Main content

Can you imagine working on a very busy labour ward, with an average of 30 births per day without enough colleagues and training? And a high level of complicated deliveries, preterm deliveries and a high incidence of severe congenital malformations, resulting in a high case load of babies with (severe) asphyxia, prematurity, sepsis and major congenital malformations? Before 2015, the care of these patients in Sengerema Hospital in rural Tanzania was insufficiently organized and no formal neonatal care department existed, contributing to high neonatal mortality rates of 17%.[1] Through a strong collaboration between Sengerema Hospital and the Friends of Sengerema Hospital Foundation, which continues to this day, the perspectives for this vulnerable group improved.

| Neonatal mortality Netherlands: | 1.7 / 1000 (2021) [2] |

| Neonatal mortality Tanzania: | 19 / 1000 (2020) UNICEF data warehouse [6] |

| Deliveries on a yearly base Sengerema: | 6867 (2022) annual report Sengerema Hospital [1] |

| Mortality rate NICU Sengerema 2014: | 89 / 509(17.5%) annual report Sengerema Hospital [1] |

| Mortality rate NICU Sengerema 2022: | 92 / 1571 (10.5%) annual report Sengerema Hospital [1] |

| Admissions NICU Sengerema in 2022: | 1571 annual report Sengerema Hospital [1] |

Background

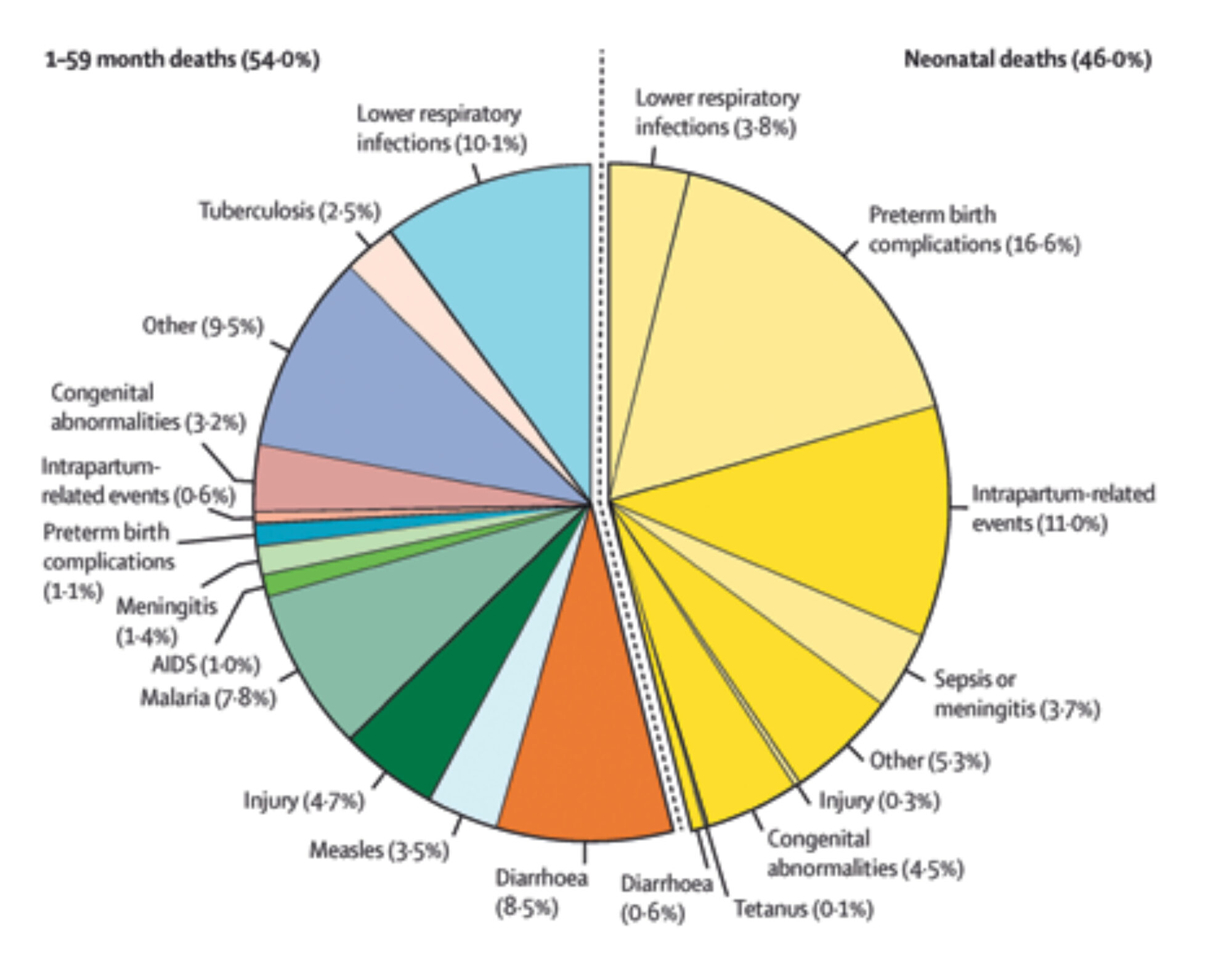

Sengerema is a poor and rural region in the northern part of Tanzania with a population of more than 700,000 people. Nowadays the district hospital is developing into a referral hospital and seriously investing in maternal, perinatal and neonatal health care. With a neonatal mortality rate ten times higher than the Netherlands [1-2] (Table 1), the inequality in health remains enormous. A systematic analysis in 2019 shows a high percentage of neonatal mortality among child mortality in limited settings [3] (Figure 1). In line with the sustainable development goals (SDGs), one of the main focuses of Sengerema Hospital is to reduce neonatal mortality.

