Main content

Epidemiology

In May 2015, locally acquired cases of Zika virus infection were confirmed in Brazil. Since then, the virus has spread to more than 25 countries in the Caribbean, North and South America. WHO/ PAHO have warned that the virus is likely to spread across nearly all of the Americas due to a lack of any natural immunity. They added that the vector, Aedes mosquitoes, is present in all countries of the region, except in Chili and in Canada.

A decade ago, confirmed cases of Zika virus infection from Africa and Southeast Asia were rare, and until recently there has not been much published on the virus. In 2007 the virus hit Yap in Micronesia, and via French Polynesia and other Pacific islands in 2013 it arrived – most probably via Easter Island – in Brazil in 2014, and in 2015 in Colombia and in Surinam.[2,3,4,5] Cape Verde in Africa reported a Zika virus outbreak in 2015 as well.

Infection with Zika virus has been linked to newborn babies with congenital microcephaly. It is presumed to be responsible for Guillain-Barré syndrome and other neurologic conditions such as 73 cases in a population of 270,000 in a French Polynesian epidemic in 2013.[6,7]

Zika virus

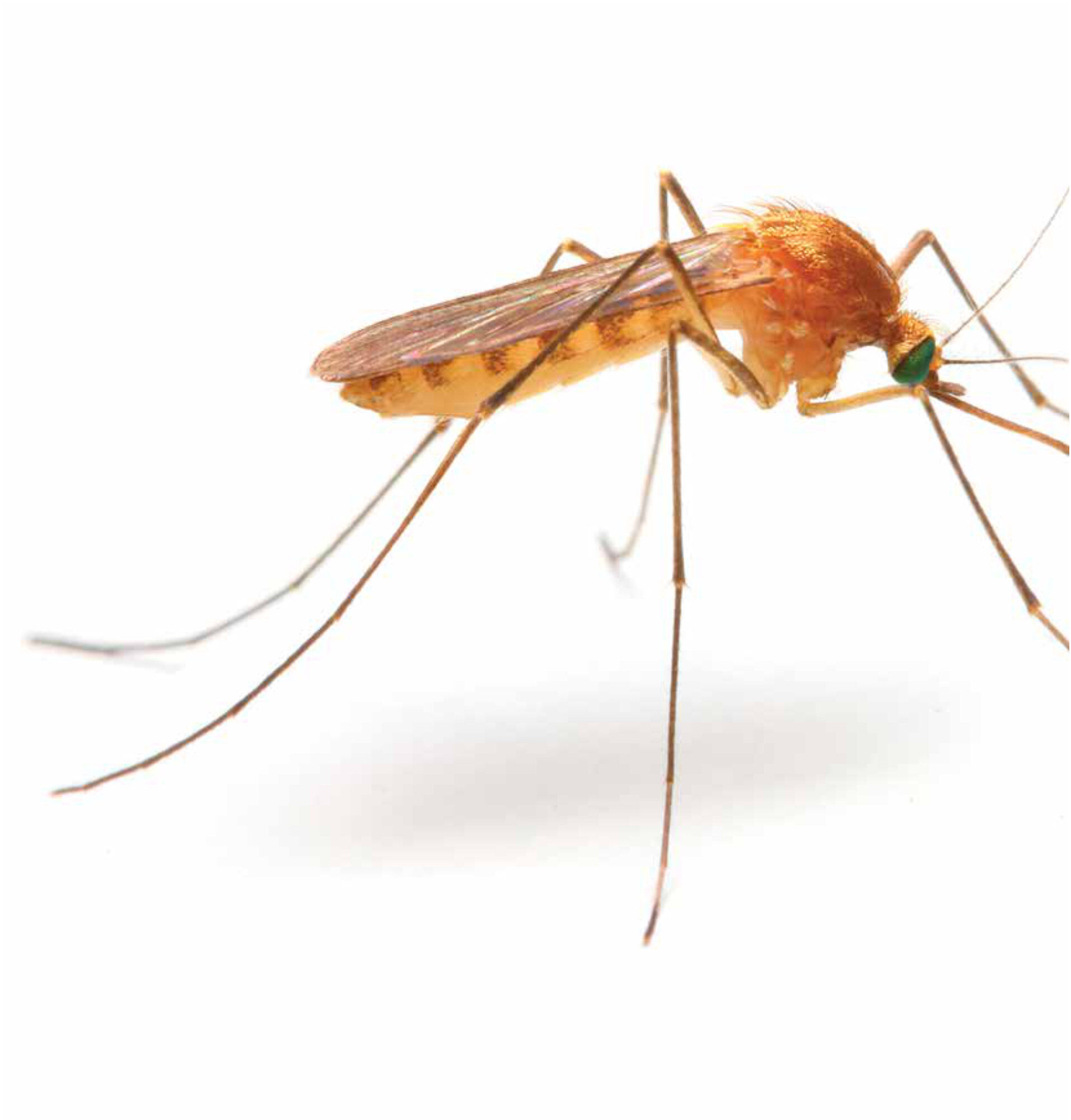

The Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne arbovirus belonging to the family of flaviviridae, native to Africa or Asia, and transmitted via Aedes mosquitoes, such as A. aegypti – the same mosquito that transmits dengue, chikungunya, West Nile virus and yellow fever.[8] The virus was first isolated from a rhesus monkey in Uganda in the Zika forest in 1947, and it was first described in 1952 by Dick et al in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene.[9] The infection has a short incubation time of a few days and causes mild fever, conjunctivitis, skin rash and headache (sometimes called dengue-light). These symptoms normally last for 2-7 days. Around 80% of Zika virus infections in individuals are asymptomatic. Usually hospitalization is not necessary and mortality is extremely rare.

Transmission

Aedes mosquitoes transmit Zika virus; evidence about other transmission routes is limited. Spread of the virus occurs through blood transfusion, but cases of transmission through sexual contact have also been reported.[10] Zika virus has been isolated in human semen, and one case of possible personto-person sexual transmission has been described. Standard precautions that are already in place for ensuring safe blood donations and transfusions should be followed.

