Malawian Demographic Health Survey 1992, 2000, 2004, 2010 and 2015-2016.[2] Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is defined as the annual number of female deaths per 100,000 live births from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy (excluding accidental or incidental causes). Nota bene. The strong increase in MMR from 1992 to 2000 is thought to be due to the AIDS epidemic.

Reflecting on these trends, Dr Phoya comments: ‘Since 1990 a combination of efforts have contributed to the decrease in maternal mortality in Malawi. It started with important political commitments. First of all, traditional birth attendants were forbidden to help women deliver at home, because when a complication occurred they were not able to manage it. Moreover, the government pays for antenatal care and hospital care during labour and after delivery. A further important contributing factor is that the government has invested in improving the training programme of midwives. Midwives are adequately trained nowadays to manage the major killers, such as post-partum haemorrhage, complications of abortion, uterine infections, pregnancy induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia.’

Despite these improvements, even bigger challenges remain. ‘I saw the difficulties women faced to reach the hospital; the ambulance did not come in time, or it was in time, but then there was not enough fuel because the budget of the district hospital was too low.’ Also, there is still a severe shortage of midwives in Malawi. ‘The government trains as many midwives as possible, but as the population of Malawi is growing fast, there is still a shortage. Sometime so many deliveries take place at the same time that there are not enough professionals, delivery beds and supplies for all the women.’

Today, a 15-year-old malawian girl has a one in 29 lifetime chance that she will eventually die from a pregnancy-related condition.

Improvements are required at all levels of the health system

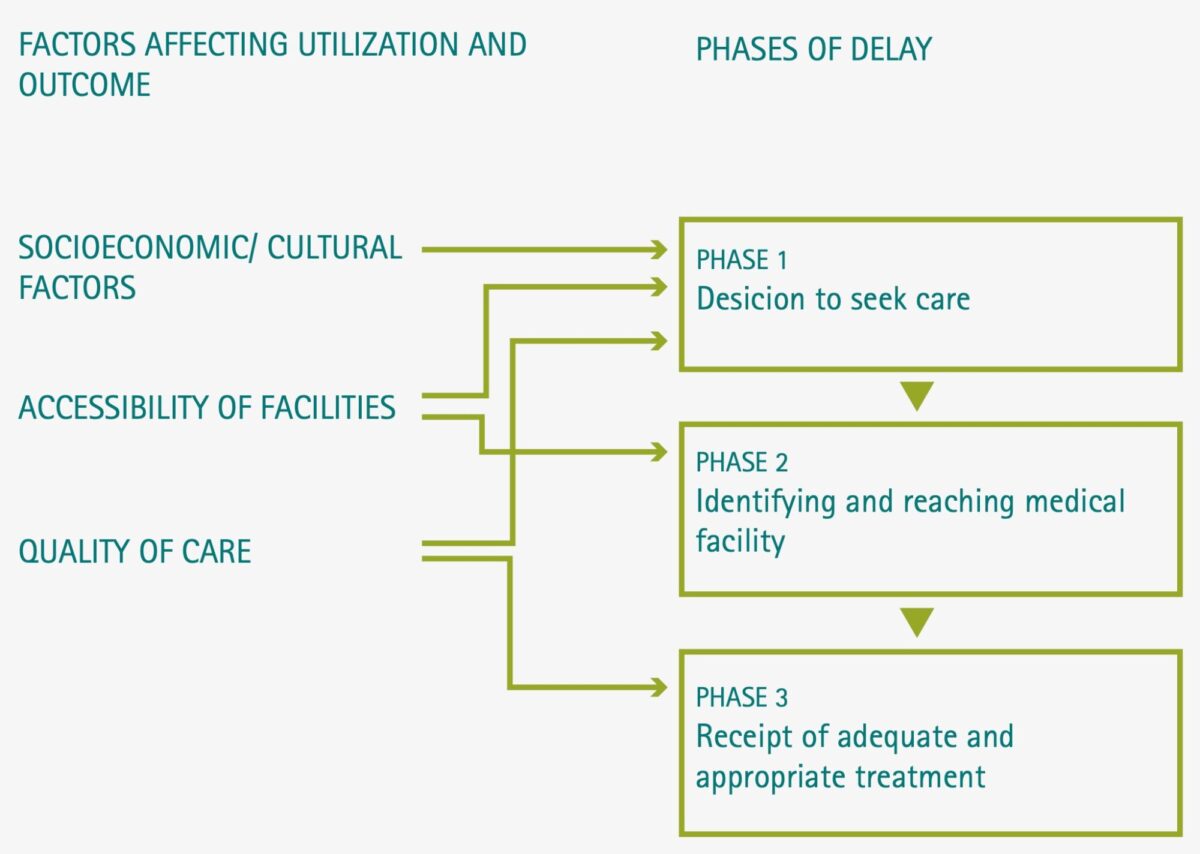

Dr Phoya makes it clear that efforts to reduce maternal mortality should tackle the whole health system. Earlier she worked together with the United Nations Safe Motherhood Initiative, designing strategies to avoid all three types of delay that are associated with high maternal mortality: 1. Delay at the level of the household in recognizing problems and in deciding to seek care, 2. Delay on the part of communities in providing transport for a parturient woman to get to a health facility, and 3. Delay on the part of health professionals within the health facility in providing appropriate care according to the woman’s needs (Figure 2). ‘If you address just one problem, you will encounter the next one. So to make a difference, you always have to reduce all three types of delay.’ She highlights one part of the project. ‘We started with an intervention at community level. By providing knowledge to the community, families were able to make a timely decision to utilize health service when help was needed. Women were provided with information during their antenatal period on what is normal in pregnancy, danger signs of pregnancy and delivery, and where to go for help.’ The project also addressed the second source of delay, transport. ‘We looked at the effectiveness of the utilization of ambulances. In addition, maternity waiting homes were built where mothers came to the facility and waited until labour started.’ One of the most important interventions they made was within the health system itself. Dr Phoya and her team trained the health workers to identify and manage complications, and they improved the provision of equipment and supplies. ‘To achieve real improvement, one has to look at the entire problem chain.’

