Main content

In the world’s history, migration has been a prominent feature of humans travelling in search of food, escaping inhospitable climatic conditions, and in response to hardships of war, famine, social injustice and poverty. At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century alone, 60 million people left Europe seeking better lives. Forced migration is still a reality and occurs from and within all continents. As of now, a future in Europe is sought after by unprecedented numbers of refugees from especially Syria and the Horn of Africa, whereas since many decades, Northern America has experienced a continuous influx of people from Mexico and other parts of Latin America but also from Asia. The health problems of these migrants and refugee populations depend to a large extent on the region of origin and the challenges encountered while travelling. On the other hand, immigration to western countries results in migrants moving back and forth, visiting friends and relatives (‘VFRs’), which subsequently leads to import of infectious diseases from the country of origin.

In contrast to migration, which is usually for economic and/or political reasons, tourism is associated with different health risks compared with migrant populations. In the past decades, international travel has shown a marked increase. In 1950 approximately 25 million people from western countries travelled abroad as tourists.

Currently, each year an estimated 50 million travellers from Western countries visit tropical areas of the world, and these numbers are rapidly growing.

Improvements in transportation, changing world economies, increased political stability, the development of tourism as an industry, and increases in travel for business, health related issues and education contribute to this growth.

Trends

Impressive examples from history, such as Stanley’s trans-Africa expedition around 1870 and the French attempt to construct the Panama Canal around the same time, illustrate the heavy toll on Western travellers taken by malaria, sleeping-sickness, yellow fever and other conditions. Even in the 21st century, despite proper preventive measures whether used appropriately or not, Western travellers may contract tropical diseases that, if left untreated, can be fatal within the first few weeks of onset of symptoms. Given the potentially serious consequences for the patients and, in some cases, their close contacts and healthcare workers, it is important that life-threatening tropical diseases are diagnosed quickly.

