Main content

The old ’86 Land Cruiser is hesitating. The thick layer of dust on top testifies that the previous trip with so called ‘Victor’ has been a while ago. Finally, it starts and the garage of the hospital is filled with black smoke. It is 7 a.m. Ecuadorian time in Puerto el Carmen, the sun is already quite high, and since we’re right on the equator, you can already feel it burning on your skin.

Outside we expect to meet Carlos, the head of the boat park of the local municipality. He will be our boat driver today to go to Tres Fronteras, a little village downstream where the borders of Peru, Colombia and Ecuador meet. However, when he arrives, he informs me that the boat we reserved a week ago is unavailable today. Normally, the mayor is willing to lend one of his boats since our aim is to improve health in his communities. You do have to ask him formally though, and in duplicate. And not on normal paper, but on paper they sell at a desk hidden downstairs in the municipality. But even after jumping through these hoops, a guarantee you will never get.

The good news is that today we will go with the ‘limousine’, a fast boat that normally only the mayor and his people use. With its two hundred horsepower, the outlook for the day is suddenly looking much more attractive. A four-hour drive one way is now reduced to one and a half hour one way, meaning more time available to attend to the people in Tres Fronteras. The only way to reach Tres Fronteras is over the Putumayo River which forms the natural border between Colombia and Ecuador. It is a red zone in which armed groups have been active for many decades. They do not allow traffic on the Putumayo River after sunset. Leaving before 6 a.m. and coming back after 6 p.m. is out of the question. Due to these hazards, the Ecuadorian marine, which like the army has a large base in Puerto el Carmen, wants to know who is leaving with which boat and where to: another permit that had to be arranged.

The disadvantage of a faster boat is that it uses a lot more gasoline. And since the outboard motors of the limo are outdated, you have to mix the gasoline with engine oil yourself. Carlos climbs into the passenger seat of old Victor and first we go to the workshop of the municipality to get empty jerrycans. The only gas station in town opens at 7 a.m. and when we arrive around 7:30 a.m. there is already a long line of people with small jerry cans who came on foot or by boat. They are all lined up to one pump; the other one is for cars, luckily. To prevent a lot of gasoline ending up on the Colombian side of the border, where gasoline is much more expensive, you need a permit to buy large amounts of diesel or gasoline on the Ecuadorian side of the border. Permit checked and approved, the hose goes into the first jerrycan to start pumping the three hundred litres of gasoline. Meanwhile there is time to buy the engine oil. “5 1/4’s” were the instructions of Carlos, deciphered as five times a quarter of a gallon, meaning five litres. We need to stop by two shops, as the owner of the first shop pretends not to have this type of oil – perhaps not willing to sell to this bearded ‘gringo’?

In a mix of gasoline fumes coming from Victor’s carburetor in the front and the filled jerry cans in the back, we drive back to the shore of the river just beside the hospital. The low water level exposes the destruction of the riverbanks during last rainy season. The old boarding school which is now housing Hospital San Miguel is built right on the riverbank where the San Miguel River and Putumayo River merge and bend. The result of this bending is that the flow of water is always pushing against the river banks, day and night. The wall that was built to protect the village is sinking slowly but surely back into the river. Stairs, structures on top of this wall, everything is going down. Massive amounts of concrete reinforced with impressive rebar just cracks as if made from glaze, testifying that nature, in the end, always wins.

