Main content

For about forty years, the first author (JvH) has been involved in the training and education of various mental health professionals in the Netherlands, South Africa, Gambia, Russia, China, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. Through the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO Cambodia), he became affiliated with the Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital (KSFH) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, since 2015. HealthNet TPO is a global aid agency with roots and its headquarters in the Netherlands, which has been working on restoring and strengthening health care systems in areas disrupted by war or disaster since 1992. The organisation is the result of a merger (in 2005) of the former TPO International and HealthNet. TPO Cambodia was established in 1995 as a branch of the former TPO International and registered in Cambodia as a not-for-profit NGO in 2010.

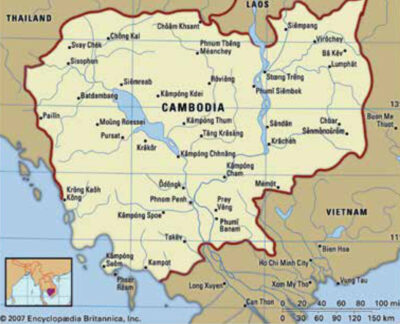

Cambodia and its history

Nowadays Cambodia is one of the poorest countries in South-East Asia. However, it is a country with a glorious history between the 9th and the 14th century when the Khmer Empire covered a large part of the region, including Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Malaysia. Thereafter, the country experienced turbulent periods of occupation, civil war, and the devastating regime of the Khmer Rouge led by Pol Pot. During this regime (1975-1979), over two million people were killed or died due to starvation and disease. The subsequent years brought misery until the Paris Peace Agreements of 1991, which ended the Cambodian-Vietnamese war.

Mental health care workforce after the Paris Peace Agreements (1991)

At that time, the public health system of Cambodia was demolished, and only a few medical doctors and other health workers were still active. Quoting Daniel Savin: ‘In 1979, none of 43 surviving medical doctors in Cambodia were psychiatrists.[1] Many higher educated people were killed in the name of the revolution of the Pol Pot regime.

Immediately after the peace agreements, the Cambodian government formed international partnerships with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the University of Oslo in cooperation with Harvard University for the training of 26 psychiatrists and 40-45 psychiatric nurses. However, since the original training programmes ended, there has been no regular training of psychiatric nurses.[2] Regarding medical specialists, the Cambodian University of Health Sciences took over the three-year psychiatry residency training programme.

Present status of mental health care

Currently, Cambodia has about 16 million inhabitants. The present status of mental health care in Cambodia is reflected in the total number of mental health specialists. Cambodia has about sixty psychiatrists,[3] which is fifty times less (calculated per 100,000 inhabitants) than the Netherlands.

In addition, there are currently about 200 psychologists working in Cambodia as compared to 16,000 in the Netherlands.[4] There are also only a few government mental health clinics operating, predominantly located in urban centres. Finally, the total number of psychiatric in-patient beds is below twenty. Since 2010, there have been strategic plans to improve mental health care in the country, particularly to increase the number of specialised clinics and enhance resources. However, in 2016, it was clear that the system was still ill-equipped and provided only limited services. Funding remained too low, resources too limited, and training initiatives and projects frequently relied on external funding.[5,6] Information on the training of psychiatrists and psychologists is presented in Table 1.

TPO Cambodia and our visits

TPO International engaged in the promotion of mental health in war and conflict zones worldwide, and started a community based mental health programme in Cambodia in 1995, with the aim of identification, prevention and management of psychosocial problems. In the beginning, a core group was formed by Willem van de Put and Maurice Eisenbruch,[7] which consisted of Cambodians who were offered culturally appropriate and relevant training, monitoring and supervision – based on the daily experience of assessing existing problems and identifying realistic solutions in the field of psychosocial problems in the community. For example, in rural villages patients with psychotic disorders were of most concern and therefore the staff of local hospitals were trained in basic mental health care to cope with these patients. Since 2000, the project has continued its activities as the independent TPO Cambodia.[8] Nowadays, TPO Cambodia is a relatively large Cambodian NGO, which plays a trendsetting and educational role in mental health care developments. They realise outpatient and social psychiatric care, particularly in rural areas, and broadly provide information in the field of mental health.

The first author (JvH) has participated in TPO Cambodia’s capacity building programme since 2015, both in the capital Phnom Penh as well as in rural areas. The capacity building programme consists of lecturing, training small groups of psychiatrists, residents, psychologists and students on main psychiatric diseases, diagnostic procedures through roleplaying, and communication with patients.

