Main content

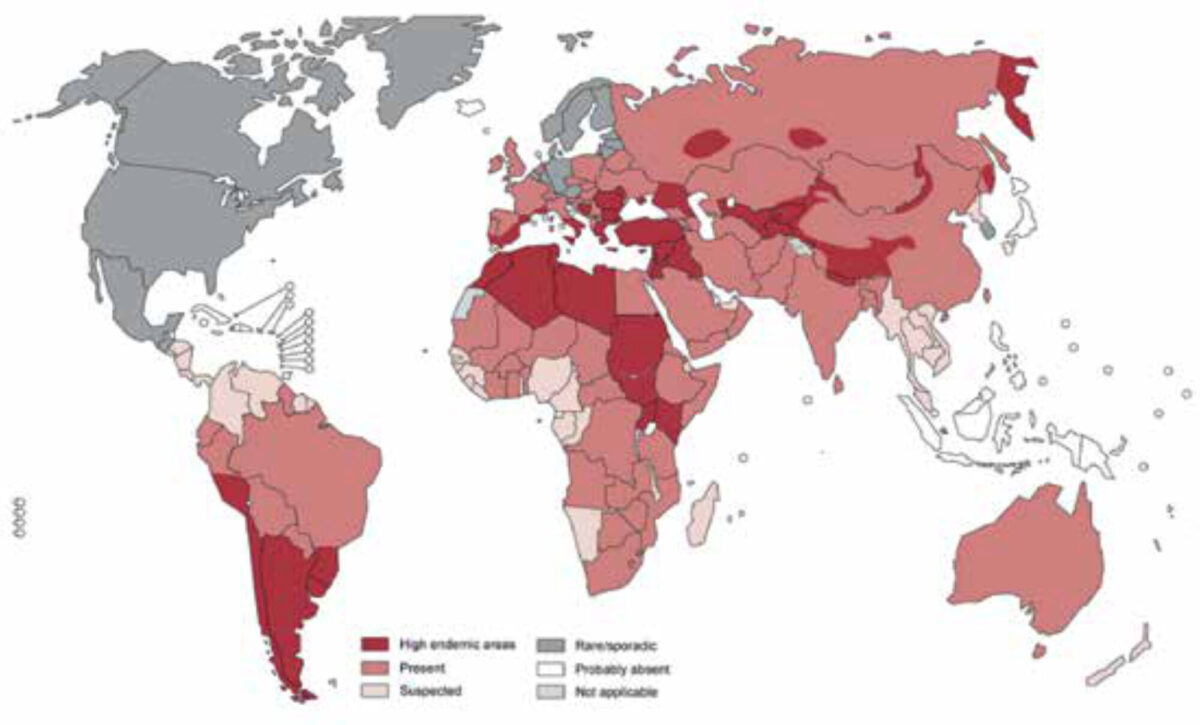

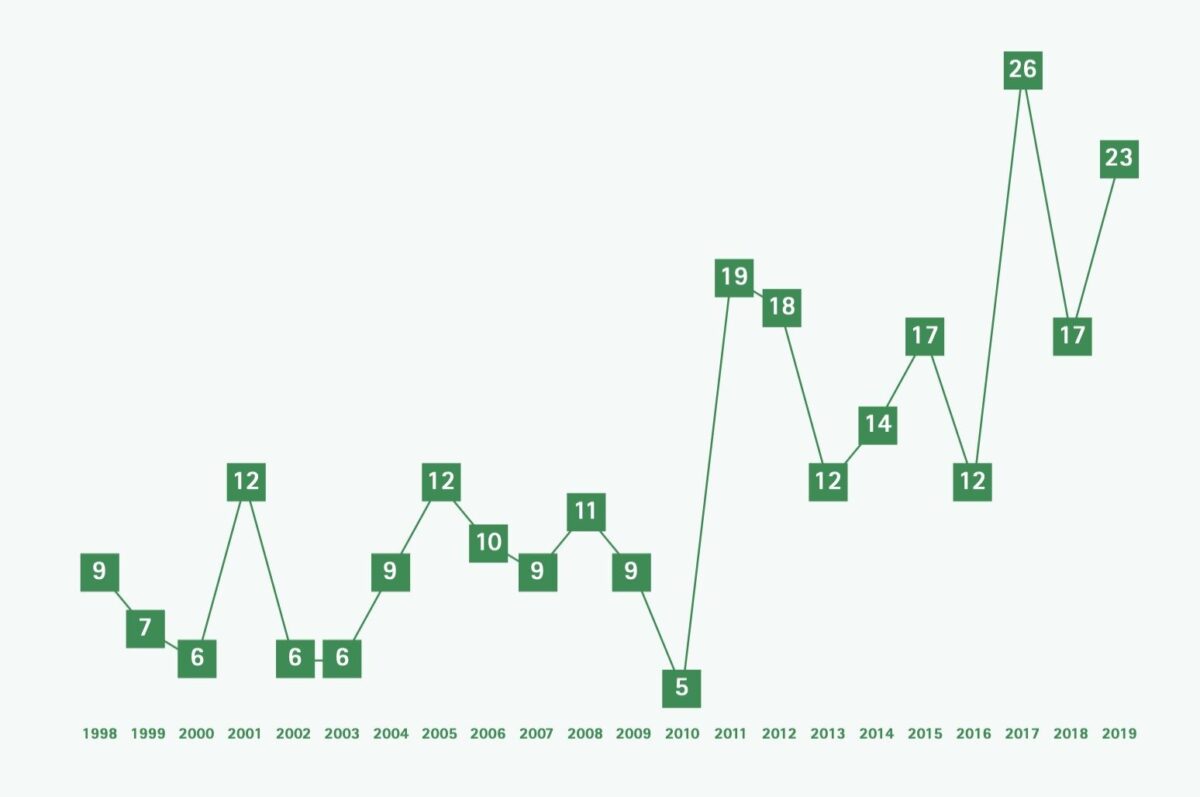

Echinococcosis is one of twenty neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) defined as such by the World Health Organization (WHO). In 2015, an estimated loss of 641,430 disability adjusted life years (DALYs) globally were reported, ranking the disease in the 12th place out of seventeen reported NTDs. [1] There are various endemic regions for echinococcosis worldwide where prevalence can reach up to 5-10% of the population, such as South America, North Africa and parts of the Middle East (Figure 1). [2] Although several attempts to control the disease have been made, it still remains a public health problem in numerous countries, with about two to three million cases worldwide and 19,300 deaths annually. [3,4] The prevalence depends on various factors such as education, economy, medical treatment and culture. In the Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), a centre of expertise for treatment of cystic echinococcosis (CE) in the Netherlands, an increase in new patients was seen in the last two decades among migrants, mainly from Morocco and Turkey and more recently also from Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Syria (Figure 2). There are two forms of echinococcosis in humans: cystic echinococcosis (CE), also called hydatidosis, and the alveolar form of echinococcosis. CE is a zoonosis caused by a tapeworm of the genus Echinococcosis granulosus. This article will focus on CE.

