Main content

Part 2 – Challenges & Progress Made

Diagnostics

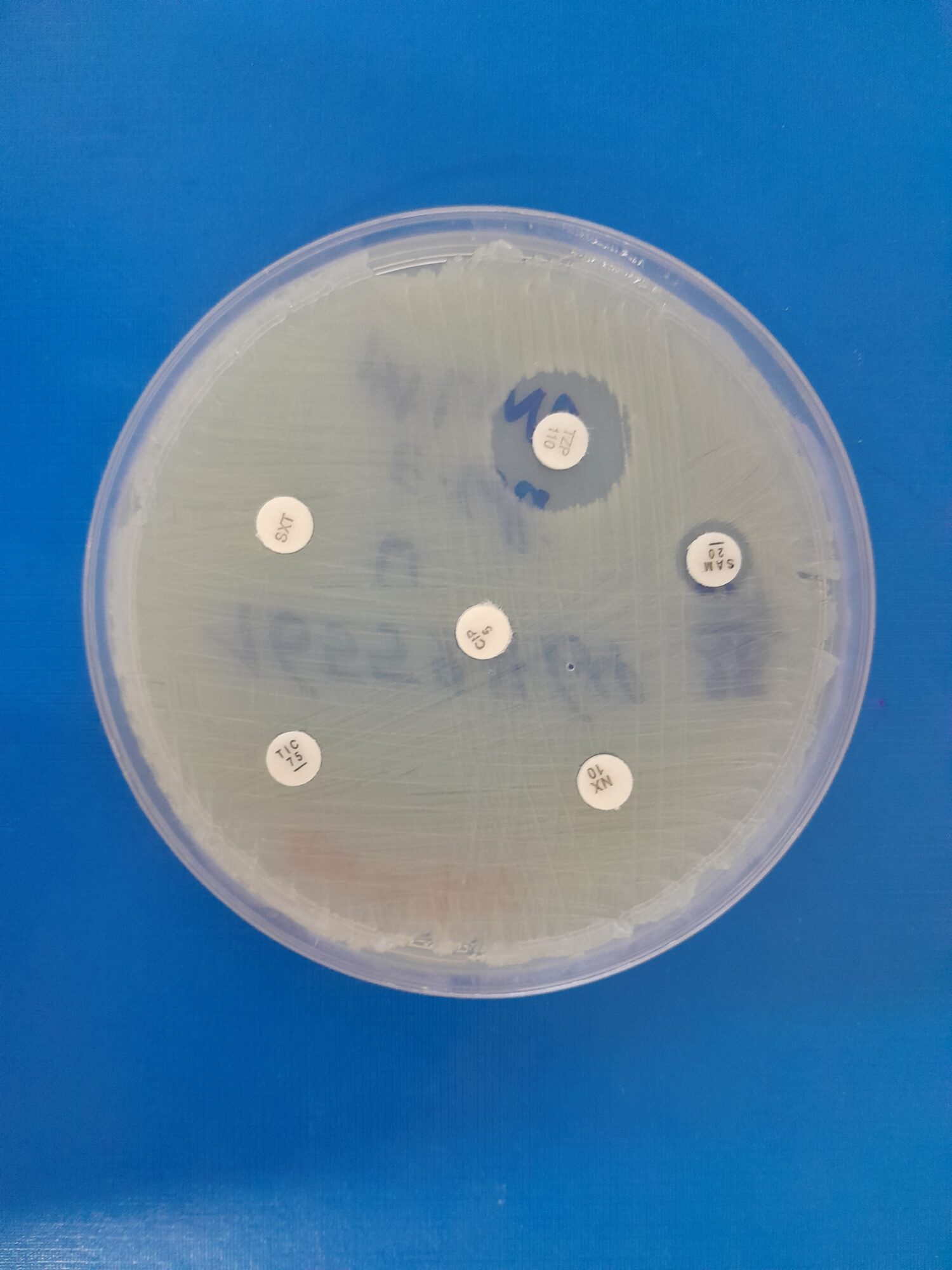

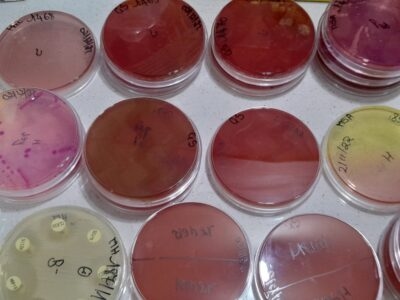

Detecting antimicrobial resistance requires reliable diagnostics. I am fortunate to work in a tertiary hospital where we can consistently identify the most common bacteria such as Staphylococci, E. coli and Klebsiella through culture, without frequent diagnostic stockouts. However, identifying fastidious or intracellular bacteria, certain fungi, and many viruses remains difficult or even impossible using standard laboratory methods. Molecular testing is expensive and limited to specific conditions. Infectious diseases are still a daily burden of disease, yet many healthcare facilities in the region – and in many parts of Sub-Saharan Africa – do not have routine infection markers or basic chemistry tests available, let alone microbiology services. In regions where microbiology services do exist, samples are frequently sent to external laboratories, leading to delayed or incomplete results that may not answer clinicians’ questions. As a result, the true burden of antimicrobial resistance in many healthcare settings and communities is unknown, and empiric treatment is the only option. This is problematic, as almost every day we encounter resistance, such as patients who fail to clear malaria parasites despite antimalarial treatment or patients presenting with community-acquired ESBL-producing bacteria in their urine. According to the 2025 Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report from the WHO [1], over 70% of infections with E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the African Region are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, which are commonly used as empiric therapy.

Meanwhile, laboratories are being built, and outbreaks, particularly COVID-19, mpox and viral hemorrhagic fevers, have resulted in an immense boost across the continent in understanding the importance of laboratory testing for infectious diseases. This rapid increase in demand has led both private and public institutions to start molecular testing [2,3]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I witnessed a sudden transformation in Addis Ababa, within a single year, from an almost complete absence of molecular testing to many private and public facilities being able to perform PCR testing.

Diagnostics for antimicrobial resistance have similarly advanced through the adoption of molecular and genomic tools. For example, studies by my colleagues in Rwanda, including Musana Habimana Arsene (AMR Initiative Rwanda, co-author of this article), have applied molecular surveillance of Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 mutations for malaria and whole-genome sequencing for Campylobacter, enabling faster and more accurate detection of resistance. As diagnostic capacity expands, research on antimicrobial resistance and efforts in AMR surveillance have accelerated in sub-Saharan Africa. A recent publication from the East African region illustrates notable progress in the implementation of AMR surveillance interventions [4]. Kenya, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania have established national systems with designated reference laboratories, coordination centers and surveillance sites. However, implementation varies and many gaps remain in laboratory capacity, trained staff, and genomic surveillance, as well as a limited number of surveillance sites. Nevertheless, this represents a major step forward compared with just a few years ago, and marks an essential step toward understanding the burden per nation and per region. For the average person in the village, this progress means that health authorities will be better equipped to identify which antibiotics are still effective, and it can also guide the availability of effective antimicrobials in the community.

