Main content

Childhood mortality in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has dramatically decreased over the last two decades. [1,2] In the 1990s, nearly one in five children living in sub-Saharan Africa died before their fifth birthday. The under-five mortality for sub-Saharan Africa has since more than halved and is currently estimated at 7.6%.[1,2]

Childhood mortality in LMIC settings however remains an unacceptable eight times higher than in high-income country (HIC) settings and needs further reduction in the coming decades. [2] The question is of course how to achieve this. So far the largest reduction may have been due to preventive medicine, an area that may still have room for improvement. [3] However, we now may have entered an era where further reduction of mortality should (also) come from improved curative services.

Reducing in-hospital mortality means improving care of critically sick children, or in other words developing critical care medicine in low-income settings. The WHO acknowledged the importance of critical care in paediatrics by developing the Emergency Triage and Treatment (ETAT) guidelines in the previous decade. [4] These guidelines, developed for healthcare workers in LMICs, help to timely detect critically sick children, prioritise their care, and improve the quality of resuscitation and save lives. [5]

Although this may be seen as the introduction of critical care to LMIC, still much has to be improved in the care we deliver to children following the acute event. Focussing attention, resources, and efforts on the sickest children is ideally done in high-care wards or paediatric intensive care units (PICU), a concept which is relatively new to sub-Saharan Africa. Even in western settings, separate paediatric intensive care units were only established in the 70s and 80s. In sub-Saharan Africa, these units are not common but are slowly appearing. [6]

Setting

Malawi is one of the poorest African countries and has a current health expenditure of 30 US dollars per capita per year. [7] Blantyre, the second largest town in Malawi, is home to the country’s only medical university, the College of Medicine, which was founded in the early 1990s. The Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital is a third-line government hospital affiliated to the college. Its paediatric department is one of the largest departments and hosts on average 200-350 in-patients, with wards specialising in general paediatrics, neonatal care, malnutrition, oncology, orthopaedics, neurosurgery, burns and general paediatric surgery. [8] The paediatric surgical unit was rebuilt and re-opened in 2017 as the ‘Mercy James Centre for Paediatric Surgery and Intensive Care‘. As part of the improved care, three new operating theatres, a four-bed high-care and six-bed paediatric intensive care was included in the building plans for this new paediatric surgical hospital.

Challenges

Setting up a new high-tech facility in an LMIC faces several challenges. Some of these challenges may not be different from setting up a new health facility or even a business in a low-resource setting. However, the consequences of suboptimal functioning are potentially lethal as critically sick children are involved. Unmistakably the most important challenge has been obtaining funding, embedding it in the existing infrastructure, and obtaining sustainable involvement of the government. To achieve this, several important collaborations have contributed essential equipment and other resources to the development of our PICU (Figure 1). The paper focusses though on more practical challenges we faced during the first year.

Staff

Staffing the unit with sufficient and adequately trained nurses, doctors, and support staff is unmistakably one of the most important aspects in developing a PICU. In collaboration with the government, 20 nurses were hired to staff the six-bed PICU, a relatively low number compared to western PICUs in HICs, but a very high number compared to normal hospital wards in LMICs. Some of the nurses had paediatric experience whilst others were newly registered nurses. All nurses were trained in the weeks prior to opening the PICU with support from an American PICU nurse trainer, input from Cape Town University, and the involvement of the paediatric, surgical and aesthetic departments and the college of nursing. The two lead nurses of the unit had spent a six-month period in the PICU of Oslo and a Norwegian PICU nurse was present to deliver bedside training.

Since the opening, nurse training has continued on site, and after a year most nurses have developed from beginner to a good basic level of PICU nursing. In the next year, the level should be further improved to also be able to make an impact on the vulnerable neonates which require a very high level of attention to detail and care.

During the first year, new nurses joined our team, which emphasised the need of having our own PICU nurse trainers to deliver the curriculum developed for our new staff. Two nurse teachers were selected to receive further training in Oslo and have been linked up with American and Dutch nurse trainers. By involving the College of Nursing in Malawi, we aim to boost the development of a critical care curriculum for nurses in Malawi.