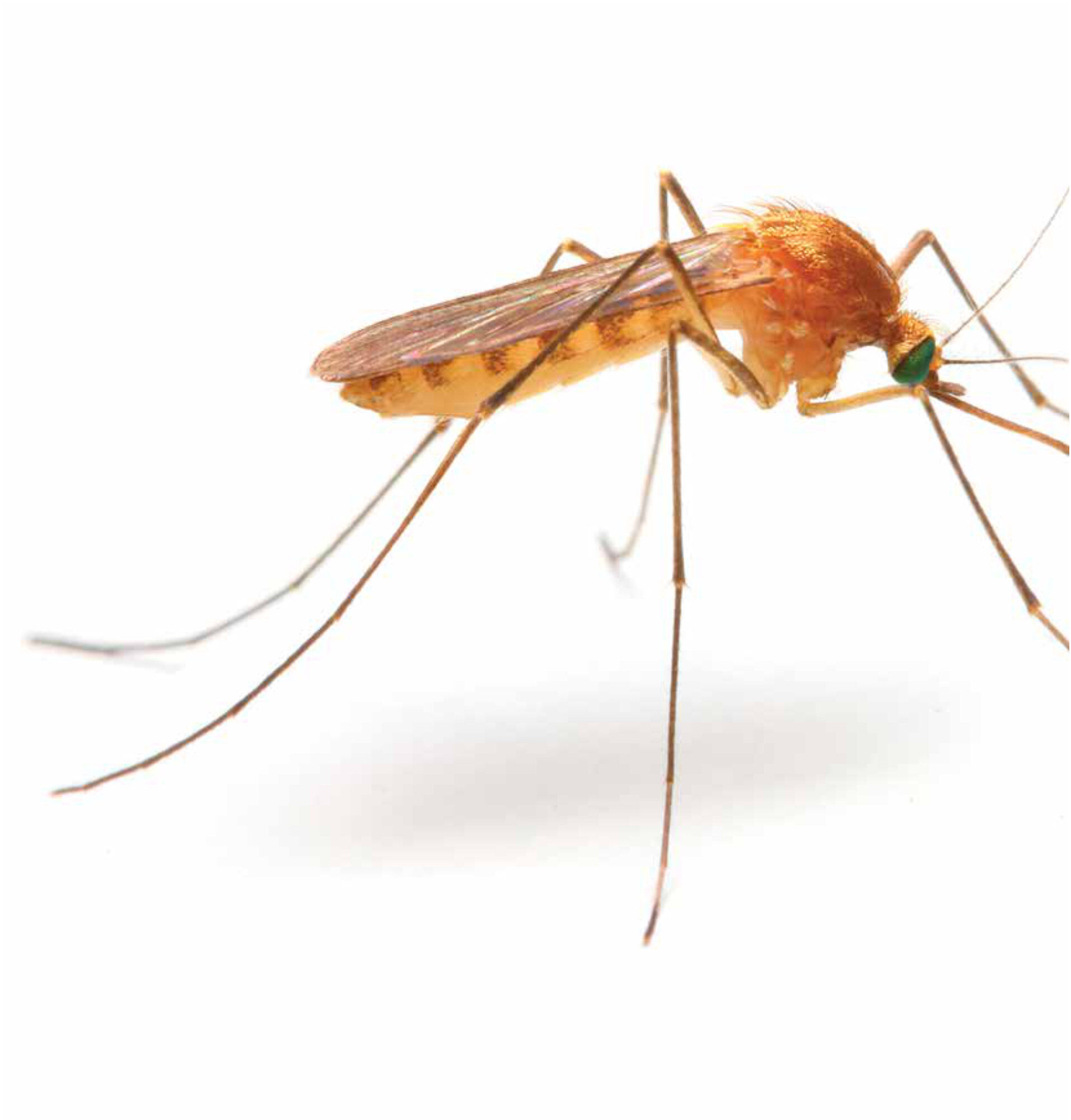

The jerrycans with gasoline are dragged down to the boat, together with the crates and coolers from the hospital containing medicines and supplies, printed informed consents, laptops and, of course, lunch. The main reason for the visit today is a research project funded by the Otto Kranendonk Fund (OKF), which aims to demonstrate the prevalence of malaria within the Ecuadorian Putumayo. Putumayo is a local district within the Sucumbíos province, inside the Ecuadorian Amazon basin. With respect to infectious disease, this is tierra incognita. No data is available on prevalence of disease or presentation of symptoms nor data on convalescence. For this research project, at three different moments throughout the year to include seasonal influences, three different communities throughout Putumayo are visited: one far upriver, one far downriver, and the third in Puerto el Carmen itself. Today will be the second visit downriver, after having visited these sites earlier in May this year.

