Main content

The global condom manufacturing industry is highly concentrated. In the world of male condoms, there are thirteen leading manufacturers, supplying directly to the commercial market, to major condom brands, and to the tender market – comprising governments and NGOs. The female condom market, on the other hand, is quite different. Up to 2008, there was only one manufacturer of female condoms, the UK based Female Health Company which manufactures the FC2®female condom, the first to prequalify with WHO and UNFPA (in 2007) and now available in 143 countries. However, availability does not automatically imply access. Although prequalification paved the way for (donor) funding of the female condom, the demand and supply are still much lower compared to the male condom. Many women are still denied access to a commodity which is renowned for its dual protection against sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies. In this article we focus in particular on a partnership that was formed around female condoms, with a particular emphasis on the supply side, considering supply as a crucial element in ensuring universal access to the female condoms.

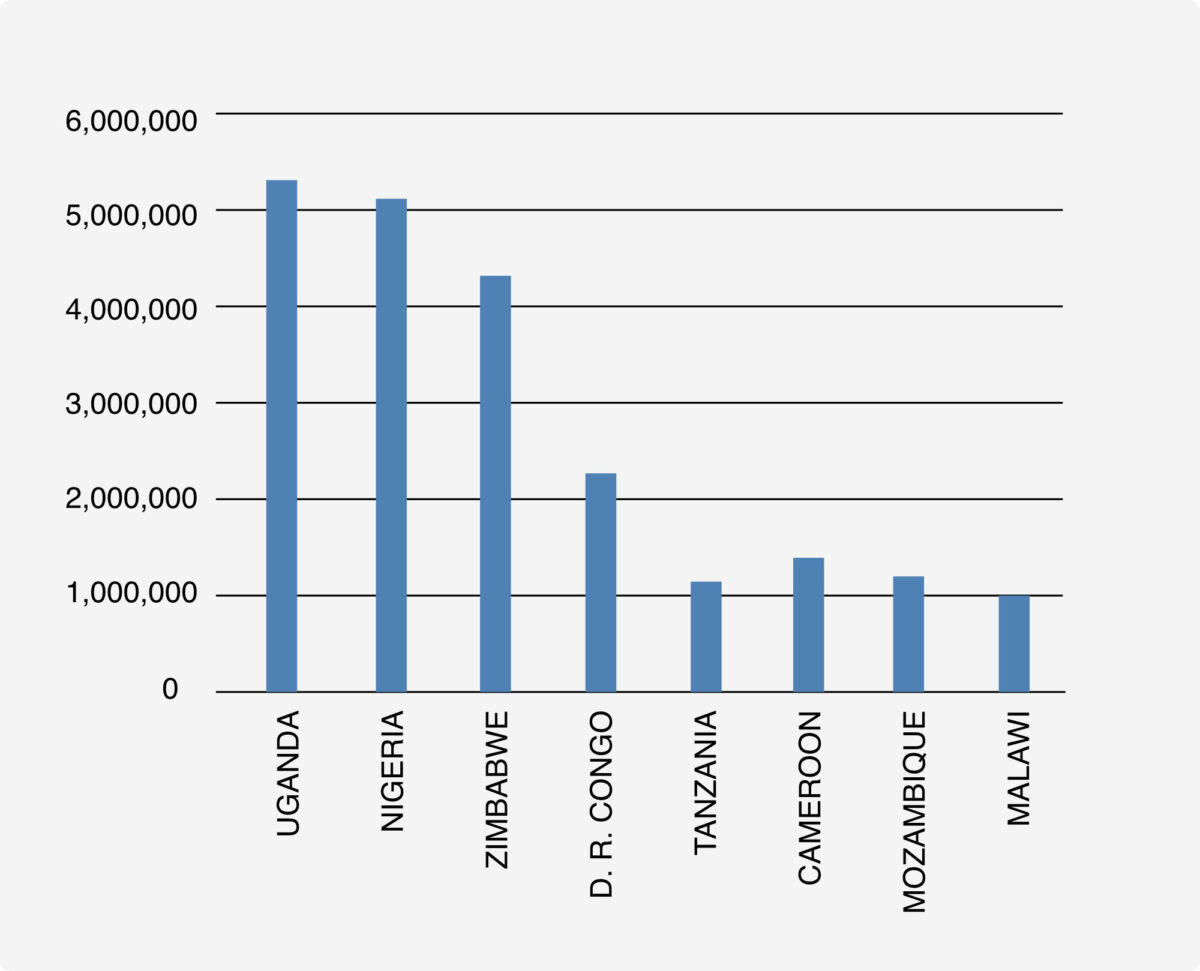

Source: Family Planning Market Report (2015), Clinton Health Access Initiative

Partnering for female condoms

Universal Access to Female Condoms (UAFC) is an initiative of four Dutch parties. The programme ran from 2008 to 2015 and was set up to stimulate the demand for and the supply of female condoms. What brought this partnership together was the strong conviction of the parties involved that more impulses were needed to firmly put female condoms on the donor community agenda to make them more widely available. As Peters et al. argue in the article ‘The international denial of a strong potential’, universal access is not primarily hampered by obstacles on the user side, but it is reluctance on the side of policy makers that has largely positioned the female condom in the market. The partnership therefore was formed with parties focusing on different aspects of making female condoms more widely available. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs proved to be a strategic ally in promoting female condoms among the donor community at international and national levels. Building on its experience in grant management, Oxfam Novib undertook a variety of activities to stimulate demand through its field offices. Rutgers brought to the partnership its expertise with Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR), including advocacy at national and international levels. i+solutions, an independent not-for-profit organization that is specialized in pharmaceutical supply chain management for low and middle income countries, worked with various partner countries to secure availability of female condoms. i+solutions also took care of the manufacturing and regulatory component of the programme, including procurement, quality assurance, technical assistance for manufacturers in regulatory issues, technical assistance in supply chain management, gathering market intelligence, and informing manufacturers about the WHO/UNFPA prequalification process.

