Main content

Most medical professionals will correctly answer the question ‘Is HIV the cause of AIDS?’ by stating that an infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) will cause Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) by impairing the human immune system. However, the answer to this question and thereby the prevention of an HIV infection is more complex than this.

Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS

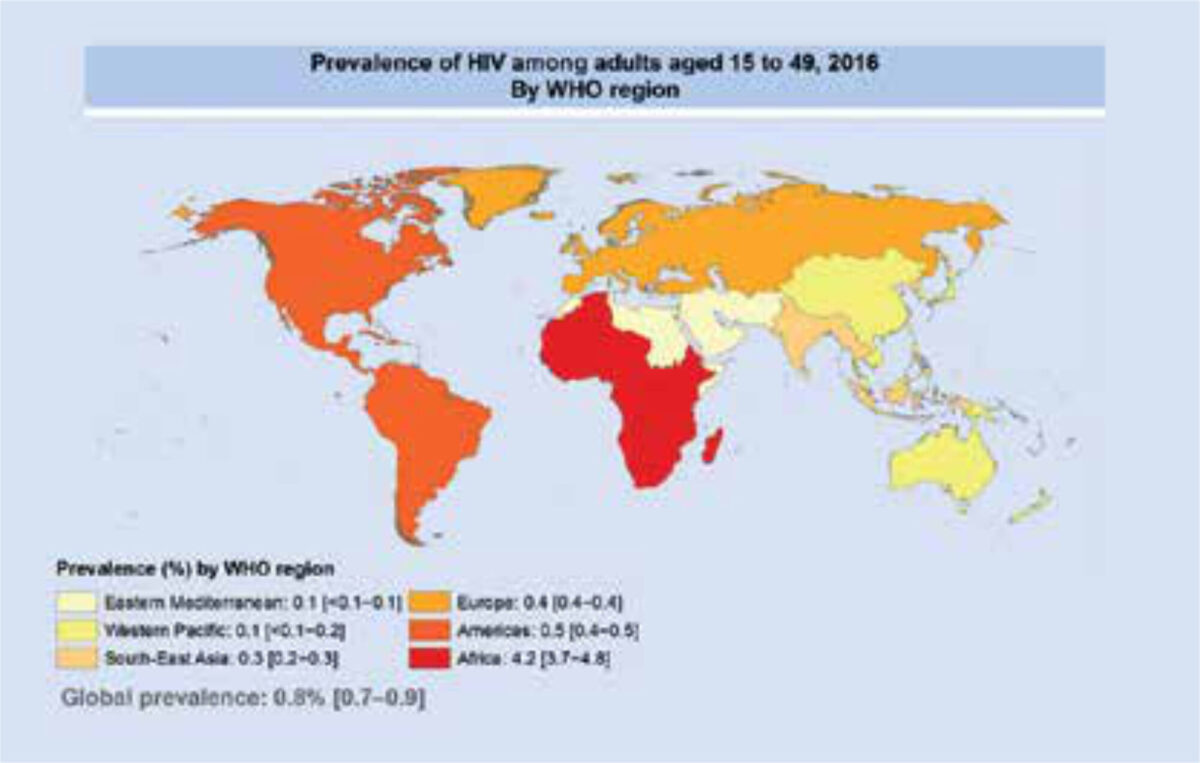

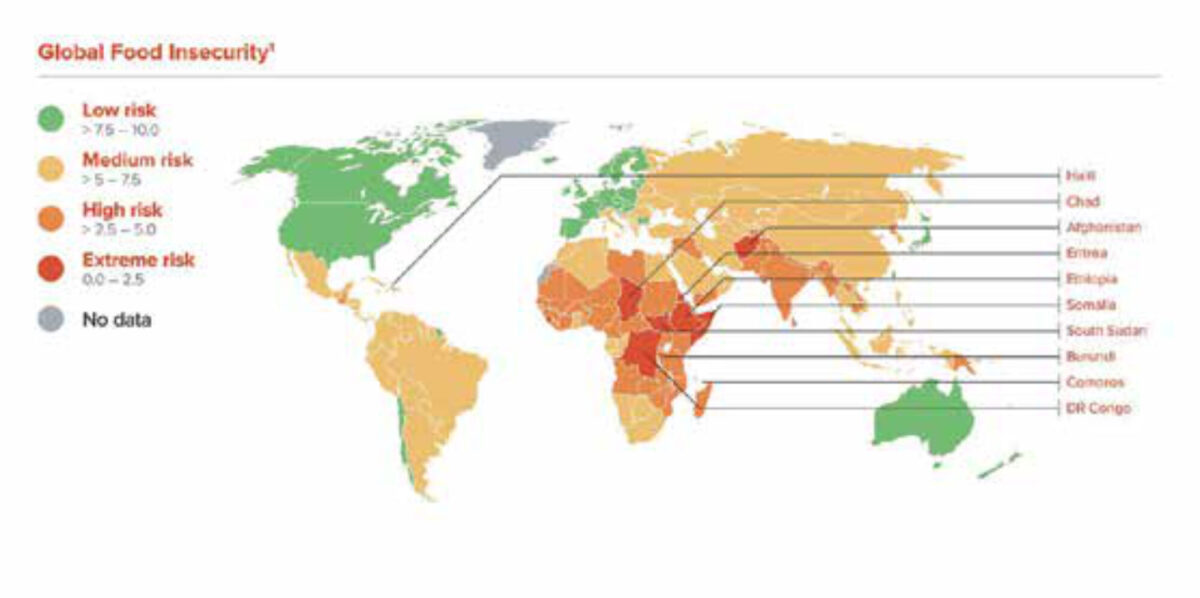

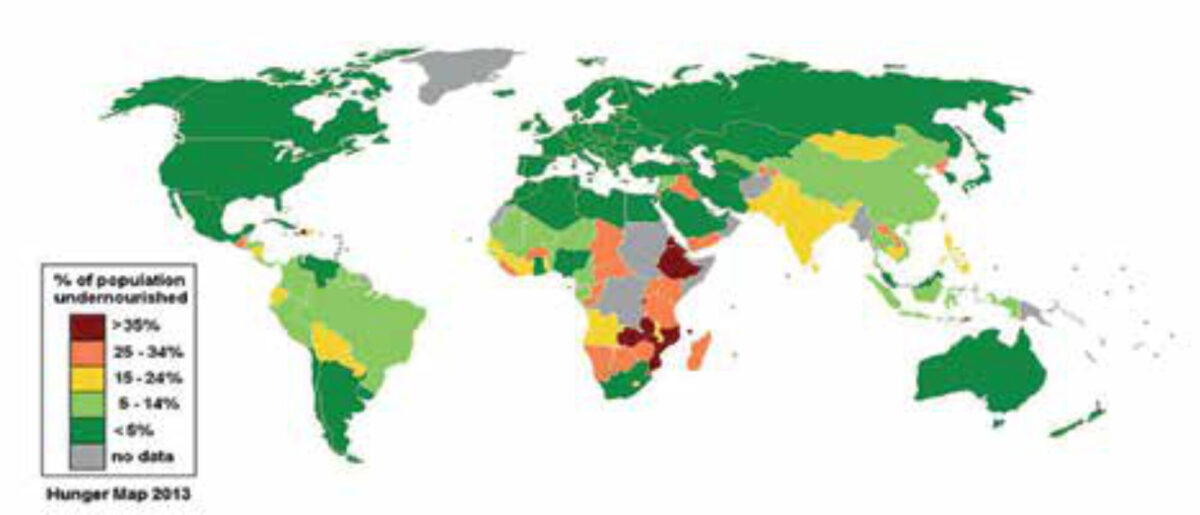

In 2016, 1.8 million people became newly infected with HIV, adding to the current total of 36.7 million people living with HIV.[1] Since the identification of HIV in 1981, 35 million lives have been lost to HIV/AIDS. One million people died from HIV-related causes globally in 2016.[2] The global scale-up of antiretroviral therapy, including higher treatment coverage and increased adherence to this treatment, has been instrumental in a 48% decline in deaths from AIDS-related causes in the last decade. This therapy plays an important role in controlling the virus, slowing down the progression of AIDS and preventing HIV transmission, thereby ensuring that people living with HIV as well as those at risk can enjoy healthy and productive lives.[2,3] Although there is currently no cure for HIV, one of the Sustainable Development Goals is to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. The UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets form an important part of this goal: 90% of HIV infected people will be diagnosed, 90% of the diagnosed people will receive antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of the people receiving treatment will be virally suppressed, all by 2020.[4] Currently an estimated 70% of people infected with HIV are aware of their status and 77% of these receive treatment. This translates into 54% of adults living with HIV worldwide having access to lifelong highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).[2] Of the people receiving treatment, 82% are virally suppressed.[1] Although this is a remarkable achievement, there is still much more to do. In order to maintain a healthy and good quality life and to improve survival for individuals infected with HIV, nutrition and food security play an important role. The bi-directional relationships and interactions between HIV/AIDS, nutrition and food security are complex.[5] As is shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3, the HIV epidemic largely overlaps with populations who are malnourished and do not have or are at risk of not having access to sufficient quantities of good-quality food.

Maps showing overlap in prevalence of HIV, food insecurity and undernutrition.

