Main content

How can we structurally improve the health of populations and health systems in countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America? Since 1964 KIT has been doing just that. Via its International Course in Health Development (ICHD), it has been strengthening the expertise and ability of health professionals who work or are going to work in these countries to improve public health there. This course became a full Master of Public Health (MPH) in 1970. In 2005, another Master’s in international health (MIH) was added, building on the already existing NTC, Netherlands Course in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Who participates in the MPH and MIH programmes?

The target group for both Master’s is slightly different. The MIH targets more medically oriented health professionals, working to build a career in international health. Half of the students are Dutch tropical doctors/AIGT who would like to pursue their career in global health; the other half are international students. The course is especially suited for people who cannot leave their homes and jobs fulltime for one year. The programme can be taken part time and partially distance based. For many people who work in low and middle income countries with limited funding, this is the best way to combine work and personal developments in the field of international health.

The MPH/ICHD is geared towards health professionals who have more working experience, at the national, regional or district level in governments, NGOs or educational institutions. They need to have managerial experience and come from a broader variety of educational backgrounds. They have worked in countries ranging from Myanmar to Mexico and from Indonesia to Zambia. The group usually consists of more than 15 nationalities.

Course content

The MPH/ICHD starts with epidemiology and statistics, which serve as a basis to explore the social determinants of health. The course continues with modules in health management, policy and systems, and health planning, in which students in groups develop and present a proposal. In the Qualitative methods for health systems research module, students develop their own research proposal. In the Human resources for health module, students discuss issues such as development, motivation and retention of health personnel. Depending on the track, students deepen their competencies in either “Health systems, policy and management” or “Sexual and reproductive health and rights, including HIV/AIDS” or in “Health Systems in Fragile and Conflict-affected Environments”. The course concludes with a visit to various organisations in Geneva and a thesis, including an oral exam.

The MIH starts with a core course of 3 months, called the NTC, the Netherlands Course in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, in which determinants of health, health problems, basic research methods and health systems are discussed. After that, students can choose a large variety of different modules at various institutions in the tropEd network (www.troped.org), including KIT itself. The course concludes with a thesis. The Master course can be done in 1 year fulltime or 5 years part-time. The Master course allows students to build on their existing competencies and to focus on strengthening competencies that they still miss to do their jobs better and to move on with their career. The programme is thus tailor-made for each student. Content can focus on specific health problems, for example non-communicable diseases, maternal or child health, or nutrition. Also, students can choose to put extra emphasis on specific skills for example those related to research, management, monitoring and evaluation, or policy making.

Comparison with other master’s, internationally

While most MPHs in Europe focus on their own country, KIT’s Master’s focuses specifically on low and middle income countries and their challenges, with a major emphasis on disadvantaged populations, and applying context-specific solutions. Though both Master’s programmes can serve as a stepping stone for an academic career, including a PhD, the emphasis is on application of theory in practice. KIT collaborates with all important similar institutions in Europe and abroad.

| “Studying at KIT helped me to have a critical mind and to really think out of the box. I work now for the National Cancer Prevention Centre in Zambia. We have screened close to 200,000 women in the cervical cancer programme which has never happened before in this country. Though the incidence and mortality rates are still high there has been massive awareness on the disease. We have also managed to have international recognition on the programme and have trained people from 11 other African countries. I could not have succeeded in all that without the training in public health at KIT.” – Sharon Kapambwe from Zambia, MPH, background medical doctor. Currently working as director of National Cancer Prevention Centre “At KIT I was particularly impressed about the course content, the teaching staff composed of world class public health experts and leading academics and researchers, as well as the support staff whose teaching, guidance and administrative support combined to improve my academic orientation and shape my thoughts about public health and its practice.” “The NTC was a perfect preparation for my work as tropical doctor (AIGT). I was trained in both clinical aspects as more public health related issues by KIT facilitators who had a lot of experience and expertise. This helped me enormously during my work in the field. At the same time it was the start of my knowledge, network and career in international health. Later I studied the Master in International Health and am currently working on research on heart and vascular diseases in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya.” |

