Main content

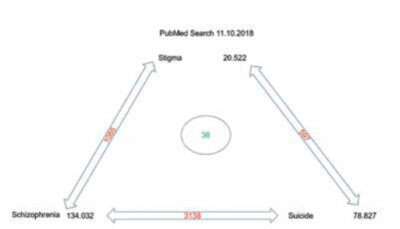

In old Greek, the word στίγμα (stigma) had the meaning of ‘brand, to be branded, to be marked’. Over the ages up till our time it has evolved into a mark of disgrace, associated with a particular circumstance, quality or person. Stigma plays an important role in mental health, as it influences the way psychiatric patients are perceived by the general population and how patients see themselves.[1] It is interesting to see how stigma relates to or interacts with schizophrenia, and suicide. For this reason a PubMed search was conducted in 2018 with the terms ‘stigma’, ‘schizophrenia’ and ‘suicide’. This resulted in large numbers of published articles: stigma 20,522, schizophrenia 134,032 and suicide 78,827. I will discuss the interaction between these three conditions.*

Stigma and health**

Extensive research has been done on stigma in relation with leprosy and with HIV/Aids, both communicable diseases. Nsaga et al. (2011) found that the more people were affected within the community, the smaller the stigma, present and perceived.[2] This probably means that the ‘social stigma’ was small. Social or external stigma is different from internal stigma, which eats away at people’s self-esteem and self-efficacy. The Jewish woman wearing a yellow star (Figure 1) will initially have suffered from social stigma, but later on this might have evolved into internal stigma, had she been given the time to live.[3,4] Prisoners in orange overalls are stigmatised by those orange overalls, social stigmata, which, depending on the duration of their imprisonment might or might not evolve into self-stigma. Then again, within the prison walls, as in a ghetto, stigma will be less. Research in the field of HIV/AIDS has shown that, because of the already existing social stigma, internal stigma plays an important role resulting in persons hiding the fact that they are infected. Mhode et al. describe another form of stigma: ‘anticipated stigma’.[5] In Dar es Salaam, they found that, in order to avoid stigma, persons infected with HIV became secretive and, rather than seeking medical advice, devoted themselves to spirituality. However, if they were able to accept the reality of the situation, they could become proud bearers of the term ‘living with HIV’, supporting themselves and others in self-help groups[6] – thus, reducing internal stigma and, by opening up to the community as a whole, hopefully reducing social stigma.

Stigma and suicide

Both social and internal stigma have been associated with suicide and suicide attempts. Every year approximately 100,000 people in the Netherlands attempt to end their lives; in 2019 suicide attempts totalled 1,811. To help people considering suicide and to avert the fatal outcome, a programme was started in 2009 by the late Jan Mokkenstorm. In April and May 2013 alone, 1,732 people contacted 113 Zelfmoordpreventie (Suicide prevention), an emergency telephone number and online service that was initiated just one year after the programme had started. It turned out that 46% of those seeking contact were receiving psychological treatment, and when the content of the chats was analysed, 41% had objectifiable psychiatric symptoms.[7] Surprisingly, more than half the people with suicidal ideations were not receiving psychological treatment, and their suicidal thoughts were not in themselves linked to a manifest psychiatric disorder. It can be assumed that 113 Zelfmoordpreventie has also worked in several ways to reduce stigma. First, due to the anonymity guaranteed to users, the role of internal stigma was reduced. Secondly, spearheading a campaign to bring the problem of suicide into the open also reduced social stigma.

