Main content

The recent inclusion of high-priced patented cancer medicines on the World Health Organization (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) has changed the landscape for access to essential medicines as a human right. Even wealthy governments in the North are struggling with the paradox that whilst some new medicines are considered essential (i.e., they have been judged to provide significant therapeutic advantage by the EML expert committee), they are also unaffordable. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) the situation is even worse. Whilst essential treatments should be made available, the burden on governments and on the patient, who generally has to (co)pay for treatment, means they are simply out of reach. This paper takes the example of sofosbuvir (Sovaldi®) in Europe, an on-patent essential treatment for hepatitis C, which was added to the EML list in April 2015, to examine price differences between countries.

Assessing access to medicines

The current model of equal access to medication for patients throughout Europe is becoming unsustainable. Demand for treatments is increasing, mainly due to an ageing population, the growing chronic disease burden and new developments, such as personalized medicines and technologies(1). At the same time, the price of new medicines is rising rapidly. High demand is therefore compounded and exacerbated by high medicine prices. For example, expenditure on pharmaceutical treatments in EU countries rose by approximately 76% between 2000 and 2009(2) and remains a grave concern across the EU (3). This poses a massive burden on health systems, already compromised by the recent economic crisis (4).

Through quantitative and qualitative research, the two main dimensions of access to medicines, affordability and availability(1), were assessed in four European countries: Spain, France, Austria and Latvia. Official hospital prices of five selected medicines were related to national gross domestic products (GDP) per capita and purchasing power parity (PPP) to assess affordability. Semi-structured interviews with key informants from each country were conducted to gather information on availability and affordability of the selected medicines for the in-patient sector. (2)

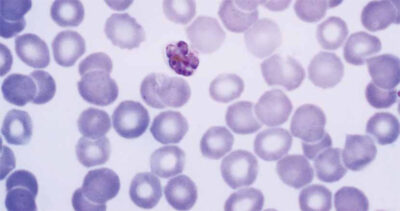

Approximately 130 to 150 million people suffer from chronic hepatitis C infection worldwide. Approximately 500,000 people die each year from hepatitis C-related liver diseases (5). In 2012, more than 30,000 cases of hepatitis C were reported in 27 EU countries(6). Amongst the treatments recently available on the market, sofosbuvir, marketed by Gilead as Sovaldi®, was granted a marketing authorization valid throughout the EU in January 2014(7).

Having collected the unit prices (3) in the four selected countries, data were analysed, compared in nominal value(4) and adjusted by the countries’ purchasing power parity (PPP) to ensure that the prices of medicines are valued similarly and provide an affordability estimate. The PPP adjusted price was calculated by using the PPP conversion factor from Eurostat (2013). The table below shows the price differences between the EU Member States. Latvia, although having the lowest annual GDP per capita, is paying the highest price for sofosbuvir.

Government’s responses

Sofosbuvir is not on the list of medicines that are reimbursed by the state insurance scheme in Latvia. In the interviews, informants blamed the lack of government-sponsored access on its unaffordable and very high price. Therefore, patients are forced to cover costs for the treatment themselves out-of-pocket.

Sofosbuvir is reimbursed, however, in Austria, France and Spain, albeit on a case-by-case ‘restricted procedure’ basis. A restricted procedure means that patients must fulfil defined country-specific clinical eligibility criteria to obtain treatment reimbursement. Interview respondents confirmed the considerable contrast of the hospital availability and reimbursement status of high-priced medicines between Latvia and the other countries.

In all the countries studied, the lack of price transparency and collaborative efforts for procurement, in particular between the out-patient and in-patient sector (hospitals and pharmacies), were repeatedly highlighted by interview respondents as posing a barrier to access.

| Country | GDP | Strength | Unit Price per pill | Price per treatment | PPP conversion factor | GDP/price ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 38,100 | 400 mg | 488.10 | 41 000.4 | 1.11761 | 1.28% |

| France | 32,100 | 400 mg | 488.11 | 41 001.24 | 1.13105 | 1.52% |

| Latvia | 11,600 | 400 mg | 733.02 | 61 573.68 | 0.679363 | 6.32% |

| Spain | 22,500 | 400 mg | 465.12 | 39 070.08 | 0.900630 | 2.07% |

Source: GDP, PPP conversion factor data from 2014, Eurostat. Price data surveyed by the authors as of May 2015.

Conclusions

Overall, national strategies to lower prices for medicines were perceived by informants as insufficient and not tackling core issues, such as the need to increase price transparency and improve cooperation in the management of hospital procurement. The in-patient sector still represents a black box for policy makers in that it remains unknown what hospitals pay for the medicines they purchase.