Source: United Nations World Food Programme.[15]

Nutrition and HIV/AIDS

Nutritional status affects the maintenance and optimal functioning of the immune system and therefore the health status and progression of HIV/AIDS. Early in the HIV epidemic, slim disease, as a result of protein-calorie malnutrition (wasting) with depletion of lean mass, fat, and micronutrients, was a condition associated with chronic diarrhoea and/or prolonged fever. Malnutrition and hunger increase vulnerability to HIV by weakening the body and the immune system and may lead to shortened survival and diminished quality of life. For those who have already been infected with HIV, malnutrition enhances the risk of opportunistic infections and a further and faster progression of AIDS. An HIV infection may cause decreased food intake (caused by pain during eating and vomiting for example), nutrient malabsorption, metabolic alterations, and increased energy and protein requirements. This leads to several complications, among which wasting has been established as a strong predictor of mortality in HIV-infected people, as already recognized early in the epidemic.[6] In addition, malnutrition can reduce the effectiveness and acceptance of HAART and other therapies.[7] Good nutritional status can strengthen the immune system and increase resistance to (opportunistic) infections related to HIV/AIDS, whereas malnutrition has the opposite effect.[8]

Food security and HIV/AIDS

Poverty-induced malnutrition and HIV are related to food insecurity, as it is more difficult to obtain nutritious food that keeps HIV infected people healthy for longer periods in resource-poor settings. Food security is an important concept that extends beyond the individual and relates not only to good-quality food intake but also links it to health, (sustainable) economic development, environment and trade.[9] In relation to the different aspects contributing to the concept of food security, different definitions for food security exist. The one most used is a refined version of the one developed at the World Food Summit in 1996: ‘Food security [is] a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’.[10] In 2016, 687 million people were affected by severe food insecurity, and an estimated 815 million people were undernourished globally.[9] HIV infection reinforces pre-existing food insecurity while food insecurity may increase vulnerability to HIV. Hunger and poverty are determinants of risky ‘survival activities’, such as prostitution, migration and dropping out of school at an early age, increasing the risk of acquiring HIV.[11] Most HIV infections occur in people between the ages of 20 years and 29 years, also the peak childbearing years. This has a systemic impact on the social and economic systems in countries affected by AIDS, and these effects extend to children and their wider families. In addition, people infected with HIV and their families also face stigma and discrimination. Being infected with HIV can result in not being able to work leading to a decrease in food production or income for the household. In addition, the costs of health care utilisation, lost income due to care for people infected with HIV, funeral costs, and the care for orphans lead to more poverty and hunger and eventually to more food insecurity.[9,12]

Understanding the context of the cause of a disease can be the difference between life and death, especially in the case of AIDS. HIV does not necessarily lead to AIDS if the infected person is well-nourished and in a good physical condition. Hence, addressing malnutrition and food insecurity is crucial in mitigating the impact of HIV and the households and communities affected [5] and must be tailored to specific settings.[1] One individual HIV infection, especially in combination with malnutrition and food insecurity, causes a ripple effect with enormous consequences for that particular person, the household, the wider community and the country as a whole.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data 2017. Report. 2017. Geneva, Switserland. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf Accessed on: 26 April 2017.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fact sheet HIV/AIDS. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids Accessed on: 26 April 2017.

- May MT, Ingle SM. ‘Life expectancy of HIV-positive adults: a review’. Sexual Health. 2011;8(4): 526-33.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90-90-90. An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Report. 2014. Geneva, Switserland. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf Accessed on: 26 April 2017.

- The World Bank. HIV/AIDS, nutrition, and food security: What can we do? An synthesis of international guidance. Report. 2007. Washington DC, United States of America. Available online: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/NUTRITION/Resources/281846-1100008431337/HIVAIDSNutritionFoodSecuritylowres.pdf Accessed on: 26 April 2017.

- Mankal PK, Kotler DP. From wasting to obesity, changes in nutritional concerns in HIV/AIDS. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2014; 43(3):647-63.

- Chandrasekhar A, Gupta A. Nutrition and disease progression pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and post-HAART: can good nutrition delay time to HAART and affect response to HAART? Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94(6):1703S-1715S.

- De Pee S, Pemba RD. Role of nutrition in HIV infection: Review of evidence for more effective programming in resource-limited settings. Food Nutr Bull 2010; 31(4):S313-S344.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017. Building resilience for peace and food security. Report. 2017. Rome, FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-17695e.pdf Accessed on: 26 April 2017.

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2001. Report. 2002. Rome. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/y1500e/y1500eoo.htm Accessed on: 26 April 2017.

- Frega R, Duffy F, Rawat R, Grede N. Food insecurity in the context of HIV/AIDS: A framework for a new era of programming. Food Nutr Bull 2010; 31(4):S292-S312.

- Parker DC, Jacobsen KH, Komwa MK. A Qualitative Study of the Impact of HIV/AIDS on Agricultural Households in Southeastern Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(8):2113-2138.

- World Health Organisation. HIV/AIDS Global situation and trends. Global Health Observatory data. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/ Accessed on 27 April 2018.

- Maplecroft. Food security risk index. Risk calculators and dashboards. Available online: https://maplecroft.com/about/news/food_security_risk_index_2013.html Accessed on 27 April 2018.

- Annan R. My Rio2012 vision. Column on website of the World Public Health Nutrition Association, 2012. Available online: http://www.wphna.org/htdocs/2012_may_col_reggie.htm Accessed on 27 April 2018.