In my initial search, 597 publications addressed both stigma and suicide. Carpiniello and Pina came to the following conclusions: ‘self-stigma’ develops in a person having committed one or several suicide attempts and in the relatives of this person; ‘social stigma’ exists in the community towards suicidal persons and in the community towards relatives of those having committed suicide.[8] Their findings are supported by Moore et al., who found that ‘inmates face many hardships once they are released into the community and are being stigmatized. Being an ex-offender is often found to be a major barrier to successful community reintegration.'[9]

Stigma and schizophrenia

In my search, 1,065 publications addressed both stigma and schizophrenia. Two of those publications are especially interesting for our purpose. Assefa et al., from Addis Ababa, use ‘experienced stigma’ and ‘internalized stigma’ as their parameters.[10] These are comparable to social and internal stigma respectively. In a group of 212 patients, using the diagnosis of schizophrenia via an Amharic version of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale, they found a 50% to 72% range of internalized stigma. They also found that the level of internalized stigma in patients with schizophrenia was comparable to internal stigma in European patients with schizophrenia.[11] Factors associated with a higher level of internalized stigma were: rural residence, single marital status, and prominent psychotic symptoms.

In Istanbul, Ücok et al. interviewed 103 stable outpatients with schizophrenia and found that a low level of symptoms correlated with a lower degree of anticipated stigma at school or work.[12] If more pronounced symptoms were present, the opposite was true.

Schizophrenia and suicide

Of the 2014 publications addressing schizophrenia and suicide in my search, I will discuss just one. Cassidy et al. (2018) published a meta-analysis on risk factors for suicidality in patients with schizophrenia. They conclude that ‘suicidal ideation’ is related with high scores on BDI and HAM-D, a high score on PANSS, and a greater number of psychiatric hospitalizations; ‘suicide attempt’ is associated with hopelessness, history of depression, history of attempted suicide, family history of psychiatric illness, family history of suicide, being white, and history of addiction; ‘suicide’ is more frequent with shorter illness length, younger age, and higher IQ.[13]

Stigma, schizophrenia, and suicide***

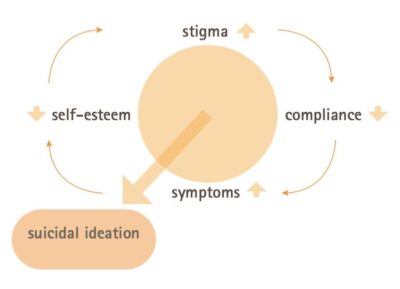

Of all the articles sampled in my search, only 38 addressed stigma and schizophrenia and suicide. From the six publications listed in Table 1 and their main conclusions, one may conclude that, worldwide and across cultures, the interaction between stigma, schizophrenia and suicide is important and significant (Figure 2 and 3).

A paper by Shrivashtava et al. on a study in Toronto sums up the dilemmas health workers face when working with people suffering from schizophrenia.[14] They found that stigma delays treatment seeking, worsens course of burden and outcome, reduces compliance, and increases the risk of relapse.

Discussion

Psychiatrists in their daily work often find that patients with schizophrenia, experiencing stigma and considering suicide, find themselves in a vicious circle. The question arises: where and how can we stop going in circles and reduce dramatic outcomes? We can treat psychosis and we can reduce suicide by addressing the topic candidly with our patients. Stigma however is not always considered during patient consultations. Recognising and discussing stigma can interrupt the vicious circle. This would be in line with the advice of Shrivastava et al, who state that stigma needs to be assessed during routine clinical examination, and subjected to further research in order to develop measurable objective criteria and assess whether treatment can reduce the effects of stigma on patients.[14]

| Collett N, Pugh K, et al. | United Kingdom | 2015 |

| Marked negative self-cognitions and high levels of suicidal ideations in patients with persecutory delusions | ||

| Stip E, Caron J, et al. | Canada | 2017 |

| Perceived cognitive dysfunction and stigmatisation contribute to the onset of suicidal ideation | ||

| Yoo, Kim, et al. | South Korea | 2015 |

| Low self-esteem closely related to suicidal ideation | ||

| Lien YJ, Chang HA, et al. | Taiwan | 2017 |

| Positive correlation between low self-esteem, insight and suicidal attempts | ||

| Touriño R, Acosta FJ, et al. | Spain | 2018 |

| Association between internalised stigma, higher hopelessness, depression and higher suicidality | ||

| Sharaf AI, Ossman LH, et al. | Egypt | 2012 |

| Internalised stigma and depression independently predicted suicide risk | ||

Conclusion

In the interest of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and their relatives, stigma and suicidal thoughts need to be discussed as part of treatment and care. One might ask, ‘Where do we go from here; how can we reduce stigma?’ A recent systematic review by Clay et al. gives an overview of methods shown to be effective in low- and middle-income countries, including: health education and myth busting by using informal groups, broadcasting, and social media.[15]