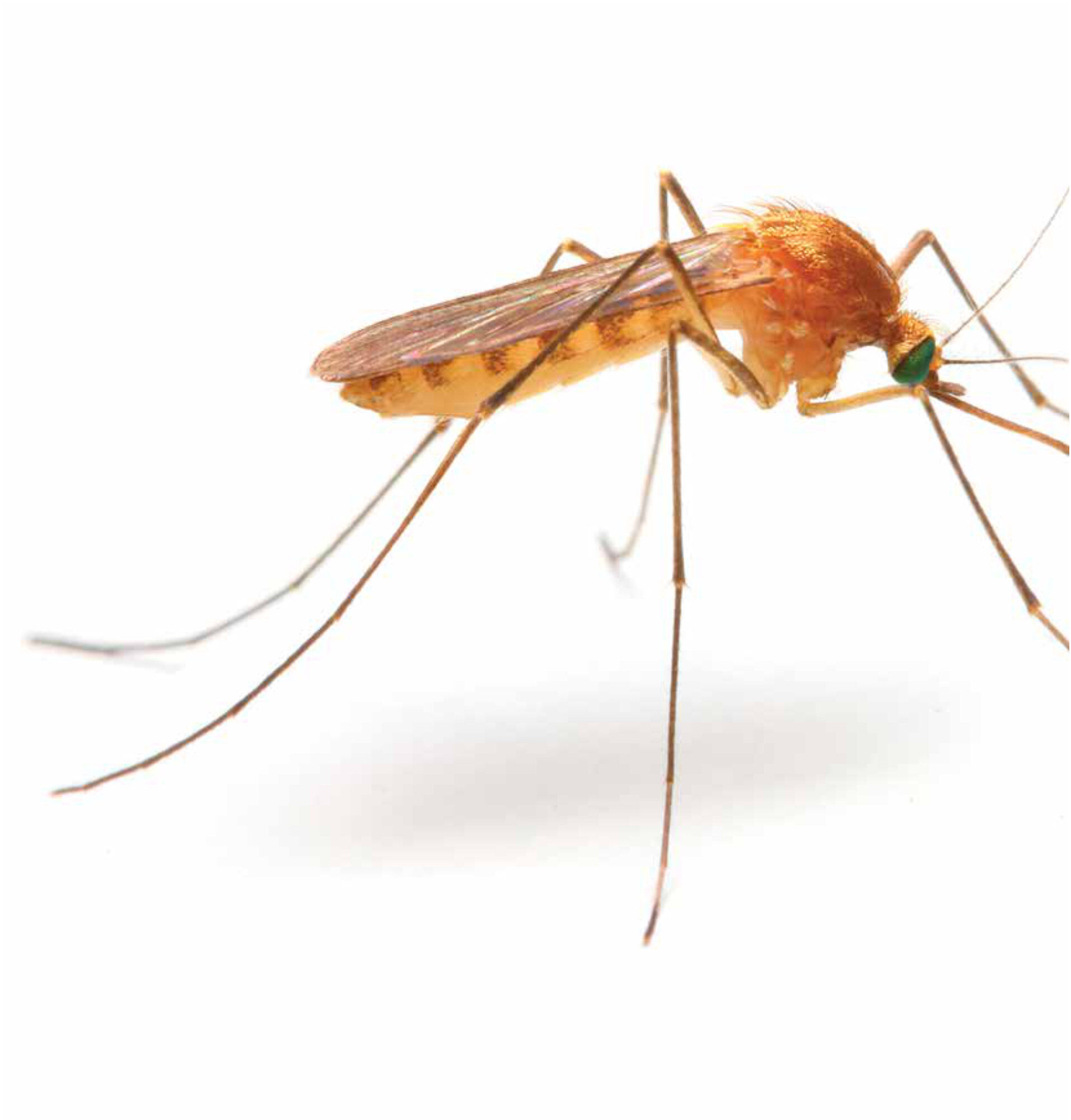

Travel, as well as the extensive worldwide migration flows, plays a major role in the globalization of infections. Dengue, chikungunya and the currently fast spreading epidemic of Zika virus infection in the Caribbean and Central and South America, are prominent examples. Transmission of those three diseases takes place through bites by Aedes mosquitoes, which are present in all tropical and subtropical regions; except for personal protection with repellents and insecticides, no effective preventive measures exist. The emergence of arbovirus infections in southern Europe and the subsequent autochthonous transmission during the summer (when the vector is active) are increasingly being reported. Northern Europeans visiting the Mediterranean basin are at risk, not only because of these new intruders but also due to endemic vector-borne diseases, such as infections caused by viruses spread by sand flies (e.g. Toscana virus infection), leishmaniasis, rickettsial illnesses and emerging threats such as Plasmodium vivax malaria and Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever. The latter disease is still a rarity in most of Europe, but it is endemic in the most south-eastern tip of Europe.

Highly infectious and easily transmitted diseases, for example airborne conditions such as SARS and MERS CoV or viral haemorrhagic fevers such as Lassa fever or Ebola virus disease, pose an enormous local threat and account for many victims in the respective endemic areas. The frequent travel from these areas to non-endemic countries requires immediate countermeasures so as to prevent their introduction in areas that have so far not been affected and to reduce the chance of further man-to-man transmission.

Surveillance

Geosentinel is an organisation that has approximately thirty specialized travel medicine clinics on six continents that contribute to clinician-based sentinel surveillance data on travel-related diseases among travellers who became ill after visiting high-risk countries This initiative has enabled monitoring of trends in the occurrence of travel-related illnesses. EuroTravNet, a daughter network of Geosentinel, generates these data from 18 European sites, facilitating rapid communication of detected disease outbreaks among European travellers.

The 2006 Geosentinel report showed that more than 17,000 travellers returned ill from (sub)tropical countries, with significant regional differences in morbidity in most syndromic categories. Systemic febrile illness without clear focus occurred disproportionately among those returning from sub-Saharan Africa or Southeast Asia, while acute diarrhoea was most prevalent among those returning from south central Asia and dermatological problems among travellers returning from the Caribbean or Central or South America. Overall, malaria was the most frequent cause of systemic illness among ill travellers returning from the tropics, predominantly from sub-Saharan Africa, whereas dengue was the most frequent condition for those who visited the Caribbean, South America and Southeast Asia. Typhoid fever was a primary contributor for systemic febrile illness among travellers returning from south central Asia. Rickettsial infection, primarily tick-borne spotted fever, was seen among travellers from sub-Saharan Africa more often than typhoid fever or dengue. Travellers from all regions except Southeast Asia presented more often with parasite-related induced gastrointestinal complaints (overall most frequently giardiasis) than with bacterial diarrhoea. Insect bites were the most common cause of dermatologic problems, followed by cutaneous larva migrans, allergic reactions, and bacterial skin infections including skin abscesses; again with regional differences. Cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is not uncommon, was found mostly among patients who had travelled to Latin America.

