Main content

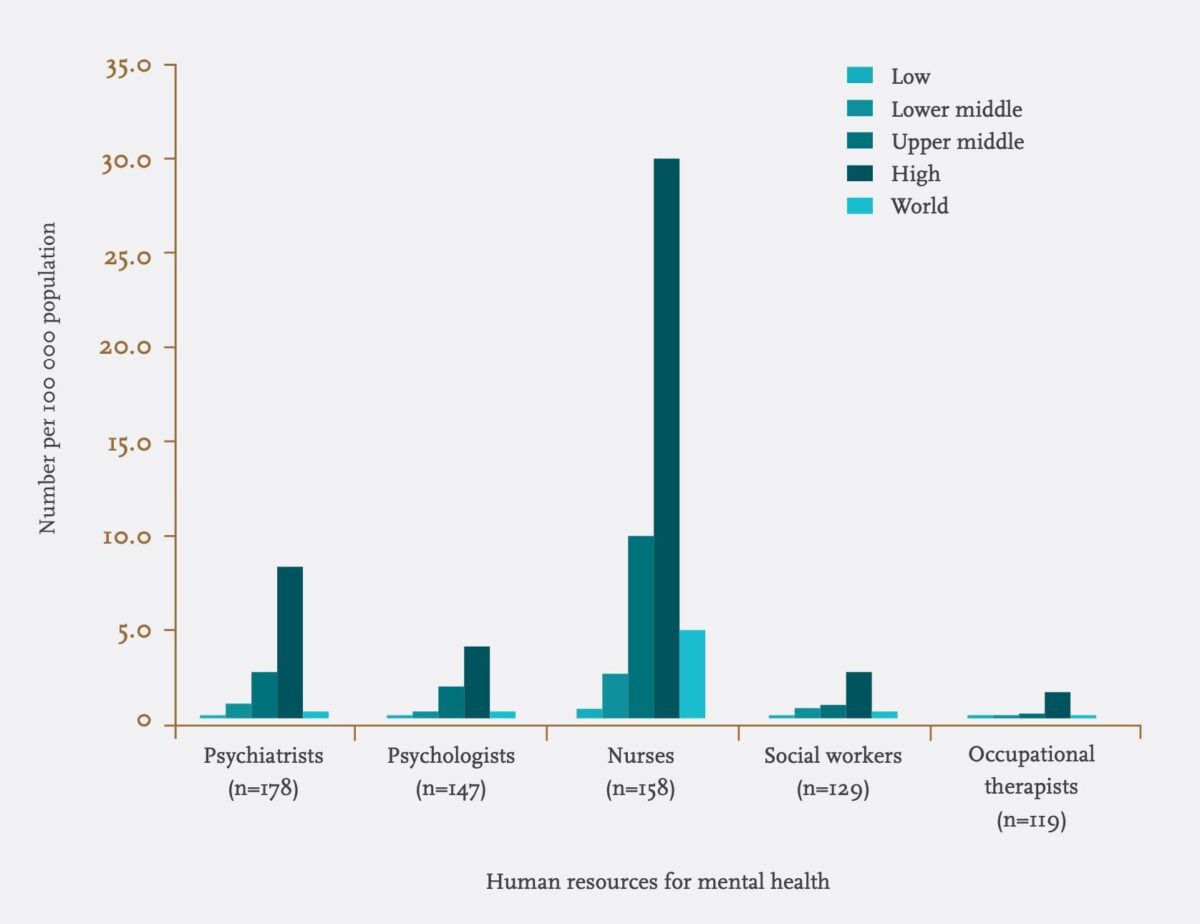

The website of the World Health Organization (WHO) on the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) opens by stating that “mental, neurological, and substance use disorders are common in all regions of the world, affecting every community and age group across all income countries. While 14% of the global burden of disease is attributed to these disorders, most of the people affected – 75% in many low-income countries – do not have access to the treatment they need”. The term ‘gap’ refers to this lack of available services. The relative lack of mental health professionals in low- and lower-middle-income countries, as shown in figure 1, may serve as an illustration.

Income groups defined by the World Bank, 2010.