Evidence on mother-to-child transmission of Zika virus during pregnancy or childbirth is limited. A mother already infected with Zika virus near the time of delivery can pass the virus on to her newborn around the time of birth, but this is rare. It is possible that Zika virus could be passed from a mother to her baby during pregnancy. Research is needed to generate more evidence regarding perinatal transmission and to better understand how the virus affects babies. There is currently no evidence that Zika virus can be transmitted to babies through breast milk. Mothers in areas with Zika virus are advised to follow the PAHO/ WHO recommendations on breastfeeding: exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, followed by continued breastfeeding with complementary foods up to 2 years or beyond.

Diagnosis, prevention and treatment

Zika virus is diagnosed through PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and virus isolation from blood samples. Diagnosis by serology can be difficult as the virus can cross-react with other flaviviruses such as the ones responsible for Japanese encephalitis, dengue, West Nile virus infection and yellow fever.

The most effective forms of prevention are reducing mosquito populations by eliminating their potential breeding sites, especially containers and other items such as discarded tires that can collect water in and around households and in particular using personal protection measures to prevent mosquito bites.

Zika virus disease is usually relatively mild and requires no specific treatment. People sick with Zika virus should get plenty of rest, drink enough fluids, and treat pain and fever with common medicines. If symptoms worsen, they should seek medical care and advice.

International response and implications

The virus is currently spreading rapidly with more and more countries in the Americas reporting cases. Some countries advise women not to get pregnant, while in others women are advised not to travel to regions or to countries where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. The Americas, Europe and Asia receive the most travellers who depart from Brazilian airports internationally. It is obvious that with no vaccine or antiviral therapy available Zika’s rather disturbing march may not stop in the Americas. A recent article in the Lancet highlights the potential of Zika virus to follow dengue’s and chikungunya’s global spread.[11]

In the Netherlands, Zika virus infection has been diagnosed in people who contracted the virus outside the country.[12] At the time of this writing, a total of twenty-three travellers got infected in Surinam. The spread of Zika virus within the country is most unlikely because of a lack of the Zika virus vector in the Netherlands.

