Main content

Cancer is the second leading cause of death globally and responsible for 9.6 million deaths in 2018. The majority of these deaths, a staggering 70%, occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).[1] The total cancer burden is currently mainly dominant in high-income countries, which have an incidence rate of generally 2- to 3-fold higher than in LMICs. However, LMICs are quickly closing this gap. Africa for instance, is expected to have a 70% increase of newly diagnosed cancers by 2030.[2,3]

Surgery plays a vital role in the treatment of cancer. Since the establishment of the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery in 2013, more attention has been focused on improving the development and delivery of surgical and anaesthesia care in LMICs. However, surgical care for cancer is still lagging far behind, as it has not received sufficient attention in cancer control discussions, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).[4]

This paper aims to give a brief overview of the burden of cancer, the development of cancer services, and the role of surgery in SSA for patients with an oncological diagnosis.

The epidemiology of cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa

The GLOBOCAN database shows an estimated 1.1 million new cancer cases and about 700,000 deaths in 2020 in Africa.[5] These numbers may look surmountable compared to other continents, but it is only an estimate. As most health systems in African countries are not developed for cancer surveillance, the actual burden is likely to be higher, and with ongoing urbanisation and associated lifestyle changes it is even likely that the total increase might be greater than the expected 70% between 2012 and 2030.[6] This has mainly to do with the demographic transition which changes the population composition – expected increased life-expectancy in LMICs – and the prevalence of risk factors for cancer: people in societies in social and economic transition are more frequently exposed to risk factors linked to cancer such as smoking, obesity and alcohol consumption.[7]

It is bad to have cancer, but even worse to have cancer in Africa. The case fatality rate for cancers in Africa is 65% compared to 44% in a developed continent such as Europe, and almost all of those deaths occur at a young age.[3.7] Leading factors causing this are the absence of prevention and screening, late diagnosis, and subsequent suboptimal treatment.

