Main content

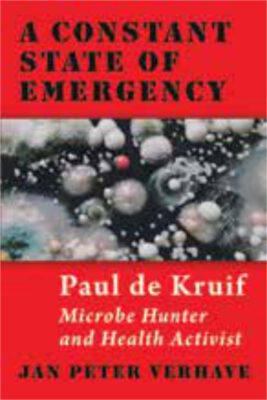

Paul de Kruif, microbe hunter and health activist

By Jan Peter Verhave

Van Raalte Press

ISBN-10: 1950572064;

ISBN-13: 978-1950572069

2020, 678 pages

How apt, this title for the biography of Paul de Kruif – microbiologist, journalist, and health activist. Apt, considering the current Covid-19 pandemic sweeping across the world. Also, De Kruif seemed to be in a constant state of emergency himself, considering the rapid speed at which he produced articles and books on medicine and science, his political swinging from progressive during the Great Depression, to eventually more conservative, leaving behind his (in those times) more radical views on socialized medicine and compulsory health insurance. Also, in his final years he converted back to religion, after being a lifelong atheist although born into a conservative Calvinist family in Zeeland, Michigan (USA).

There is no statue for this remarkable person, though one could consider Jan-Peter Verhave’s biography as such. The bulky book reads as a tribute to this man who seemed to be overlooked by (medical) historians and policy makers, although some may remember Paul de Kruif (1890-1971) as the author of the Microbe Hunters (1926), the book that became an international bestseller, translated into eighteen languages and is still in reprint. Enthusiasts described Microbe Hunters as a most exciting book ‘dealing with villains and heroes, blood and thunder’, and as a ‘war upon pathogenic organisms coming out of the laboratory’. These descriptions make you want to pick up a copy of this book, especially now that the Covid-19 pandemic has many scientists working against the clock to unravel the pathogenic effects of SARS-CoV-2. As in the early decades of the twentieth century, it is a very challenging and arduous task to develop a safe and effective vaccine. De Kruif brought the pioneers of microbiology and biomedicine, and their discoveries of cures for various infectious diseases to life by telling the fascinating story of the microbes and scientists involved in language everyone could understand.

With this book, the promising microbiologist definitely changed his career path by trading the laboratory for his typewriter. No more experiments, as when in the context of a study on the agents of influenza and the common cold he volunteered to shut himself up naked in an icebox for an hour day after day. Gradually he became a household name and, as a star reporter for The Reader’s Digest and other magazines, he was able to reach large audiences with his popular writings on medical discoveries, new drugs, causes and cures of diseases, vitamins and hormones, and health insurance. He did so much to the appreciation of the general public, but to a lesser extent of the medical professionals, who rejected him as someone writing about medical matters ‘while not even being a medical doctor’, expressing their fear that public health systems would take away their patients (and their fees).

Verhave’s book is a treat, as it took me on a journey learning about his lifelong mission to popularize medicine and educate people, and getting to know the person behind this public health advocate for policies that take into account the social determinants of health. To do so, he had to leave the “ivory tower” of science, using his typewriter as ‘a weapon against medical abuses and a fist to bounce the table’. And it bounced. He rallied the public against tuberculosis in Detroit, unsilenced “the big S” of syphilis (a condition that had become highly prevalent during the economic crisis in the 1920s with one out of ten Americans infected), and steering polio eradication. His quest resulted in more than 200 articles on the common health problems of his time: the dangers of raw milk, maternal deaths, childbed fever, diabetes, parrot fever, health insurance, and the deplorable health situation in Midwestern states and city slums.

Ingeniously, Jan Peter Verhave interweaves Paul de Kruif’s work as a catalyst for change with a quite detailed account of his personal life, his flamboyant life style, and his friendship with famous writers, including the poet Ezra Pound, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, and Sinclair Lewis, with whom he wrote Arrowsmith – a novel about a young medical doctor who gradually diverges from caring for patients to focusing on public health and controlling disease outbreaks. As a “champion for the poor” he was on speaking terms with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and a close friend of Vice-President Henry Wallace and Surgeon General Thomas Parran.

In many ways, he was ahead of his time, as De Kruif fully understood the public benefit of disseminating his work using mass media like theatre, film, radio, and even the new medium of the 1930s, comic books. The staging of one of his plays Yellow Jack in the Netherlands in 1934 impressed the audience, though considered a dicey experiment of bringing science to the stage. The play was based on a chapter in Microbe Hunters on the tragic death of yellow fever researchers dying in Cuba from experimental exposure to infective mosquitos.

Six hundred words are not enough to cover the wealth of information Verhave presents us in the more than 600 pages of a biography of ‘a hard-drinking womanizer with a blasphemous tongue’, as Verhave describes De Kruif in his foreword. For Verhave, retired biologist and parasitologist (and author of The Moses of Malaria (2011), a biography of the parasitologist Schwellengrebel), it was clear that the man who fought against poverty and horrible diseases deserved more attention. He definitely succeeded in placing De Kruif in the spotlight by taking us along ‘a medical history, a history of taking risks in moving doctors, scientists and lay people toward each other and toward a commonly shared healthcare system’. A story to note and to learn from.