The unit is currently run by two international paediatric intensivists that perform the clinical work and build up the unit. With the help of visiting intensivists from the collaborative projects and a Malawian paediatric anaesthetist, the clinical work of the unit is covered. During out of office hours most of the work is performed by Anaesthetics Clinical Officers, who have been trained over the past 18 months in PICU-related topics. These physicians can rely on a growing number of local protocols developed over the past months which are accessible through a website. [9] In the long run, the unit should be staffed by a paediatric intensivist from Malawi; the first one is currently being trained in Cape Town, South Africa. A six-month fellowship in paediatric intensive care and anaesthesia was developed to encourage interest among young doctors.

The care for critically sick patients relies on many more persons than doctors and nurses alone, including ward assistants, cleaners, technicians, store managers, lab technicians, pharmacists, physiotherapists and data clerks. The performance of all these persons is essential but demands (very) different skills in the critical care setting and requires extra training. Most training, once again, was provided in the ward by our own staff or by external specialists who were sent by one of the collaborative partners, as many of these areas involve expertise that cannot be provided by nurses and doctors.

Consumables, drugs and logistics

The permanent availability of essential consumables and drugs is essential to outcomes of PICU patients. A list of essential equipment and drugs was compiled together with our management team, and we are setting up reliable supply lines and a solid store management system. This process in itself is quite complex in our settings for several reasons. We require new items and drugs that have not been routinely available in health services in Malawi. Some items cannot be bought locally and delivery can take weeks to months. We partly depend upon donations, which may not always provide the right items. We are trying to improve this essential aspect by simultaneously involving hospital pharmacies at a local and national level, preferably sourcing items through local commercial suppliers rather than depending upon international donations, by developing a computerised stock system, and by appointing a stores and procurement manager.

Equipment and facilities

Intensive care medicine involves a large quantity of essential equipment including ventilators, monitors, syringe drivers, special intensive care beds, mobile imaging machines and basic lab machines. These items were donated as refurbished equipment or purchased as new equipment with the help of donors. To be able to run these sensitive machines non-stop, several essential facilities were incorporated in the design of the hospital including a generator and Unlimited Power Supply (UPS), a plant to concentrate oxygen, air and create vacuum and a buffered water supply. These systems are all equipped with alarm units to detect malfunctioning and require permanently available staff to perform urgent repairs. Training and appointment of a qualified and motivated technician has been essential to keep the donated items running, and we aim to move towards preventive maintenance and an indexed system of equipment.

Hygiene

Intensive care also means clustering patients who are severely sick, often due to infections, with patients most vulnerable to infections. Infection prevention and treatment is therefore even more important than in other parts of the hospital. Even in high-income settings it is not uncommon that (multi-resistant) bacteria rapidly spread in ICUs and cause temporary closing of units. In our hospital, multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria were and are present and have not ignored our PICU. [10] The role of an active and multidisciplinary infection prevention committee, medical bacteriology support, appropriate antibiotic drugs / guidelines, and a proper supply line to prevent re-using equipment are essential but also a challenge.

Patients and ethics

Possibly the biggest clinical challenge is deciding whom to admit (or reject) to PICU. Even in settings with high resources this is a recurrent dilemma, but in settings with high numbers of severely sick children and limited beds this ethical dilemma is even more pressing. An important element of critical care is to focus resources on those in whom we can positively change the course of disease. Deferring a patient from PICU will likely mean the patient will not survive, whilst admission of a patient who will not survive indirectly means that (several) other children with a potentially good outcome may not get a PICU bed.