Pathogenesis

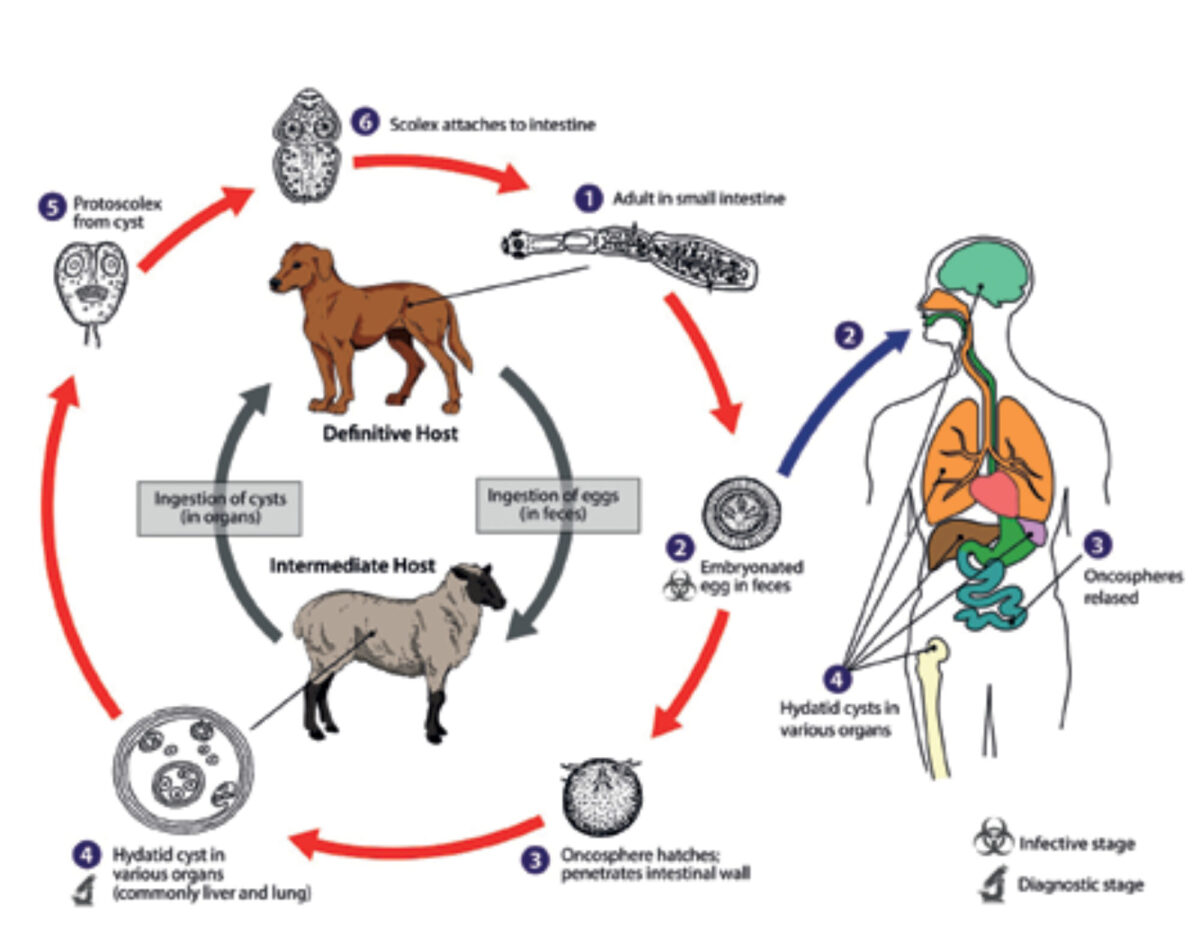

Human echinococcosis is caused by the larval stages of the Echinococcus tapeworm. Infection of humans occurs in a peculiar way and is not part of the natural cycle of the parasite. The normal intermediate host, cattle and other herbivores, are infected by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with eggs that develop into larvae in the viscera. The definitive host, usually dogs, are infected by eating the viscera of infected intermediate hosts. [5] The cycle is completed in the intestines of the definitive host as the larvae develop into mature tapeworms and produce eggs. [3] However, humans can become an accidental intermediate host, infected in the same way but not transmitting the disease to the definitive host. In the viscera of an intermediate host, the eggs hatch and hooked larvae (oncospheres) are released. They pass through the intestinal wall and enter the portal system, through which they colonize mainly the filtering organs such as liver and lungs. Here the oncospheres develop into larval echinococcal cysts. Most cysts are found in the liver (75%), with the majority of cysts localized in the right lobe (85%). Other affected organs include the lungs and the brain (Figure 3). The cyst steadily grows larger and infective protoscolices are produced inside the cyst. (4-8)

Clinical presentation

In 80% of cases, the cysts formed by the larvae are restricted to one organ and remain solitary in most patients. Besides lungs and liver, the cysts can sporadically occur in any other organ or tissue. [7,9] The majority of patients never develop symptoms and the disease remains clinically silent. It usually takes 5-20 years before the slowly growing cyst is large enough to cause symptoms. The most frequently seen clinical features are abdominal pain, usually in the right upper quadrant, hepatomegaly, hepatitis and/or cholangitis. [10] A serious complication is anaphylactic shock after rupture of a cyst. Other clinical presentations of patients are caused by pressure of the abdominal mass, on stomach, duodenum or biliary tree resulting in jaundice. [5]

Diagnosis

Because of the long asymptomatic period mentioned before, the diagnosis is often made coincidentally or when first complications occur, usually in adults. It is important to take the background of patients into account, focusing on visits to endemic regions or living in rural areas as well as living in close contact with definitive or intermediate hosts. Sometimes travellers to endemic countries can become infected by drinking water or eating undercooked food contaminated with eggs. Especially hikers, trekkers and hunters are at greater risk of coming into contact with infected animals or their stools.