The lack of transparency on hospital prices, actual transaction costs and consumption can increase difficulties for governments to respond appropriately to increasing costs for medicines and to the public health needs of their population. The example of sofosbuvir reflects the increasing issue of unaffordability of medicines for European countries. To tackle this issue, which is expected to be no different in low- and middle- income countries, increased transparency for prices of medicines in the in-patient sector is needed. Therefore, hospitals’ pharmaceutical expenditure and consumption at national and international levels should be surveyed. National and EU strategies to ensure equal access to high-priced medicines also need to be developed.

Discussion

As this review implies, the pharmaceutical industry acts according to its own strategy, which results in significant prices differences between member states (tiered pricing). These price inequalities do not reflect any rational financial constraints on the health systems, since the member state with the highest procurement price (Latvia) has the lowest GDP.

The pharmaceutical industry justifies its high prices by claiming it makes large investment in research and development (R&D), but the truth is that no one knows how much is spent on the development of a new drug, and estimates by the industry and independent analysts vary greatly. (8, 9) In any case, R&D costs should not be the major driver when it comes to pricing(5). The added value that the medicine brings to patients and healthcare systems should also be taken into account. The issue of transparency is core here, as citizens have a right to know what public money is being spent on.

At the international level, the harmonized standard of intellectual property protection laid down in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) permits EU member states to issue a compulsory license to ensure affordable access to medicines for their citizens(10). By issuing a compulsory license, a government authorizes the production and marketing of a cheaper generic version or versions of a patented medicine on the condition that authorized generic firms pay a license fee to the patent holder. A compulsory license, or even the mere threat of issuing one, may result in a substantial decrease in the price of a medicine.

The recent patent opposition of Sovaldi® by Médecins du Monde in France paves the way to another policy option. By breaking the monopoly situation, generic competition has proven to be an effective way of lowering medicine prices and delinking the price of a medicine from its R&D costs.

In addition to the urgent short-term need to address the high cost of medicines, deep reforms of the R&D model and greater transparency are needed to respond to the global challenge of access to medicines from a long-term perspective. A strong political commitment is, however, a prerequisite.

Notes

(1) In this study, affordability is defined as the extent to which national health insurance schemes are able to cover the costs of the medical needs of patients within the available health budget. Individual affordability is linked to the financial burden of cost-sharing (Kanavos et al., 2011a). Affordability is therefore the relationship between the monthly drug regimen cost and GDP per capita. This indicator can be used as a reference point for cross country comparison to analyze the cost of treatment option for different Member States (Günther et al., 2014). Availability is taken to mean the medicine of choice is available to the practitioner and patient, unaffected by the government or health facilities ability to procure it.

(2) Full report forthcoming 2015.

(3) Prices of all available strengths and package sizes of the five selected active ingredients were surveyed. For subsequent comparison, only medicines with the identical strength were considered. To adjust to different package sizes, the unit price of one pill was calculated.

(4) The nominal value of a good is its value in terms of money rather than some other good, service, or bundle of goods.

(5) The prevailing model of innovation for new medicines allows the innovator company to recoup hypothetical R&D costs through high prices while being protected against competition by intellectual property rights enforcement. An innovation model based on patent monopolies therefore relies on high prices for the resulting medical technologies.

References

- Leopold, C., Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K., Seyfang, L., Vogler, S., de Joncheere, K., Laing, R.O., and Leufkens, H. (2012). Impact of External Price Referencing on Medicine Prices – A Price Comparison among 14 European Countries. South. Med Rev. 5, 34-41.

- OECD, and European Union (2014). Health at a Glance: Europe 2014 (OECD Publishing).

- Kanavos, P., Vandoros, S., Irwin, R., Nicod, E., and Casson, M. (2011). Differences in Costs of and Access to pharmaceutical products in the EU. Brussels: European Parliament. Policy Dep. Econ. Sci. Policy.

- Carone, G., Schwierz, C., and Xavier, A. (2012). Cost-containment policies in public pharmaceutical spending in the EU.

- WHO Hepatitis C, Fact sheet N°164, Updated July 2015.

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Hepatitis C.

- European Medicine Agency, European public assessment report (EPAR) for Sovaldi, last updated on 20/07/2015.

- Light, D. and Lexchin, J. (2012). Pharmaceutical research and development: what do we get for all that money? British Medical Journal (BMJ). 345.

- Adams, B. (2013). GSK chief: drug prices should be lower. PharmaTimes Online.

- Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Annex IC to the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation, signed in Marrakesh, Morocco, on April 15, 1994, (TRIPS), Articles 28.1 a and b.