From laboratory to the bedside

Yet, simply building laboratories with the capacity to detect microorganisms and antimicrobial resistance is not enough. Uninterrupted supplies, knowledge at all levels, and antimicrobial stewardship are equally important. Clinicians, laboratory personnel, pharmacists, and supporting staff should understand what to do with results coming from a molecular or microbiology laboratory, or should have someone to consult. A change in mindset is also needed. If clinicians are used to prescribing without consultation, why would these prescribers suddenly seek advice from an infectious disease specialist, microbiologist or clinical pharmacist? Without adequate knowledge, access to experts, and interdisciplinary communication, mismanagement can easily happen.

I observe examples of this daily: patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) who remain unnecessarily on vancomycin while there are safer, susceptible options available; Acinetobacter baumannii isolates detected in tracheal aspirates treated indiscriminately, while this could be colonization; bacterial infections assumed to be excluded after only one negative set of blood cultures; azithromycin prescribed for urinary tract infections as it was reported sensitive despite poor urinary concentrations; and bacteria tested by disk diffusion for certain antibiotics while the organisms are known to be intrinsically resistant.

Other examples concern treatment choices: antibiotics that fail to reach therapeutic concentrations in the central nervous system being prescribed for suspected meningitis; all stool samples with white blood cells being treated empirically with antibiotics; treating asymptomatic bacteriuria; and bacteriostatic agents being used in cases of sepsis. Even when laboratories generate a beautiful culture and sensitivity report, appropriate antibiotics may be unavailable. Interrupted supplies of antimicrobials or materials for identification and sensitivity testing can result in multiple treatment changes within a single week or lead to unidentified bacteria and fungi. Additionally, a strong link with infection prevention and control (IPC) is necessary. If diagnostic capacity exists but IPC practices are not implemented in healthcare facilities and communities, AMR will continue to emerge and spread.

The expansion of molecular testing will undoubtedly change the future but also requires caution and expert clinical guidance. A case in point here is a patient with constrictive pericarditis who tested positive for TB on a GeneXpert assay from pericardial tissue, despite having already completed six months of treatment. No culture was sent for confirmation. Without guidance from an infectious diseases specialist who could explain that GeneXpert detects DNA that can remain detectable even after bacteria are dead, this result could have led to another unnecessary six-month course of therapy. Detection of bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites by PCR or sequencing has so many advantages compared to traditional methods, but it needs clinical correlation to determine whether the findings are normal flora, colonization, a previous infection, or a current pathogen.