Improving neonatal care

The management of the hospital and Dutch medical volunteers of the Friends of Sengerema Hospital Foundation developed a plan to invest in perinatal and neonatal care. As a result, project Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) was ‘born’ in 2015. With an average of 7,000 deliveries on a yearly basis, the idea was to open up a unit for essential newborn care. Besides setting up a neonatal ward, it was also important to compose a dedicated NICU team. By working closely with the nurses and doctors at the wards, but also with the district health officer from the local government, a team was formed with the motivation, spirit and skills to start this project. A training adjusted to the context and their prior skills equipped them with the essential knowledge and skills to provide appropriate care for the most vulnerable period in a newborn’s life. The full NICU staff was trained before the official opening of the unit in November 2015.

Incremental steps in improving care

During the first year, the main focus was on creating the physical NICU, training of the new NICU staff, and implementation of the protocols based on the ‘National guideline for neonatal care and establishment of neonatal care unit’.[4] This high-level unit started with four incubators, oxygen machines, two resuscitation tables, and some monitors. The local team was very dedicated and enthusiastic. During the first months of the training, the main focus was on neonatal resuscitation after birth. Guidelines and a training program of Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) were used as a basis and were provided through simulation-based training. This program teaches the skills of caring for healthy babies and assisting babies that do not breathe on their own after birth. Large-scale studies showed that HBB programs led to a 47% reduction in early 24-hour neonatal mortality in Tanzania.[5] Continuous bedside training was provided to allow the team to learn new skills and grow into their role with increased responsibilities. The results within the first year were incredible. There was a decrease in neonatal mortality of 40%.[1] With the complete NICU training, the local team achieved a lot. With the increasing pride of the team, the dedication and enthusiasm to take care of the most vulnerable patients in the hospital grew. Due to continued support and guidance over the seven and a half years that followed the opening, the local team was able to grow further and new interventions like Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) were introduced.

Pitfalls and challenges

Of course, opening this brand-new unit was not only a success. Especially in the beginning, there were some pitfalls and unexpected events. The capacity of the old generator was not sufficient after installing all the new medical equipment. The increased use of power increased the energy costs by 25% after opening the NICU – a wry twist considering that the NICU does not generate any income, since the care is offered free of charge.

High turnover of health care workers in rural Tanzania is a common threat to continued care. This makes it extremely challenging to build a team and increase capabilities and skills. Nurses are often placed in different wards or are relocated to different health facilities. In addition, the emotional, cognitive and physical burden on the nurses is significant, at times impacting their motivation and willingness to work on the NICU. Discussing this with the team as well as hospital management was essential for success. It showed once again that regular retraining and intervision are needed for new staff members.

Financial sustainability is a serious challenge in this setting. Funding some of the (recurring) costs through donations allows a standard of care for newborns – care which would not be provided were it only to come from the regular financial resources of the hospital. To date, Friends of Sengerema Hospital Foundation pays for approximately 25% of the recurring costs of the facility. Stopping this support would immediately threaten the continued future of the project.

Miracle babies

The NICU has now been running for seven years. With an average of 1,500 annual admissions, there was a serious need to expand the unit and hire more staff. After raising the appraised financial support, the NICU underwent a complete renovation in 2022. The team designed the new unit themselves, according to their wishes and latest standards. The unit now can offer an even higher level of care as there is more and improved medical equipment.

The complete staff was trained on a daily basis for four months after the opening of the renovated NICU. Ever since, our local colleagues have reported additional unexpected successes. Some babies with a birth weight of only 500 grams survived without invasive ventilation, endotracheal surfactant and, for example, a peripherally inserted central catheter for parenteral nutrition. They survived as a result of very dedicated nurses who supported the kangaroo mother care: skin-to-skin contact with the baby for the greatest part of the day, which is the best and most incredible ‘medicine’ for preterm babies in low-resource settings.

In other parts of Tanzania, initiatives to start an NICU have arisen. Colleagues from other hospitals visit Sengerema Hospital to follow accredited trainings on neonatal care. In addition, these trainings provided by the local staff and members of the Foundation generate income for the hospital.

Lessons learned

- Keep it simple and focus on the basics. Make sure that the interventions you propose are feasible, acceptable and sustainable. Only add new things when the basics are going well.

- The right team is essential for success. Cherish them and let them grow and make sure you keep an eye out for their needs.

- Bedside teaching, long-term involvement and support are key for success and sustainability.

- Local ownership and engagement of leadership are essential to ensure buy-in, especially since neonatal care is usually an activity that does not generate income.

- In case of projects that are (partly) financed by external parties, be prepared to invest in a sustainable plan that focuses on local ownership.

With special thanks to Niek Versteegde, Rian Jager and Sandra Zoetelief (Friends of Sengerema Hospital Foundation)

References

- Voeten, M. Annual report Sengerema Designated District Hospital 2014 – 2022

- Perined. Kerncijfers geboortezorg 2021. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.perined.nl/onderwerpen/publicaties-perined/kerncijfers-2021 [Accessed 8th march 2023]

- Perin J, Mulick A, Yeung D et. al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. Volume 6 2022; 6: 106–15

- Ministry of health of the United Republic of Tanzania. National guideline for neonatal care and establishment of neonatal care unit. 2019 August.

- Laerdal Global Health. Helping Babies Breathe 2001-2023. [Internet]. Available from https://laerdalglobalhealth.com/partnerships-and-programs/helping-babies-breathe/. [Accessed 28th march 2023]

- Unicef. Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities 2015. [Internet]. Available from https://data.unicef.org/country/tza/. [Accessed 2nd April 2023]