Linking supply with increasing demand

The UAFC programme aimed to increase the variety of quality-assured and affordable female condoms on the market. This objective was founded on the premise that an increase in demand and variety of female condoms would arouse greater competition in the market, leading to a lower price and better affordability. Besides focusing on manufacturers and research institutions, the UAFC consortium also worked closely with in-country advocacy organizations and social marketing organizations, who in turn worked with local public and private distribution outlets and ministries of health. Three countries were selected for implementation, all for different reasons. In Nigeria, Oxfam Novib partners requested being selected because of the public sector failure with the implementation of previous female condom programmes. i+solutions worked with a social marketing organization in Cameroon, following a promising approach in demand creation – the hair-dresser saloon distribution model. In Mozambique, UAFC collaborated in the context of an already existing donor funded female condom programme.

| 2014 | 27,211,000 |

| 2013 | 49,722,000 |

| 2012 | 27,081,030 |

| 2011 | 21,879,000 |

As shown in Table 1 below, according to the Reproductive Health Interchange (RHI) overview, there was an overall increase in procurement volumes between 2011 and 2014, though global (donor) procurement fluctuates. [4] The stark decrease in 2014 is explained by the fact that a large amount was purchased in 2013 by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. It is normally the case that, after a country makes such a big purchase, no procurement will take place in the following 2 years.

These are conservative estimates, since not all procurement can be monitored by the RHI, as for example direct purchases from private parties or governments are not always registered. UNFPA is the biggest procurer (more than 13 million female condoms in 2014), supplying female condoms through their programmes with governments, other agencies and civil society organisations. UNFPA has been procuring contraceptives for more than 30 years and, as of today, remains the largest public sector procurer. Other actors include the USAID / Deliver Project (procured 11,049,000 in 2014) – which supplies commodities through various field projects on HIV/AIDS and the prevention of unwanted pregnancies. The Global Fund procures female condoms as part of their HIV/AIDS prevention strategies. IPPF also procures female condoms for use in their SRHR programmes – albeit in small quantities (48,000 in 2014). Though it would be unfair to compare the supply of female and male condoms, the statistics are staggering. In 2014, for every 37 male condoms, UNFPA procured 1 female condom (MC: 489 million and 13 million female condoms); in the case of USAID, the male-female procurement ratio is 83 to 1 (MC: 909 million and 11 million female condoms). [5]

A recent global market analysis shows the volumes of female condoms that are shipped to 69 countries that are enrolled in the Family Planning Initiative (FP2020). The countries with the highest volumes are shown in Figure 1 on page 10. [6]