That we’re facing a reduced travel time becomes evident when Carlos opens the throttle. Due to its speed, the boat lifts itself out of the water, further reducing resistance. At a speed of 50-60 km/h you feel like flying. The scenery that rushes by is just amazing: on the riverbank, lush green jungle with now and then a large ceibo tree towering above the canopy. Little wooden houses looming between the trees. The intense sunlight seems to bleach out the poverty of the circumstances in which people are living here. You almost start thinking that it is not the worst place on this planet to wake up every day.

This thought evaporates instantly once you put a foot on the community ground of Tres Fronteras. Though we announced our visit beforehand through a contact of a contact of a contact, people only arrive at community house – where we’re holding office for the day – once they’ve heard through another contact of a contact that the announcement was true. The difference between Puerto el Carmen and Tres Fronteras is stunning. Most people are in rags and often without shoes. Children look malnourished and unhealthy. Contact with the inhabitants is much more rigid than we’re used to. They clearly don’t trust us, most likely because they think we’re North Americans and suspect we may have other intentions. It wouldn’t be the first time someone thinks we’re spying for the DEA. We start unpacking and set up our ‘laboratory’ and ‘sampling area’. Today we’re offering both a rapid diagnostic test for malaria and for dengue, for which we have to draw one tube of full blood from each participant. Adult women are also offered sampling with a vaginal brush for a molecular assay of human papilloma virus (HPV), analysed upon arrival in our laboratory.

While we unpack, somebody asks if we can take a look at Don Agusto. It appears that he has been sick already for eleven days and is confined to his bed. We follow them to the ‘house’ of Agusto, a small wooden shed on poles just on the side of the river where we got out of the boat. Getting closer to the shed we hear groaning. The only way up is by climbing on a tree trunk with carved out steps. In ten years working abroad in low- and middle-income countries, I’ve seen quite some misery, but finding Agusto there, on top of a worn-out mattress, surrounded by garbage, damaged tools and some burnt out candles, did truly hurt: conditions so inhuman that I would have preferred to pick him up, carry him to our boat, and take him straight to our hospital. Unfortunately, things are managed differently here.

Agusto was burning up from fever and having the diagnostics available, we did a bedside malaria and dengue rapid test: both negative. Without having properly eaten for more than a week and living on coca cola, we knew there was not much time. Without permission of the president of Tres Fronteras there was no way of taking Agusto back to Hospital San Miguel. We just got to know the president when we arrived, a very reasonable man with, as a first impression, good intentions for his people. But he can’t decide on his own. Agusto’s sister appears not to be in favour of the evacuation of her brother. Even after promising her that they won’t need to pay anything, they can leave whenever they want, she still refuses.

We decide to continue with what we came for: sampling for the combined malaria/dengue study and HPV. After an extensive explanation of the objective of our visit and a short introduction of everyone on our staff, I take a seat on a very small primary school chair behind an even smaller primary school desk. One by one the people come and sit in front of me, and I explain, again, what our objective is and ask if they are willing to participate. If so, they sign with a signature or, more often, with their fingerprint. Then they move to the ‘sampling area’, which is just the chair next to them, and from there the blood goes to the ‘laboratory’ – all within 10 square metres. As time passes, the atmosphere changes a bit. We bring stickers and little crocheted octopuses as toy dolls for the kids, and share our homemade bread with the elderly. Little by little, the people start talking, ask us questions, and start to make jokes (most likely about us).

Close to 3 p.m. it’s already time to go back to Puerto el Carmen. The decision regarding Don Agusto unfortunately has not changed, but at least they reveal the real reason for refusing to come with us: they first want to take Agusto to the shaman, a local traditional healer. If that doesn’t make him better, they promise to bring him to Hospital San Miguel for further treatment. We get into our boat, happy with the forty samples we were able to take but sad for leaving Agusto behind, and head back to Puerto el Carmen.

A few days later, our receptionist calls me: the family of Don Agusto is standing in front of her, asking if we can lend them our stretcher to carry Agusto from the river to the hospital.