The decision is further complicated since a) PICU-care is new to all physicians involved and thus there is little experience and data aiding these decisions, b) presentations are often delayed, and c) information on the course and cause of disease is more difficult to obtain. The latter two both delay prompt and adequate treatment and reduce chances of full recovery. Ideally, intensive care is given to a healthy child suffering from an acute illness which is detected in time, and after a short and intensive treatment, the child fully recovers. The ICU is then a bridge towards a healthy future. We have written a guideline that can help in making these difficult decisions as we gather outcome data from patients we admit to PICU. [9]

The timing of admission is essential as detection of clinical deterioration and timely intervention and PICU admission can prevent morbidity and mortality. Creating a PICU has demonstrated the need for a unit that can more closely monitor patients who may need more intensive care or do not need to be in PICU anymore but still need monitoring. The paediatric department is currently developing such a high-care unit, which is essential to improve the full chain of care for our patients.

Current data

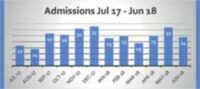

In the first year since opening, we admitted 296 patients to PICU who spent 1185 bed days in our unit. The number of admissions per month is displayed in Figure 2. Most admissions consisted of children with surgical conditions (80%). The majority of our patients (151/296 = 51.0%) was less than one year of age and 29.3% (n=87) less than one month. Newborns are generally overrepresented in PICUs, as this age group is commonly affected by either congenital (surgical) conditions or infectious diseases. The percentage of patients who were ventilated during admission increased from 40% in the first month to approximately 80% at the end of the year. The overall mortality was 25% (n=75), which was higher in neonates but was not different amongst surgical or medical patients (data not shown).

Future directions and conclusion

The development of a paediatric intensive care in Malawi has been a major achievement that was realised by the commitment and collaboration of many individuals, institutes and governmental and non-governmental bodies. Embedding the PICU into the current system and obtaining government and hospital support and resources has been essential. However, much more time and effort will be needed to fully embed the PICU in paediatric healthcare services. Challenges to be faced involve developing reliable supply lines and stocks, maintaining and replacing essential equipment, development of a critical care curriculum for nurses and doctors, and finally improvement of high-care facilities in our medical wards.

Critical care has brought a new dimension to paediatric healthcare in Malawi and has made a promising impact on the outcomes of several children. The opening of a PICU will boost these developments and will undoubtedly further improve paediatric healthcare and survival in Malawi and other sub-Saharan African countries.

Co-authors

P. WEIR, T. KAPALAMULA, E. THOMSON, S. CHIKUMBANJE, M. MPUNGA, S. DAYO AND E. BORGSTEIN; all from the Mercy James Centre for paediatric surgery and intensive care, Blantyre, Malawi.

Q. DUBE; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi.

G.K. BENTSEN; Division of emergencies and critical care, Oslo University Hospital, Norway.

References

- UNICEF 2018 https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/under-five-mortality/. [accessed 21-jan-2019].

- WHO 2018; https://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/mortality_un-der_five_text/en/. [accessed 21-jan-2019].

- WHO 2016; Health in 2015: from MDGs to SDGs; https://www.who.int/gho/publications/mdgs-sdgs/en/. [accessed 21-jan-2019].

- WHO 2015; Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) course; https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/docu-ments/9241546875/en/. [accessed 21-jan-2019].

- Kapoor R, Sandoval MA, Avendaño L, Cruz AT, Soto MA, Camp EA, Crouse HL. Regional scale-up of an Emergency Triage Assessment and Treat-ment (ETAT) training programme from a referral hospital to primary care health centres in Gua-temala. Emerg Med J. 2016 Sep;33(9):611-7.

- Punchak M, Hall K, Seni A, Buck WC, et al. Epidemiol-ogy of Disease and Mortality From a PICU in Mozam-bique Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov;19(11):e603-e610.

- WHO 2016, Country statistics for Malawi, http://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_pro-file/Index/en; accessed 21-jan-2019.

- Harris C, Mills R, Seager E, Blackstock S, et al. Paedi-atric deaths in a tertiary government hospital setting, Malawi. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2018 Nov 19:1-9.

- Protocols for the pediatric intensive care; www.mercyjames.info/picu. [accessed 21-jan-2019).

- Musicha P, Cornick JE, Bar-Zeev N, et al. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream in-fection isolates at a large urban hospital in Malawi (1998-2016): a surveillance study. Lan-cet Infect Dis. 2017 Oct;17(10):1042-1052.