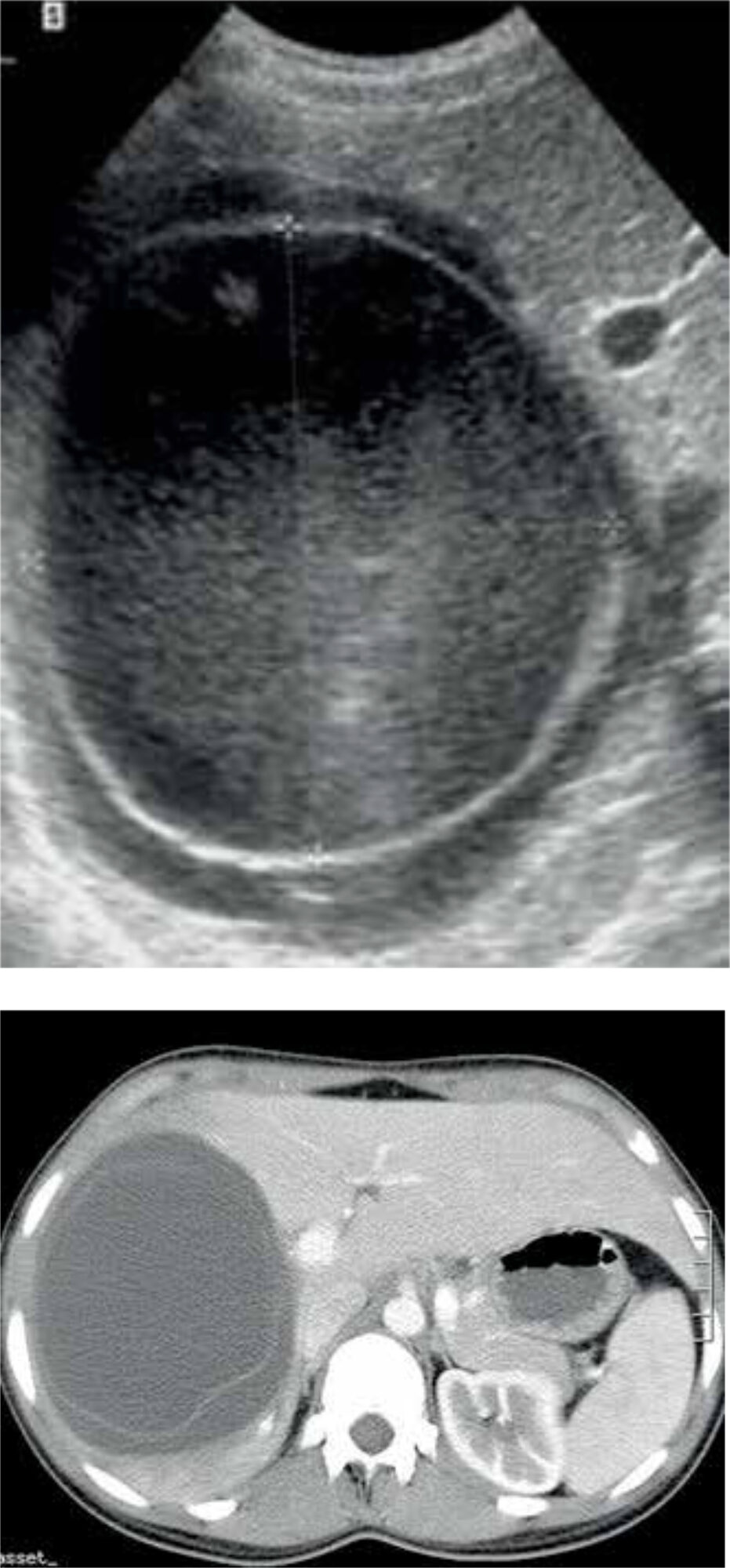

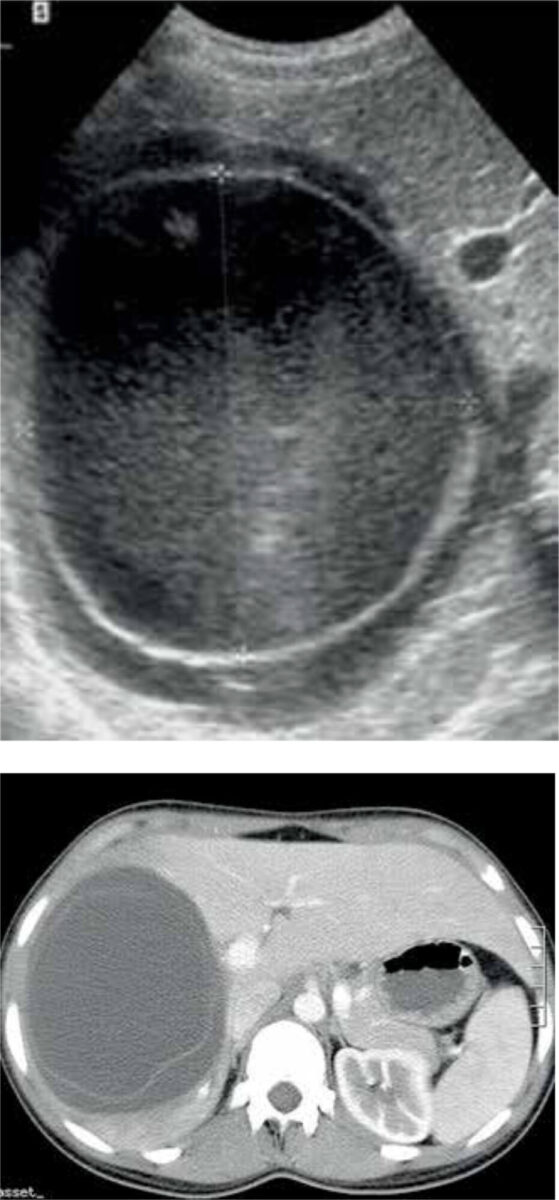

A combination of epidemiological and clinical findings, serological and immunological tests, and imaging is used to confirm the diagnosis of CE. Serology is helpful in detecting CE, but as a result of an undetectable immune response it misses about 30-40% of cases. Furthermore, many endemic countries lack the resources to use serology as a diagnostic tool. [11] Therefore, ultrasonic imaging is seen as the cornerstone in diagnosing CE. The accuracy is almost 90%, depending on the experience of the clinician. [12] Alternatively, a CT- or MRI-scan may be performed (Figure 4). [11]

Classification

Two classifications have been developed, based on ultrasound: the Gharbi and the WHO 2001 classification. The latter is a modification of the Gharbi classification made by the WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (WHO-IWGE); [13] it is recommended as the imaging reference standard, for guiding treatment and for use in follow-up (Table 1).

| CLASSIFICATION TYPE GHARBI ET AL. | WHO-IWGE | CLASSIFYING FEATURES | STAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | CE 1 | Univesicular fluid collection/simple cyst | Active |

| III | CE 2 | Multivesicular fluid collection with multiple daughter cysts or septae (honeycomb) | Active |

| II | CE 3 A | Fluid collection with membranes detached (water lily sign) | Transitional |

| III | CE 3 B | Daughter cysts in solid matrix | Transitional |

| IV | CE 4 | Cysts with heterogenous matrix, no daughter cysts | Inactive/degenerative |

| V | CE 5 | Solid cystic wall | Inactive/degenerative |

Treatment and control

Treatment should be given to all patients with vital cysts, as complications may be fatal or lead to morbidity with prolonged hospitalization. Furthermore, CE might pose a large social and economic burden on patients. Several treatment options are at hand: chemotherapy, surgery, percutaneous drainage and wait-and-see.