The examples presented above call for a strong interaction between laboratories and the clinic, but professionals that connect these two fields are still very limited in supply. Despite this, progress is on the way. In many sub-Saharan African countries, training programmes in medical microbiology, infectious diseases, molecular biology, clinical pathology, and clinical pharmacy have begun or are about to start, often with international collaboration. I encounter many of these students in the hospital. Such professionals can help close the gap and link medical microbiology to other One Health components. From my personal experiences in Rwanda and Ethiopia, I have observed that clear guidance from infectious disease physicians, clinical microbiologists, infection prevention and control (IPC) professionals, engaged pharmacists, and laboratory technologists can lead to a substantial shift in mindset within a healthcare facility. Once these professionals become visible and proactive, making meaningful contributions to multidisciplinary meetings and daily consultations, other healthcare providers and patients begin to rely on them for direct guidance, and prescribing practices improve significantly.

Antimicrobial availability

Both lack of access and misuse of antibiotics are major drivers of resistance and a critical barrier to effective antimicrobial stewardship. In most countries on the continent, antimicrobials are still available to the general public without prescription, including the circulation of poor-quality antimicrobials and non-WHO-recommended antibiotics [5]. A 2020 meta-analysis found that in Sub-Saharan Africa, over two-thirds of consultations or direct antibiotic requests at community drug retail outlets resulted in antibiotics being dispensed without a valid prescription [6]. In many villages and towns across sub-Saharan Africa, people routinely purchase common antibiotics like amoxicillin or co-trimoxazole from small local shops or pharmacies without consulting a healthcare professional. Consequently, antimicrobial resistance, especially to these drugs, is increasingly prevalent in the community [7,8].

When individuals who self-medicate with antibiotics require hospital admission, the impact of prior antibiotic use becomes evident: it lowers the culture yield, shapes patient expectations, and influences physicians’ prescribing behaviour. A case in point is a child we had to admit in critical condition with pericarditis and polyarticular septic arthritis, in whom repeated pus samples show no bacterial growth due to prior antibiotic use. Clinicians tend to escalate directly to last-resort antibiotics such as meropenem and vancomycin in such cases. Ass a clinical microbiologist, it is difficult to reassure my colleagues that first-line antibiotics may still be an appropriate choice here.

Rational prescription

Even the involvement of formal prescribers doesn’t ensure rational use. In Ethiopia, I saw many patients receive a cocktail of dexamethasone, ceftriaxone, and diclofenac when they were not feeling well, often prescribed by doctors in private clinics. During COVID-19, patients were frequently admitted in our hospital who had been treated at home with broad-spectrum antibiotics, sometimes even vancomycin or meropenem, prescribed by physicians visiting them at home. The availability of reserve drugs on the market such as caspofungin, ceftazidime-avibactam or polymyxin B is great for the patients who need them, for example, patients in ICU with sepsis caused by candidemia or multidrug resistant bacteria, babies who develop line-sepsis after successful heart surgery, or patients with neutropenic fever. But the availability of these drugs without proper regulations or legislation is creating a new crisis. Colleagues in the region already report patients, especially in intensive care units, whose bacterial resistance extends beyond the WHO’s last-resort ‘reserve’ antibiotics [9], which I also occasionally see.

Pre-admission use of antibiotics, whether from another hospital or through self-medication, is a huge problem that cannot be addressed at the hospital level alone. Tackling this issue requires a One Health approach, initiated by national and regional regulations covering human, animal and environmental health, backed by strong enforcement mechanisms. Rwanda’s National Action Plan (NAP 2.0) on AMR [10], to which I contributed through participation in technical workshops, outlines regulated antimicrobial use, including measures such as prescription-only access to antibiotics. Similar principles are reflected in other national action plans on AMR across sub-Saharan Africa. The critical step now is ensuring effective implementation of the national action plans, supported by transparent monitoring and accountability. Other One Health components, such as antimicrobial use in animals and agriculture, as well as environmental contamination with antimicrobials, must be addressed as well, rather than focusing on the human perspective only. Although data from sub-Saharan Africa are scarce, there is evidence that these sectors contribute to AMR, with high levels of resistance in agriculture and food production and poorly regulated antimicrobial use [11].