The Master course in International Health is offered by a number of institutions within the tropEd network. In some institutions of the tropEd network, participants can take a full MIH; other institutions only offer a core MIH course or only advanced modules; see http://www.tropEd.org/institutions/. The KIT MIH has the same requirements for graduation as other tropEd institutions, and the courses are structured in a similar way with a core course, a number of advanced modules, and a thesis. This was made possible by a strong peer accreditation, with common standards [1]. Both programmes are accredited by national and international bodies, such as Dutch-Flemish Accreditation Organisation (NVAO) and tropEd, and have good scores on quality.

Master programmes proof career changing

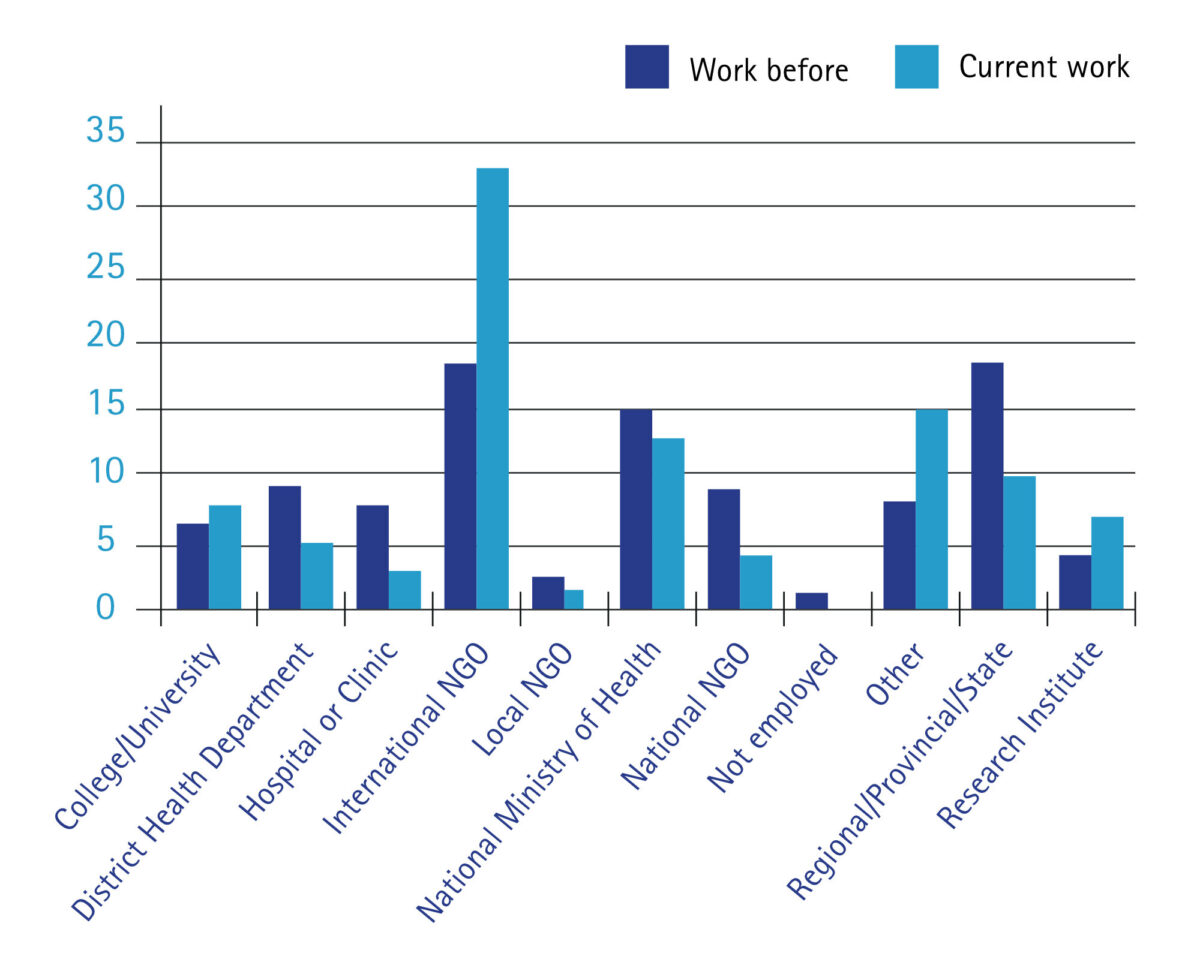

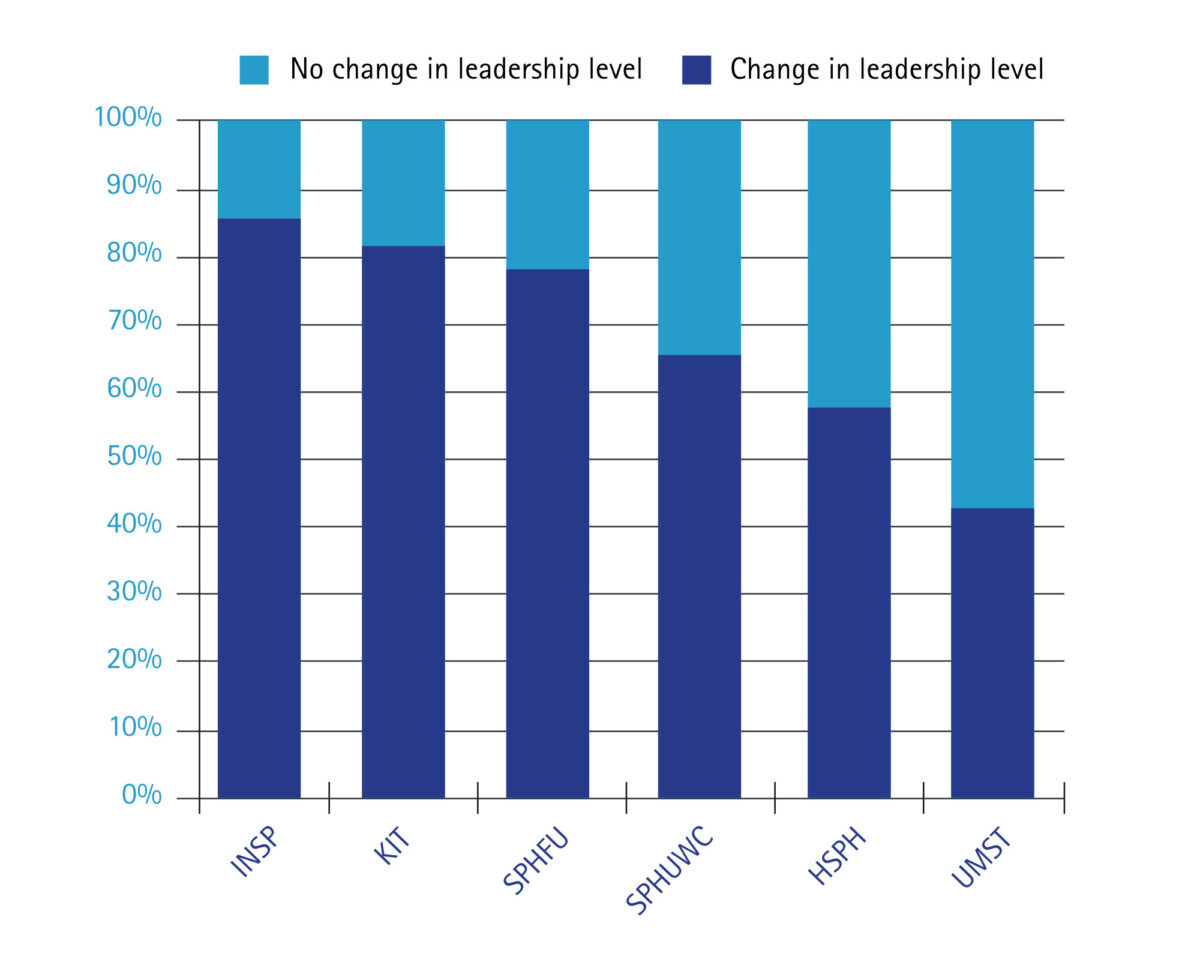

KIT keeps track of its alumni via alumni surveys and personal contacts. As for the MPH/ICHD, an alumni survey carried out in 2013 showed that, prior to enrolling in the course, most alumni worked for a regional/ provincial or state health department or international NGO or at the national Ministry of Health (18%, 18% and 15% respectively). After graduation, the distribution shifted towards an international NGO, a research institute, or some other institute (33%, 15%, 7% respectively) (see figure 1). Unlike some other training programs, almost all graduates return to their home countries, where they try to make a difference; the quotes below illustrate this. Some started working for international organisations in their own or neighbouring countries. KIT graduates showed high rates of improvement in leadership level (80%) in comparison with MPH programmes in other countries; see figure 2 [2,3]. Graduates stated that the MPH programme had equipped them with important competencies, such as public health science skills, including analytical assessment (74%), context sensitive competencies (76%) and planning and management competencies (67%).