Clandestine and unsafe abortion in malawi

One of the major causes of maternal mortality is unsafe abortion. It is estimated that 6-18% of maternal deaths are the result of complications after unsafe abortion. Each year 141,000 Malawian women have abortion, more than half of them clandestine. [3] A staggering 60% of all these abortions result in complications that need medical treatment. Restrictive abortion laws do not stop abortion from occurring, they just drive it underground, forcing women to resort to unsafe procedures. Unsafe abortion is an urgent public health priority in Malawi, which the government tries to manage since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. [5] That same year, a Special Law Commission was installed by the Malawian Government to review the restrictive abortion law.

Dr Phoya was one of the team members of the Commission. ‘The recommendation of the Special Law Commission was not to totally legalize abortions, but to define the conditions under which women can obtain an abortion: allow legal abortion for a woman’s physical or mental health, pregnancies resulting from incest or rape, and pregnancies of foetuses with severe malformation. If adopted, this would be a significant step forward to reduce maternal mortality.’

The recommended Malawi’s Termination of Pregnancy Bill has now been awaiting approval for two years. ‘Abortion is controversial in Malawi. Up to 80-90% of the population is Christian, and the church rejects abortion irrespective of the circumstances. The Commission took into consideration that Malawi is a Christian country but also acknowledged the harsh events that women may encounter which can be life threatening.’

Helping Malawian women to avoid unintended pregnancy is critical to reduce the incidence of abortion and possible complications and deaths. ‘We also very strongly recommend family planning programs, so that unintended pregnancies can be prevented.’ Research from 2015 shows that more than half of all pregnancies in Malawi were unintended, and almost one-third of those unintended pregnancies ended in abortion. ‘The goal is not for more women to have abortion, but for those who need it to have services available for safe abortion.’

Leadership

Ongoing research shows that leadership is one of the key health systems factors affecting the performance of maternal health services at facility level. Good leadership is essential for effective health systems development. [6] Dr Phoya agrees. ‘But, unfortunately reproductive and maternal health staff in Malawi are not trained to manage a health facility. They need better managerial skills to provide more effective and efficient health services.’ So, which important leadership characteristics can make a change? ‘We need people who can lead others, people who know what challenges are involved in providing the necessary services, people who can organize teams and sit together with them, and people who know what possible solutions in health care are available. A good leader can advocate for resources.’ These characteristics are not learned during a busy working day; they need to be trained. ‘A health provider needs to balance clinical and technical skills with leadership skills.’ As an advocate for quality maternal and child care, Dr Phoya recommends that midwifery training should contain different skill sets (technical, clinical and leadership skills) to ensure the availability of midwifery managers who can also lead others. ‘Moreover, our training should include training in an open feedback culture. We need to brief each other that this is the way we would like to do business, and that feedback is not intended to discourage but to encourage each other.’

Tips and tricks for foreign medical doctors working in malawi

Malawi has a very low health professionals population ratio of I healthcare worker for every 8,300 people (totalling doctors, clinical officers and medical assistants).[7]

‘The day that Malawi will have enough of its own medical doctors will not come soon, so there is enough room for foreign doctors to work in Malawi. My advice for young medical doctors who come to our country is to first carefully look and learn what the local people do and become a little bit more aware, because Malawi has a different culture. Work as a team, and decide together where and how you want to support each other. Moreover, learn how feedback is best provided.’

‘Before you start working, read as much as possible about Malawian culture. Then you will not be amazed why people are doing the things they do. Take time to learn and understand. Then you will be able to cope. But you should also know that you are working in an environment where you do not have all the resources that you normally have in Europe. You have to improvise. We have shortages of supplies and staff. At first that will be a shock, but eventually you will learn. But most important of all, create a solution that will be sustainable after you leave.’

Restrictive abortion laws do not stop abortion from occurring, they just drive it underground, forcing women to resort to unsafe procedures.

References

- https://www.msh.org/our-work/projects/organized-network-of-services-for-everyones-health-activity

- https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf

- Colbourn T, Lewycka S, Nambiar B, Anwar I, Phoya A, Mhango C. Maternal mortality in Malawi, 1977-2012. BMJ Open 2013;3:

- Guttmacher: https://www.guttmacher.org/news-release/2017/clandestine-and-unsafe-abortion-common-malawi

- https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3

- Mathole T, Lembani M, Jackson D, Zarowsky C, Bijlmakers L, Sanders D. Leadership and the functioning of maternal health services in two rural district hospitals in South Africa. Health Policy and Planning, 33, 2018, ii5-1115

- https://africacheck.org/reports/does-malawi-have-just-300-doctors-for-16-million-people/