Awareness

Awareness of AMR and progress in antimicrobial stewardship are growing across sub-Saharan Africa at multiple levels: through national policies, within healthcare systems, and at the community level. While there is still room for improvement, I have observed a positive change over the past decade. Better diagnostics, training, cross-sector collaboration and new technologies are strengthening stewardship and resistance detection. Molecular diagnostics reduce reliance on empirical treatment, while AI has not left Africa untouched either, strengthening AMR surveillance by analysing large datasets and predicting resistance trends. Many hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa now have antimicrobial stewardship teams. AI-driven decision-support systems are starting to assist antimicrobial stewardship by guiding appropriate antibiotic use based on local resistance patterns.

Young professionals from diverse medical backgrounds are passionate about tackling AMR. An example of this is the AMR Initiative Rwanda, a group of young experts working together to combat AMR through training, research and high-level advocacy. Its founder, Marcel Ishimwe, a pharmacist, started this initiative because he saw the need to create awareness of AMR and to strengthen Rwanda’s One Health approach. Through AMR Initiative Rwanda, young people in communities, schools and universities are empowered and trained on AMR, IPC and antimicrobial stewardship. Ishimwe has observed significant progress in AMR awareness in Rwanda and across Africa during recent years. Governments, academic institutions and civil society integrate antimicrobial stewardship into training programs and develop national action plans on AMR, even though funding is a major issue, especially at present. He has also observed an improvement in access to quality antimicrobials due to stronger procurement and regulations, despite persistent challenges such as inappropriate use and substandard medicines.

Conclusion

Our two articles on provide insights into the background, daily practice, and challenges related to antimicrobial resistance encountered while working in sub-Saharan Africa. The burden of resistance on the continent is substantial and real. It requires a lot of hard work, manpower, resilience and strong regulatory frameworks. Implementing antimicrobial stewardship in healthcare facilities is often frustrating, ranging from patients freely buying antibiotics around the corner to facing extremely resistant bacteria. Fortunately, many improvements have been witnessed over the past years, including increased awareness, stronger stewardship, better diagnostics, improved surveillance, One Health initiatives, and expanded training and education. At the same time, the AMR crisis is evident and urgent, calling for more action: no action today means no cure tomorrow.

Author

M.J. Kreuger

MD Global Health, MSc Medical Microbiology

King Faisal Hospital Rwanda

Contributions by

Marcel Ishimwe

Pharmacist

Founder AMR Initiative Rwanda

Musana Habimana Arsene

Biotechnologist

AMR Initiative Rwanda

References

- WHO. Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025: WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Accessible via: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240116337

- Kebede A, Lanyero B, Beyene B, Mandalia ML, Melese D, Girmachew F et al. Expanding molecular diagnostic capacity for COVID-19 in Ethiopia: operational implications, challenges and lessons learnt. Pan Afr Med J 2021;38:68. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.68.27501

- Jacobs JW, Adkins BD, Milner DA Jr, Bloch EM, Eichbaum Q. Survey of clinical microbiology and infectious disease testing capabilities among institutions in Africa. Am J Clin Pathol. 2025;163(4):526-530.

- Molina A, Ihorimbere T, Nzoyikorera N, Nambozo EJ, Namubiru S, Nabadda S et al. Strategies and challenges in containing antimicrobial resistance in East Africa: a focus on laboratory-based surveillance. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2025;14,134. doi:10.1186/s13756-025-01662-y

- Vliegenthart-Jongbloed K, Jacobs J. Not recommended fixed-dose antibiotic combinations in low- and middle-income countries – the example of Tanzania. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2023;12(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13756-023-01238-8

- Belachew SA, Hall L, Selvey LA. Non-prescription dispensing of antibiotic agents among community drug retail outlets in Sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021;10:13. doi:10.1186/s13756-020-00880-w

- WHO-AFRO. Antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region: A systematic literature review. Brazzaville: World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa; 2021. Accessible via: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2021-11/Antimicrobial%20Resistance%20in%20the%20WHO%20African%20region%20a%20systematic%20literature%20review_0.pdf

- The New Times. What to know as Penicillin, Amoxicillin lose effectiveness in Rwanda. November 26, 2025. https://www.newtimes.co.rw/article/31528/news/health/what-to-know-as-penicillin-amoxicillin-lose-effectiveness-in-rwanda

- WHO. Web Annex C. WHO AWaRe (access, watch, reserve) classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use, 2023. In: The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: Executive summary of the report of the 24th WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 24 – 28 April 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Accessible via: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.04

- Rwanda Biomedical Center. 2025-2029 National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2025. Accessible via: https://rbc.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/strategy/2nd_NATIONAL_ACTION_PLAN_ON_AMR__NAP_2025-2029_.pdf

- Mshana SE, Sindato C, Matee MI, Mboera LEG. Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Agriculture and Food Production Systems in Africa: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;10(8):976. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080976