Surveys among MIH graduates showed that many of them had moved to a new position in their organisation or in the health system; see figure 2. They tend to work more often at the national or international level. After completing the MIH programme, many respondents became active in training/education and/or research. A tropEd-wide alumni survey in 2010 showed similar results [4]. Respondents were asked what they considered the three most important contributions to their current work that they could attribute to the MIH programme. They mentioned improved research skills (54.5%), improved critical analysis/analytical skill (36.4%), and improved knowledge on the field of interest (36.4%). They also mentioned an impact on their networking and writing skills (27.3%). As strengths of the MIH programme, the alumni mentioned the diversity in both background/experience and culture among their peers and the opportunity of networking. The quality of the teachers and their flexibility were also highly appreciated.

*Missing: 26

Impact on health systems

Quantitative and qualitative studies have shown that alumni make a difference at their workplace and in the health systems where they work. The graduates themselves, their peers, and their supervisors reported positive changes at the workplace level, especially in terms of management, leadership, innovation, teaching and training, advocacy, community engagement and research involvement. Effects mentioned outside of their immediate workplace included an inter-sectoral approach, a national footprint via policy advisory roles for Ministries of Health, policy development, and capacity building [2, 5].

The future

The KIT Master programmes can look forward to a healthy future. In conjunction with two other European institutions, project modules and e-learning tracks are being developed via an Erasmus Plus project, so as to respond to the growing demand for courses. Other e-learning modules will also be developed, building on KIT’s strengths: small-scale, highly interactive, flexible learning, coupled with substantive field knowledge. It will soon be possible for students to follow the ICHD/MPH part-time. By developing its own fellowship fund, KIT hopes to help and invest in committed students from low-income countries and to strengthen their skills; please see www.kit.nl/fellowships. In view of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and its associated goals and international targets, Master programmes in international health and public health will remain relevant for a long time to come.

References

- Zwanikken P, Peterhans B, Dardis L, Scherpbier A: Quality assurance in transnational higher education: a case study of the tropEd network; BMC Medical Education 2013, 13:43 doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-43

- Zwanikken PA, Huong NT, Ying XA, et al: Outcome and impact of Master of Public Health programs across six countries: education for change. Human Resources for Health, 2014, 12:40, DOI: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-40

- Zwanikken PA, Alexander L, Huong NT, et al: Validation of Public Health Competencies and Impact Variables for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. BMC Public Health, 2014;14:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-55

- Gerstel L, Zwanikken PAC, Hoffman A, et al: Fifteen years of the tropEd Masters in International Health programme: what has it delivered? Results of an alumni survey of masters students in international health. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2013, doi:10.1111/tmi.12050

- Zwanikken PAC, Alexander L. Scherpbier A: Impact of MPH programs: contributing to health system strengthening in low- and middle-income countries? Human Resources for Health 2016 14:52 DOI: 10.1186/S12960-016-0150-7