The populations of low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) would need an extra 239,000 full-time mental health staff for just eight mental, neurological and substance abuse related problems in order to close the treatment gap. It is not to be expected that this kind of capacity building will be achieved over the coming few decades. Meanwhile, tens of millions may not receive proper care, psychosocial assistance and medication. Notably, the WHO states that the reality is that most conditions in this field of expertise can be managed by non-specialist health care providers. What is required is increasing the capacity of the primary health care system for delivery of an integrated package of care by training, support and supervision.³

The latter is the very objective of mhGAP, an action programme that was launched by WHO in 2008. The priority conditions to be addressed initially by mhGAP were: depression, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, suicide, epilepsy, dementia, disorders due to the use of alcohol, disorders due to the use of illicit drugs, and mental disorders in children. In 2013, conditions specifically related to stress were added to this list. The WHO developed an intervention guide presenting separate modules for each of these conditions. It comprises protocols for clinical decision-making in integrated management.³ It was developed through a systematic review of evidence, followed by an international consultative and participatory process in which numerous experts from all over the world were involved. The selection process took the balance of benefits and harm into consideration, as well as value judgments (e.g. protection of human rights), resource use, and feasibility (availability of lab etc). The WHO suggests mental health workers in LMIC to conduct a situation analysis, identify local priorities and barriers to scaling up services, and to adapt the mhGAP Intervention Guide accordingly.

For two reasons it is quite remarkable that in the mhGAP Intervention Guide only evidence-based treatment methods are mentioned. Firstly, it is in line with the view that in LMIC, like in higher-income countries, no methods should be applied which have no proven effectiveness. This seems obvious, but unfortunately daily practice in LMIC is different, and understandably so. Secondly, it is in full concordance with the assumption that most conditions of this kind can be managed by non-specialists, a statement which western mental health professionals could consider as provocative in itself.

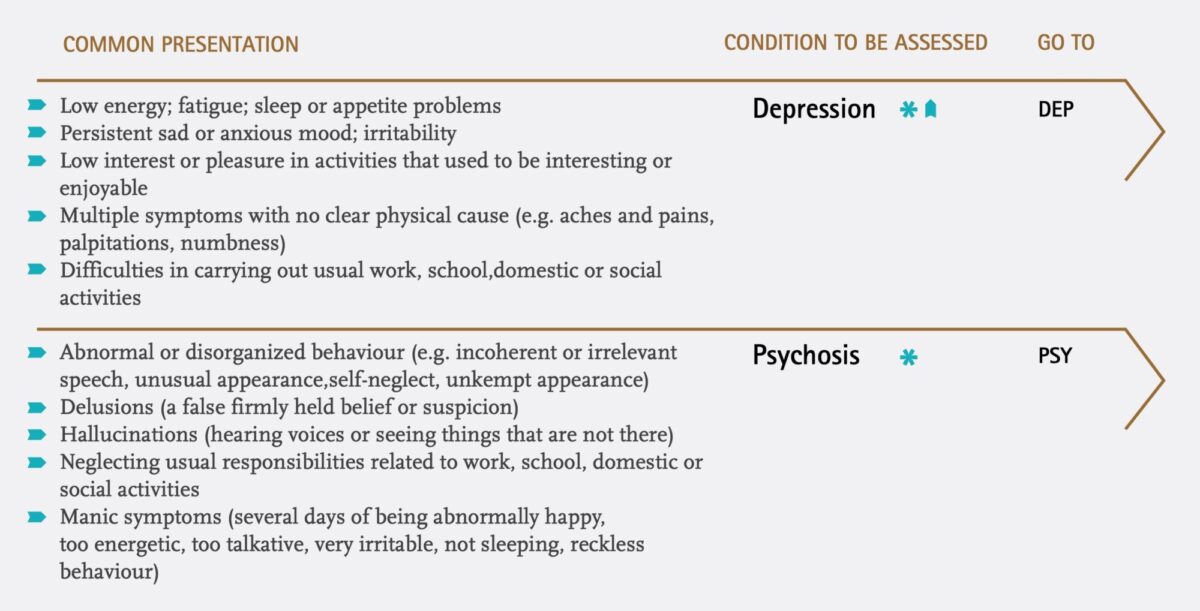

As if the editors wanted the Guide itself to underline this statement, its design is a soon to be classical example of user-friendliness. The health worker is first guided through a Master Chart listing the common presentations of all established priority conditions. As an example, figure 2 shows the Depression and Psychosis sections of this Master Chart. If features of one condition are present, the condition should be assessed; the worker is then guided to the module addressing that condition.

(Source: mhGAP Intervention Guide. Geneva: WHO)