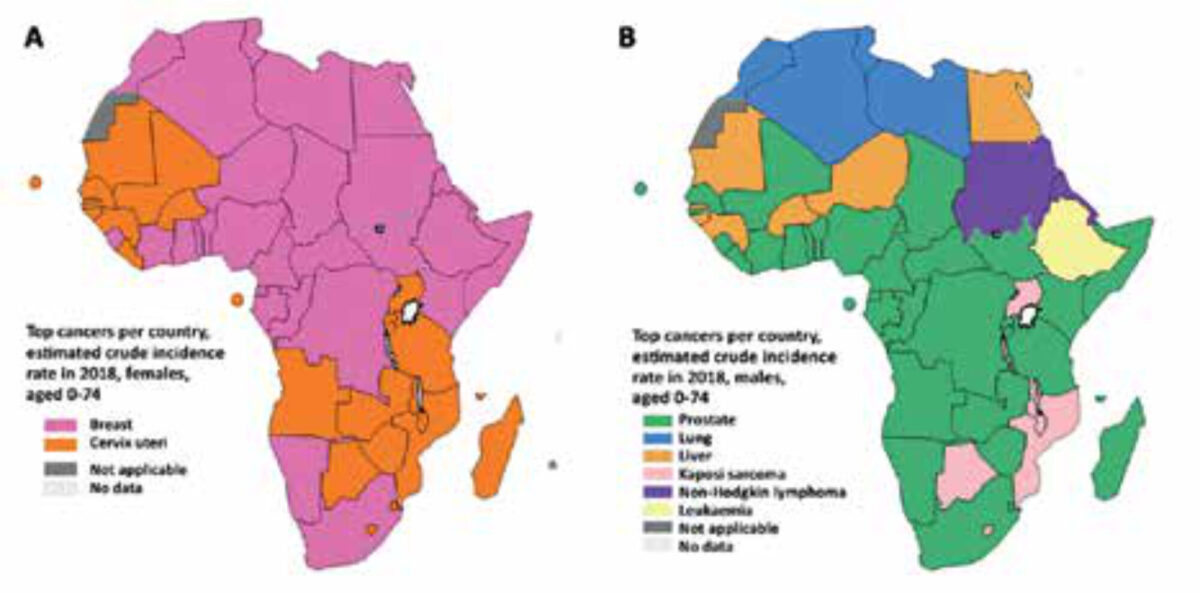

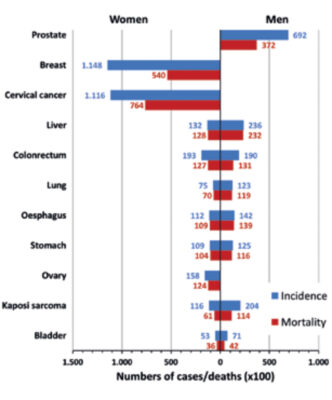

The most common types of cancers diagnosed and responsible for cancer mortality in Africa, especially in SSA, differ quite markedly from the rest of the world. For example, for women, cervical cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in SSA compared to breast cancer in the rest of the world. In men, lung cancer is the leading cause of death in most countries, although in SSA it is more heterogeneously divided between prostate, liver (still common despite hepatitis B vaccination), oesophagus cancer, and Kaposi’s sarcoma (Figure 1, 2).[3]

Between countries within SSA, the incidence rates of different types of cancer varies considerably, which has to do with aetiological factors: the environment e.g., climatic, dietary and microbiological (e.g. schistosomiasis for bladder cancer and Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer) factors – and genetics. It is likely that the incidence of cancers within those countries and the change in future are due to the demographic transition previously referred to.[8]

Health systems responsive to cancer detection and treatment

Prevention and screening strategies are the first principles of cancer control, whether in high- or low-income countries. These strategies are usually described in National Cancer Control Plans (NCCPs). The World Health Organization has formulated the most relevant for LMICs – tobacco control interventions, hepatitis B vaccination, human papillomavirus vaccination, and screening of precancerous cervical lesions – which are very cost-effective (slightly depending on the context). For the treatment of cancers, the most cost-effective are early-stage cervical cancer screening, treatment of early breast cancer, and highly curable childhood cancers (acute lymphoid leukaemia, Burkitt’s lymphoma, Wilms’ tumour, and retinoblastoma).[2] Palliative care is part of the essential package of cancer care as well.

However, the current availability of cancer screening and treatment services in LIMCs is poor. A recent literature review summarised the evidence on resources for cancer care in Africa.[9] A comprehensive list of all cancer treatment facilities contained 102 institutions, of which 38 were in South Africa. For radiotherapy services, it showed that 70% of the 277 radiotherapy machines in Africa are located in Egypt and South Africa. Twenty-nine countries had none. The availability of chemotherapy is low, and the price of such agents was 2.7-6.1 times the international reference price. Few health care workers are even trained to administer them. Technical and financial barriers prevent the widespread availability of radiotherapy machines and chemotherapeutics which are essential modalities for haematological cancers in particular.

The role of surgery in cancer care

Surgery is fundamental in all aspects of cancer care including biopsies for diagnosis, resections for treatment, and procedures for palliation.[10] In the treatment of the cancers most prevalent in SSA, surgery has the potential to play a key role. In more advanced settings, surgery is important in combination with radiotherapy and chemotherapy – e.g. breast conserving surgery with radiation. But in areas lacking radio- or chemotherapy, many cancers can be treated safely with relatively basic surgery and require only basic surgical instruments. For example, the modified radical mastectomy is still an appropriate treatment of local and regional disease in early-stage breast cancer. The operation is also technically not difficult and can be taught quite easily.[11] For cervical cancer, surgical treatment of stage I is usually curative.[12] Surgery is especially effective and also less complex and expensive when performed in early stage. Hence surgical cancer services should concomitantly be developed with services for early detection – especially in SSA where currently most patients present with advanced stages of disease. This sounds complex, but an example of basic, cost-effective requirements for cancer care that should be available throughout the levels of the delivery platform can been found in Table 1. Obviously, the delivery of surgical cancer services should coexist with other platforms delivering health services. For instance, the development of laboratory, pathology, and imaging services can synergistically improve a broader cluster of health services and make it more cost-effective.[2] Surgery plays a smaller role in advanced stages of cancer in LIMCs, but may still provide improved quality of life and add to palliative care. For example, a palliative colostomy in malignant bowel obstruction can improve quality of life in a palliative setting.[2]

Long term cancer control plans are needed

Currently a total of twelve countries (24%) in SSA have an NCCP.[13] An NCCP is crucial in the development of cancer services in LMICs and comprehensively defines the purpose of planned activity, the content of interventions, and the resources to execute the plan. As such, it provides guidance for infrastructure and human resource development. An NCCP should preferably be developed within a wider public sector strategy, adapted to local epidemiology and context, based on local data and evidence.[14] Such data can best be provided by national population-based cancer registries, but at the moment too few of these exist in Africa. The African Cancer Registry Network uses 31 registries in 22 countries, but only a few of these are national registries.