Chemotherapy consists of anthelmintic drugs, such as albendazole and mebendazole. It is mostly effective in the very early stages of uncomplicated CE and pre- and/or perioperatively, reducing the chance of dissemination and anaphylaxis. The surgical approach has long been the gold standard in treatment of CE and can consist of a conservative, radical, or laparoscopic technique. The PAIR technique (puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration) uses ultrasound to puncture the cyst, destruction of the protoscolices using a scolicidal fluid, and re-aspiration of this fluid after 15-20 minutes. PAIR is effective in early stages of the disease with clear cyst content (CE 2). At the Amsterdam UMC, a modified percutaneous technique was developed and frequently used, called PEVAC (percutaneous evacuation of cyst content). PEVAC may serve as a less invasive alternative to surgery in mature cysts (CE 3), reducing complications and hospital stay with a similar recurrence rate. [14] In an ongoing literature review, similar recurrence rates were found after percutaneous techniques vs. surgery in more mature cysts, while percutaneous techniques led to less complications and shorter hospital stay. This is in agreement with UMCA’s experience with percutaneous treatment of almost 300 CE patients over a period of more than twenty years (unpublished data). The last treatment option is the wait-and-see approach, usually in patients with CE 4 or CE 5 type cysts. [15] In various previously endemic countries, CE has been eliminated by implementing effective CE control strategies, primarily using a One Health approach. According to the WHO, the combination of deworming dogs, vaccination of lambs, and culling of older sheep could eliminate CE globally in less than ten years. However, as for many NTDs, data on CE are scarce. [4]

Conclusion

Cystic echinococcosis is one of the WHO’s twenty neglected diseases. In high-income countries, it is increasingly important as an imported disease in migrants and other travellers from endemic countries. In low- and middle-income countries, it may cause significant morbidity and mortality if left untreated, posing an important burden on local health facilities. CE is a typical example of how animal and human health are interrelated, underlining the One Health approach as recommended by the WHO.

References

- Mitra AK, Mawson AR. Neglected tropical diseases: epidemiology and global burden. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2017 Aug 5;2(3):36.

- Pakala T, Molina M, Wu GY. Hepatic echinococcal cysts: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016 Mar 28;4(1):39-46.

- Craig P, McManus D. Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007 Jun;35(6):385-94.

- World Health Organization. Echinococcosis. 2019 May 24. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/echinococcosis.

- Mandal S, Mandal MD. Human cystic echinococcosis: epidemiologic, zoonotic, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012 Apr;5(4):253-60.

- Yagci G, Ustunsoz B, Kaymakcioglu N, et al. Results of surgical, laparoscopic, and percutaneous treatment for hydatid disease of the liver: 10 years experience with 355 patients. World J Surg. 2012 Dec;29(12):1670-1679.

- Medscape. Echinococcosis hydatid cyst. Brunetti CF; Updated 2015 Dec 05. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/216432-overview#a5.

- CDC. Echinococcosis. Biology. 2012 [updated 2019 July 16]. Available from: https://www.cdcgov/parasites/echinococcosis/biology.html.

- Filippou D, Tselepis D, Filippou G. Advances in liver echinococcosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Feb;5(2):152-59.

- Mihmanli M, Idiz UO, Kaya C. Current status of diagnosis and treatment of hepatic echinococcosis. World J Hepatol. 2016 Oct 8;8(28):1169-81.

- Pakala T, Molina M, Wu GY. Hepatic echinococcal cysts: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016 Mar 28;4(1):39-46.

- Macpherson CNL, Milner R. Performance characteristics and quality control of community based ultrasound surveys for cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Acta Trop. 2003 Feb;85(2):203-9.

- WHO Informal Working Group. International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 2003 Feb;85(2):253-61.

- Shera TA, Choh NA, Gojwari TA. A comparison of imaging guided double percutaneous aspiration injection and surgery in the treatment of cystic echinococcosis of liver. Br J Radiol. 2017 Apr;90(1072). DOI:10.1259/bjr.20160640.

- Stojkovic MJ, Rosenberger KD, Steudle F, et al. Watch and wait management of inactive cystic echinococcosis – Does the path to inactivity matter – Analysis of a prospective patient cohort. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2016 Dec;10(12). DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005243.