The WHO, through its emergency committee on Zika virus, has declared the virus a public health emergency of international concern since a causal relationship between Zika virus during pregnancy and microcephaly is strongly suspected although not yet proven. WHO urges better coordination of the international efforts to investigate and thus understand the relationship better. Improving surveillance and diagnosis of infections is needed to detect congenital malformations and neurological complications earlier. Furthermore, stricter control of mosquito populations is needed, as well as the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines for protection of non-immune individuals.[13] With the summer Olympics in Rio fast approaching, lessons from countries with success in controlling pandemics should be learned, for example Saudi Arabia’s success with hosting Umrah and Hajj and others with controlling outbreaks of influenza A H1N1, MERS, and Ebola. In the months ahead, Brazilian and Saudi authorities will have the opportunity to review emerging research findings on the natural history of Zika virus. Proactive planning and preparedness will mitigate the effect of Zika virus infection on mass gatherings, participants, and their home and host countries, so that the events can be held with a sense of confidence among all those involved, including organizers as well as participants and the global community.

Based on the available evidence, WHO is not recommending any travel or trade restrictions related to Zika virus disease. Women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant must determine the level of risk they wish to take with regard to Zika and plan accordingly. In particular, they should:

- stay informed about Zika virus and other mosquito-transmitted diseases;

- consider delaying travel to any area where locally acquired Zika infection is occurring;

- protect themselves from mosquito bites (see above);

- consult their doctor or local health authorities if travelling to an area where Zika virus is present;

- mention their planned travel during their antenatal check-ups; and, upon return, consult with their healthcare provider for close monitoring of their pregnancy.

Until more is known about the risk of sexual transmission, all men and women returning from an area where Zika virus is circulating – especially pregnant women and their partners – should practice safe sex, including the correct and consistent use of condoms.[14]

References

- WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record (WER) no 45, 2015, 90: 609-16. http://www.who.int/wer

- Duffy MR, Chen T-H, Hancock WT et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 2536-43.

- Musso D, Nilles EJ, and Cao-Lormeau VM. Rapid spread of emerging Zika viruis in the Pacific area. Clin Micrbiol Infect. 2014; 20: 595-6.

- Zanluca C, de Melo VC, Mosimann AL, Dos Santos GI, Dos Santos GN, and Luz K. First report of autochtonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015; 110 :569-72.

- Enfissi, Antoine et al. Zika virus genome from the Americas. The Lancet, Volume 387, Issue 10015, 227 – 228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00003-9

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. ZIKV virus epidemic in the Americas: potential association with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome [Internet]. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015 [cited 2015 Dec 10]. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/ZIKV-virus-americas-association-with-microcephaly-rapid-risk-assessment.pdf.

- Fauci, Anthony S.; Morens, David M. (14 January 2016). “ZIKV Virus in the Americas – Yet Another Arbovirus Threat”. New England Journal of Medicine 374 (2): 160113142101009. doi:10.1056/NEJMP1600297. PMID 26761185

- Zika virus infection. www.ecdc.europa.eu. Accessed 3 February 2016

- Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. ZIKV virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1952; 46:509-20

- Foy, B. D.; Kobylinski, K. C.; Foy, J. L. C.; Blitvich, B. J.; Travassos Da Rosa, A.; Haddow, A. D.; Lanciotti, R. S.; Tesh, R. B. (2011). “Probable Non-Vector-borne Transmission of Zika Virus, Colorado, USA”. Emerging Infectious Diseases 17 (5): 880-2.

- Musso, Didier et al. Zika virus: following the path of dengue and chikungunya? The Lancet, Volume 386, Issue 9990, 243 244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61273-9

- Goorhuis A, von Eije KJ, Douma RA, Rijnberg N, van Vugt M, Stijnis C, Grobusch MP, Zika virus and the risk of imported infection in returned travelers: implications for clinical care, Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease (2016), doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.01.008.

- WHO. WHO statement on the first meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR 2005) Emergency Committee on Zika virus and observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations. Feb 1, 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/1st-emergency-committee-zika/en/ (accessed Feb 3, 2016).

- http://www.who.int/csr/disease/zika/information-for-travelers/en/, accessed 13 February 2016.