The multi-disciplinary programme operation and evaluation provided the following insights concerning mental health care practice. Patient problems in various areas of life are evaluated and treated individually, without considering the mutual relationships between psychosocial and medical problems. In other words, it is not common practice to link the dynamics of the psychosocial system and the dynamics of the interpersonal communication with the stress put on the patient and the mental decompensation. Therefore, a broader understanding should be developed of the pathogenesis of the psychiatric disorder in a specific patient. We also missed the contribution of patient organisations in the psychoeducation and sharing of common problems of patients. There seems to be little coherence in visions and working models of psychosocial workers, psychologists and psychiatrists. This appeared especially relevant in the treatment of therapy-resistant patients. Therefore, in the programme, we performed a multilevel problem analysis, with a biopsychosocial model for better understanding the problems that the patients and their families are confronted with. On the basis of this analysis, therapeutic interventions were proposed. In addition to system interventions, psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatments of these patients were discussed. In Phnom Penh, many thousands of people are treated with antidepressants, but many of them are treatment resistant and require other therapy. For these patients, we introduced electroconvulsive therapy as a potential treatment, discussed its indication assessment, and also performed training on its application.

Finally, in the rural areas we provided training to various TPO Cambodia teams of mental health workers and employees of local hospitals, in particular on how to conduct a psychiatric interview and topics like depression, schizophrenia, and addiction. Through our conversations, we obtained insight into the great constraints of mental health care in these areas.

Experience-driven recommendations to adapt mental health in Cambodia

Based on the experiences of the first two authors (JvH, SR) with co-workers and also the conversations with leading people in the government, hospitals and NGO’s, we made the following recommendations for improvement in mental health care in Cambodia, which we will incorporate in the development of our future programmes.

- Promote multidisciplinary cooperation, e.g. in the KSFH also psychologists and social workers could do a lot of good work, while they are absent now. Furthermore, experts from ministries, hospital managements, and assurance companies, practitioners, and traditional healers could focus more on joint attention and cooperation.

- Psychotherapy could be used also in a much more integrated manner. In this respect, it would be advisable to integrate the education of psychologists and psychiatrists in order to improve cooperation.

- Psychiatry could benefit from more frequent use of second generation psychotropics, like lithium and clozapine, especially for treatment of therapy-resistant patients. However, in that case, laboratory facilities have to be improved to enable measurement of lithium plasma levels, measurement of thrombocytes and further blood picture, and measurement of drug plasma levels.

- Patient organisations could be initiated or strengthened, e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous could be invited to settle in the cities as well as in rural areas.

- The highly motivated new generation of psychiatrists and psychologists should be facilitated in further extending their knowledge, e.g. by attendance of conferences or summer schools (also abroad).

- Under the guidance of governmental institutions and local NGOs, consultation and education by mental health care professionals from abroad could make a difference. The recent initiative of the department of transcultural psychiatry of the Netherlands Psychiatry Association to establish a group of psychiatrists interested in global mental health could also support projects in Cambodia with required expertise and means.

These recommendations were positively received by TPO Cambodia and the colleagues at KSFH. In addition to internal Cambodian considerations, these ideas convinced AROM, the recently initiated platform of psychiatrists and psychologists, to prioritise the cooperation between both disciplines.

Acknowledgements

We thank the employees of the Louvain Cooperation Cambodia, especially Amaury Peters and Khem Thann, of ΤΡΟ Cambodia, of The RUPP and KSFH, who supported JvH’s visit to Cambodia and were prepared to share their thinking with him. JvH also thanks all residents and students who made his teaching sessions an enriching experience.

Cambodia has about sixty psychiatrists, which is fifty times less (calculated per 100,000 inhabitants) than the Netherlands there are about 200 psychologists working in Cambodia as compared to 16,000 in the Netherlands

References

- Savin D. Developing psychiatric training and services in Cambodia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000 Jul;51(7):935. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.935

- Olofsson S, San Sebastian M, Jegannathan B. Mental health in primary health care in a rural district of Cambodia: a situational analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018 Jan 24;12:7. DOI: 10.1186/S13033-018-0185-3

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Mental Health ATLAS 2017 Member State Profile. 2017 [cited 2020 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles-2017/KHM.pdf?ua=1.

- Capaciteitsorgaan. Capaciteitsplan 2020-2024: Beroepen Geestelijke Gezondheid: Deelrapport 7 [Internet]. Utrecht, 2018 [cited Nov 2 2020] 109 p. Available from: https://capaciteitsorgaan.nl/app/uploads/2018/11/2018-11_02-DE Capaciteitsplan-BGGG-2020-2024.pdf

- Parry SJ, Wilkinson E. Mental health services in Cambodia: an overview. BJPsych Int. 2020 May;17(2):29-31. DOI: 10.1192/bji.2019.24

- Jegannathan B, Kullgren G, Deva P. Mental health services in Cambodia, challenges and opportunities in a post-conflict setting. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015 Feb;13:75-80. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.12.006

- Somasundaram DJ, Van de Put WA, Eisenbruch M, et al. Starting mental health services in Cambodia. Soc Sci Med. 1999 Apr;48:1029-46. DOI: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00415-8

- TPO Cambodia [Internet]. About us; [cited 2020 Nov 2]. Available from: https://tpocambodia.org/tpo-about/