Next, governments are called upon to significantly put energy and time into oncological training and education. Surgical oncology requires a specific knowledge base and way of thinking, as well as training to develop particular surgical skills. Basic programmes could be set up for (non-physician) clinicians – e.g. clinical officers – which can be supported with distance consultation during clinical practice. More advanced programmes are suitable for registrars and specialists.[15] They should be adapted to the local context and ideally be embedded in existing training programmes. The College of Surgeons East, Central, and Southern Africa (COSECSA), for example, has embedded surgical oncology in the FCS (Fellowship of the College of Surgeons) general surgery curriculum.

| Community health centre | First-level hospital (district) | Second-level hospital (regional) | Third-level hospital (tertiary) |

|---|---|---|---|

| community health centre or small rural health hospital may have a small no. of inpatient and maternity beds capable of performing minor surgery under local anaesthesia paramedical staff, nurses, midwives visiting doctors | district- or provincial-hospital, with 50-300 beds adequately equipped major and minor operating theatres trained nonphysician or medical officer anaesthetists district medical officers in surgery, senior clinical officers in surgery, nurses, midwives +/- resident general surgeon and/or obstetrician-gynaecologist visiting specialists | referral-hospital of 200-800 beds well-equipped major and minor operating theatres supported by imaging, laboratory, and blood bank services, as well as basic ICU facilities general surgeons, obstetricians-gynaecologists anaesthesiologists +/- specialist surgeons | referral-hospital of 300-1,500 beds well-equipped major and minor operating theatres advanced imaging, laboratory services ICU facilities highly specialized staff and technical equipment clinical services highly differentiated by function often have teaching activities |

Conclusion

The burden of oncologic disease is an emergent challenge for Sub-Saharan Africa. Oncologic surgery plays a key role in the multidisciplinary approach of prevention, diagnosis and treatment. National cancer control plans are the essential frameworks to improve cancer care. Training and education programmes should be an integral part of this.

References

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Cancer; 2021 Mar 3 [accessed 2021 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

- Gelbrand H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, et. al. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Volume 3. 3rd ed. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; 2015. 341 p.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33538338

- Meara JG, Greenberg SLM. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare and economic development. Surgery. 2015 May;157(5):834-5. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.009

- Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today [Internet]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020 [accessed 2021 Jan 12]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

- Parkin DM, Jemal A, Bray F et al. Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa, volume III [Internet]. Geneva: Union for international Cancer Control; 2019 [cited 2021 Jan 8]. 282 p. Available from: https://www.uicc.org/resources/cancer-sub-saharan-africa

- Steward BW, Wild CP. World cancer report 2014 [Internet]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014 [cited 2021 Jan 10]. 630 p. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Non-Series-Publications/World-Cancer-Reports/World-Cancer-Report-2014

- Sitas F, Parkin DM, Chirenje M, et al. Part II: Cancer in Indigenous Africans–causes and control. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Aug;9(8):786-95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70198-0

- Stefan DC. Cancer Care in Africa: an overview of resources. J Glob Oncol. 2015 Sep 23;1(1):30-6. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.000406

- Wiafe BA, Karekezi C, Jaklitsch MT, et al. Perspectives on surgical oncology in Africa. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jan;46(1):3-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.09.003

- Anderson BO, Yip CH, Smith RA, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries: overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative Global Summit 2007. Cancer. 2008 Oct 15;113(8 Suppl):2221-43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23844

- Sauvaget C, Fayette JM, Muwonge R, et al. Accuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid for cervical cancer screening. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011 Apr;113(1):14-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.10.012

- International Cancer Control Partnership [Internet]. Geneva: Union for International Cancer Control. National Plans; [accessed 2021 Jan 8] Available from: http://www.iccp-portal.org/map

- Sirohi B, Chalkidou K, Pramesh CS, et al. Developing institutions for cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries: from cancer units to comprehensive cancer centres. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug;19(8):e395-2406. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045 (18) 30342-5

- Janssen YF, van der Plas WY, Benjamens S, et al. Cancer in low and middle income countries – The same disease with a different face. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jan;46(1):1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.09.006