Author’s remarks

* In the literature different forms of stigma are mentioned: social, external, internal, and anticipated stigma, to name just a few. For our purpose the dichotomy between social and internal suffices

** Social stigma is the societal disapproval (or discontent) that a person or group perceives based on particular characteristics, and which some people use to distinguish them from other members of a society. Stigma may then be affixed to such persons, by society at large, as they seem to differ from the mainstream cultural norms

*** BDI and HAM-D are scales to rate depression; PANSS rates psychotic symptoms

References

- Mutiso VN, Musyimi CW, Tomita A, et al. Epidemiological patterns of mental disorders and stigma in a community household survey in urban slum and rural settings in Kenya. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018 Mar;64(2):120-29. DOI: 10.1177/0020764017748180

- Nsagha DS, Bamgboye EA, Nguedia Assob JC, et al. Elimination of leprosy as a public health problem by 2000 AD: an epidemiological perspective. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;9:4. DOI: 10.4314/pamj.v9i1.71176

- Ultee W, Van Tubergen F, Luijkx R. The unwholesome theme of suicide. Forgotten statistics of attempted suicides in Amsterdam and jewish suicides in the Netherlands for 1936-1943. In: Brasz C, Kaplan Y, editors. Dutch jews as perceived by themselves and others. Leiden: Brill; 2001. p. 325-35

- Levav I, Brunstein Klomek A. A review of epidemiologic studies on suicide before, during, and after the Holocaust. Psychiatry Res. 2018 Mar;261:35-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.04

- Mhode M, Nyamhanga T. Experiences and impact of stigma and discrimination among people on antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam: a qualitative perspective. AIDS Res and Treat. 2016;2016:7925052. DOI: 10.1155/2016/7925052

- Casale M, Boyes M, Pantelic M, et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviour among South African adolescents living with HIV: can social support buffer the impact of stigma? J Affect Disord. 2019 Feb 15;245:82-90. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.102

- Mokkenstorm JK First two year results at ESSSB14 Tel Aviv sept 2012 [presentation]. 2012. Available from: https://www.slideshare.net/mokkenstorm/113-online-suicide-prevention

- Carpiniello B, Pinna F. The reciprocal relationship between suicidality and stigma. Front Psychiatry. 2017 Mar 8;8:35. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00035

- Moore K, Stuewig J, Tangney J. Jail inmates’ perceived and anticipated stigma: implications for post-release functioning. Self Identity. 2013 Jan 1;12(5):527-47. DOI: 10.1080/15298868.2012.702425

- Assefa D, Shibre T, Asher L, et al. Internalized stigma among pati patients with schizophrenia in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional facility-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Dec 29;12:239. DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-239

- Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, et al. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res. 2010 Sep;122(1-3):232-38. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1065

- Üçok A, Karadayı G, Emiroglu B, et al. Anticipated discrimination is related to symptom severity, functionality and quality of life in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013 Oct 30;209 (3):333-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.022

- Cassidy R, Yang F, Kapczinski F, et al. Risk factors for suicidality in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 96 studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018 Jun 6;44(4):787-97. DOI: 10.1093/schbul/sbx131

- Shrivastava A, Bureau Y, Rewari N, et al. Clinical risk of stigma and discrimination of mental illnesses: need for objective assessment and quantification. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;55(2):178-82. DOI: 10.4103/0019.5545.111459

- Clay J, Eaton J, Gronholm PC, et al. Core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020 Sep 4;29:2164. DOI: 10.1017/S2045796020000797