Another study based on Geosentinel data showed that falciparum malaria, mainly from West Africa, was by far the most acute and life-threatening disease in Western travellers, followed by typhoid and paratyphoid fever (south central Asia) and in a minority of cases, but with no less serious a course, leptospirosis and rickettsial diseases.[3]

EuroTravNet travel-associated infection data from the period 2008-2012 show similar results. In its 5-year analysis, increases in vector-borne disease were noticed, particularly falciparum malaria, dengue, and a widening geographic range of acquisition of chikungunya. Acute bacterial and parasitic diarrhoeal illnesses caused high morbidity, similar in magnitude to malaria. Dermatological diagnoses increased over the years, especially of insect bites and animal-related injuries such as dog bites, which may cause the transmission of rabies, while respiratory infection showed an increasing trend, mainly due to the influenza H1N1 pandemic of 2009. Migration was associated with infection of hepatitis B and C, and tuberculosis. Chronic Chagas disease which may be imported by migrants from South America to Europe (mainly Spain) and to North America may be underestimated as it has not only serious consequences for the patients themselves but also for any blood products donated by them, which calls for appropriate screening.[5]

What more can we expect?

The above reports and the database are an important tool in travel medicine and are instrumental in designing measures in case of outbreaks, but they do not represent a comprehensive epidemiologic analysis of all illnesses in all travellers. Neither do they provide a representative sample of illnesses in returned travellers, such as those seen at non-specialized primary care centres, where they usually present with mild or self-limited conditions. Diseases with short incubation periods or diseases that seemed not so serious when the person was still travelling are another cause of under-reporting.

Communicable diseases, which often present themselves unexpectedly, will continue to emerge and re-emerge.[6] New infections will emerge, changing patterns in host immunity will occur, and changes in climate and migration will influence their epidemiology. This requires continuous and accurate surveillance so as to reduce the unnecessary burden of morbidity and mortality. Appropriate pre-travel advice and intervention strategies based on the continuum of these surveillance data will help to reduce this burden.

Declaration of conflict of interest

Both authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2014, World Tourism Organization, Madrid (2014) http://dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_highlights14_en.pdf.

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk T, Robins R, von Sonnenburg F, Keystone JS, Pandey P, Cetron MS; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:119-30.

- Jensenius M, Han PV, Schlagenhauf P, Schwartz E, Parola P, Castelli F, von Sonnenburg F, Loutan L, Leder K, Freedman DO; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Acute and potentially life-threatening tropical diseases in western travelers–a GeoSentinel multicenter study, 1996-2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;88:397-404.

- Schlagenhauf P, Weld L, Goorhuis A, Gautret P, Weber R, von Sonnenburg F, Lopez-Vélez R, Jensenius M, Cramer JP, Field VK, Odolini S, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Chappuis F, Malvy D, van Genderen PJ, Mockenhaupt F, Jauréguiberry S, Smith C, Beeching NJ, Ursing J, Rapp C, Parola P, Grobusch MP; EuroTravNet. Travel-associated infection presenting in Europe (2008-12): an analysis of EuroTravNet longitudinal, surveillance data, and evaluation of the effect of the pre-travel consultation. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:55-64.

- Gautret P, Cramer JP, Field V, Caumes E, Jensenius M, Gkrania-Klotsas E, de Vries PJ, Grobusch MP, Lopez-Velez R, Castelli F, Schlagenhauf P, Hervius Askling H, von Sonnenburg F, Lalloo DG, Loutan L, Rapp C, Basto F, Santos O’Connor F, Weld L, Parola P; EuroTravNet Network. Infectious diseases among travellers and migrants in Europe, EuroTravNet 2010. Euro Surveill. 2012 Jun 28;17(26).

- Goorhuis A, von Eije KJ, Douma RA, Rijnberg N, van Vugt M, Stijnis C, Grobusch MP. Zika virus and the risk of imported infection in returned travelers: implications for clinical care. Travel Med Infect Dis 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.01.008.