Stimulating change

Gradually the interest in manufacturing female condoms has increased. In terms of volume, the Female Health Company still dominates the market. Since 2008 however, more private companies have shown interest in manufacturing female condoms, such as Cupid Ltd – which produces both male and female latex condoms, with a yearly capacity of 400 million male and 15-20 million female condoms. Others have followed suit, with some seven companies now manufacturing female condoms. The role of the partnership within the UAFC programme in stimulating these developments is hard to quantify. Nevertheless, in the context of UAFC, i+solutions provided technical assistance to manufacturers on regulatory issues and on FC registration requirements in different countries, built their capacities in good manufacturing practices, and launched a web-based market intelligence portal (through the FCMi portal). [7] UAFC has (co-) financed testing labs, is developing a manual for parallel programming, and has invested in a number of functionality studies. [8] Considering the slow entry of female condoms into the global market, an increased interest from manufacturers can be considered promising.

Lessons learned

Public health issues are better addressed through a holistic approach involving public-private partnerships. The UAFC initiative has stimulated the demand for and supply of female condoms. The partners in the consortium have different roles, each focusing on a different aspect of the female condom promotion, production and marketing process. A recent end-of-term evaluation demonstrated the benefits of this synergy and also how persistent bottlenecks in availability and use of female condoms can be tackled. Involving men in female condom promotion and use, a strategic change that was taken in the course of the programme, has paid off, as Koster et al have demonstrated in the male acceptance studies conducted in the context of UAFC. [9] The studies clearly show the benefits of involving men in SRHR issues, in particular in using female condoms for family planning or STI prevention. The technical expertise offered to manufacturers, local NGOs and social marketing organisations, and to some ministries of health, has enhanced the credibility of the consortium globally and at the country level. The neutrality of UAFC – not being attached to one particular manufacturer – has proven its use in bringing the product to the attention of new players in the field. The end-of-term evaluation also revealed some weaknesses, such as the need for early involvement of local implementing partners, governments and the private sector, thereby stimulating ownership and ensuring the sustainability of female condom uptake strategies. Also, besides strengthening national health systems, adequate focus should be given towards engaging all market players, aligning priorities, and leveraging each party’s individual expertise to reach the common goal of a healthy sustainable market. The UAFC programme may provide further insights into the potential of such partnerships. The model of engaging with the private sector and coupling the demand and supply of a particular public health commodity may be expanded to other commodities in the field of sexual and reproductive health, and replicated in other countries.

With contributions from: Greetje Lubbi, chair of UAFC steering committee, Marie Christine Siemerink, UAFC coordinator, and Manusika Rai, senior consultant, i+solutions

References

- Global Industry Analysts Inc. (2014). Condoms: A global strategic business report (2014)

- See for more information on FC2®and other brands of female condoms: http://fcmi.org

- Peters A, Jansen W, Van Driel F (2010). The female condom: the international denial of a strong potential. In: Reproductive Health Matters 2010;18(35):119-128

- RHI Shipment Data https://www.myaccessrh.org/rhi-home

- Ibid

- Family Planning Market Report (2015). Clinton Health Access Initiative

- See the female condom market intelligence portal for more information on female condoms, for example the first prototype dating back to 1937, information on R&D, the manufacturers and much more: http://fcmi.org

- In the first phase of the program (2008-2012), UAFC funded 2 functionality studies: a four period randomized non-inferiority cross-over trial designed to evaluate device function, safety, and acceptability of different FCs against the currently marketed control

Beksinska M et al. Performance and safety of the second-generation female condom versus the Woman’s, the VA worn-of-women, and the Cupid female condoms: a randomised controlled non-inferiority crossover trial. Lancet Global Health 2013; Sept 1: e146-52

Beksinska M et al. The Female Condom Learning Curve: Patterns of Female Condom Failure Over 20 Uses. Contraception 2015;91(1):85-90. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.011

Beksinska M et al. A Randomised Non-Inferiority Crossover Controlled Trial of the Functional Performance and safety of New Female Condoms: an evaluation of the Velvet, Cupid2 and FC2. Epub Contraception - Koster W, Groot Bruinderink M (2012). MALE VIEWS ON FEMALE CONDOMS. A Study of Male Acceptance of Female Condoms in Zimbabwe, Cameroon, and Nigeria. Amsterdam: Centre for Global Health and Inequality, University of Amsterdam and Amsterdam Institute for International Development