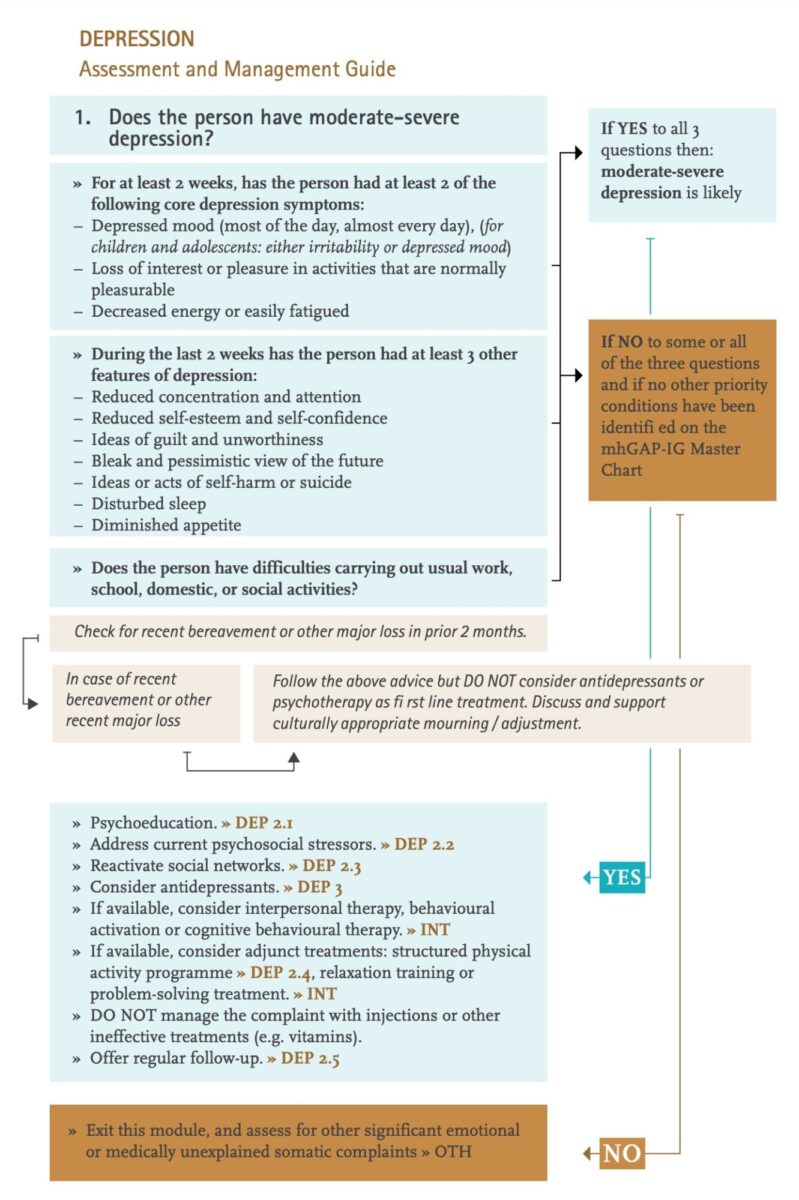

All modules consist of two sections. In the first section the ‘assess column’ clearly lists a condition’s diagnostic criteria. If criteria are met, the condition in question is likely to be present. The worker is then guided to the ‘manage column’, in which advice on psychological and psychopharmacological interventions is given. Figure 3 shows the first page of the Depression module as an example.

(Source: mhGAP Intervention Guide. Geneva: WHO)

In the flowcharts, relevant intervention details are identified with codes, guiding the worker to corresponding parts in the second section of the module. There, more information is provided on follow-up, referral, relapse prevention, more technical details of treatments, and important side effects and interactions of medication.

The guide presents a special section on ‘advanced psychosocial interventions’. This term refers to interventions which are more complex and take more than a few hours to learn and also to implement. The mhGAP considers application to be possible in non-specialized care settings, provided that sufficient human resource time is available. Analogous to how professionals may be unhappy with the management of serious mental health disorders by non-specialists, one may argue that certain psychotherapeutical methods are not suitable for application by relative laymen. For example, in the western world professionals are only allowed to learn ‘eye movement desensitization and reprocessing’ (EMDR) or ‘trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy’ (TF-CBT) if they have a certain advanced degree in the mental health field. One may ask why to put such criteria aside when dealing with health workers in LMIC. On the other hand, one may also suspect/suppose paternalism in the stance to decline the transfer of such skills when there is a real demand.

The WHO has obviously made a remarkable move, not only by stating that the existing treatment gap in LMIC should be overcome by introducing easy-to-implement treatment methods. It has also decided that most evidence based treatment methods are easy enough to be implemented by non-specialists, and that therefore knowledge on evidence-based treatment methods should be – and can be – transferred to health workers in LMIC. I believe that with this publication the WHO has provided an extremely easy-to-handle high quality intervention guide.

The WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide can be dowloaded from:

www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mhGAP_intervention_guide

References

- http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap

- WHO (2011). The mental health workforce gap in low- and middle-income countries: a needs based approach. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89, 184-194.

- WHO (2010). mhGAP Intervention Guide for mental health, neurological and substance abuse disorders in non-specialized health settings. Geneva: World Health Organization.

References editorial

- Carothers J C. The African mind in health and disease: A study in ethnopsychiatry. World Health Organization; 1953.

- World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013-2020. World Health Organization; 2013.