Main content

Project reports from the global health residency programme

| The 27-month AIGT (medical doctor in global health and tropical medicine) training programme, offered by the OIGT training institute in the Netherlands with support from the Netherlands Society for Tropical Medicine & International Health (NVTG), is concluded by a Global Health Residency of six months duration in a low-resource setting. Residents undertake two projects aimed at tackling locally relevant public health problems. Attaining knowledge of the social determinants of health as well as the epidemiology and burden of particular diseases and finding out how local health systems address these are some of the learning objectives. Since the introduction of the training programme in 2014, a large variety of public health research projects have been completed. In this new section, MTb offers a platform for AIGT trainees to present the findings of their projects. |

Setting

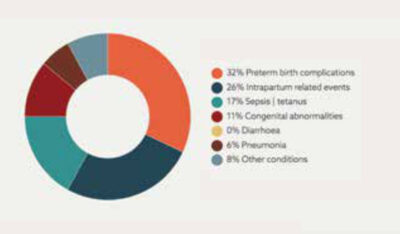

Nkhoma Mission Hospital is a 104-year old district hospital in the southern region of Malawi, with 250 beds serving a catchment area of 460,000 people. Annually, an average number of 13,000 patients are admitted and approximately 46,000 outpatient cases seen. In 2016, Nkhoma Mission Hospital opened its own nursery, which received over 800 admissions in 2018. Primary reasons for admission were prematurity, low birth weight, birth asphyxia, neonatal sepsis and congenital abnormalities. [1]

Background and rationale

It is estimated that annually a staggering 2.7 million neonatal deaths and 2.6 million stillbirths occur globally, of which the majority are preventable. To address this, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the global Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP) in 2014. [2]

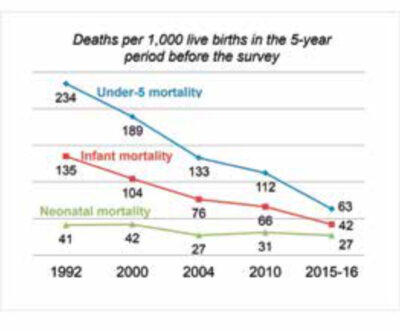

Malawi successfully achieved millennium development goal 4, ahead of the 2015 deadline. However, as shown in Figure 1, most of the progress made has been due to a reduction in infant and under-5 mortality, as opposed to neonatal mortality. [3] Additionally, although the neonatal mortality rate (NMR) has indeed declined by about 2% per year since 2007, absolute numbers remain high, with a NMR of 23/1,000 live births in 2017. [4] In comparison, the global average NMR was 18/1,000 live births in 2017, and 2/1,000 in high-resource settings. [5,6]

The high NMR in Malawi persists despite an increase in the rate of deliveries in health institutions from 53% in 2000 to 90% in 2014, suggesting that neonatal mortality is not solely related to the location of delivery but – perhaps more importantly – to the quality of care provided in these facilities. [7]

In 2015, in response to the global ENAP, the government of Malawi developed its own Newborn Action Plan aimed at reducing the NMR to 15/1000 live births by 2035. [8] Crucial in this plan is the implementation of neonatal death and stillbirth audits in every health facility across the country. [8]

Although initial trainings had already been delivered and the necessary data management and surveillance systems implemented, neonatal death audits were not routinely conducted at Nkhoma Mission Hospital before September 2019. Therefore, at the request of, and in collaboration with, the hospital’s management team, clinical officers and nursing staff, an initiative was undertaken to introduce these audits.

Aim

The aim of the Global Health Residency project was to reduce neonatal mortality in Nkhoma through the collection of neonatal death data and the introduction of a monthly audit.

Methods

The neonatal death audit was organized on a monthly basis by the resident GHTM medical doctor, in collaboration with the responsible clinician of the nursery. Clinical staff from various departments also took part. During each meeting, an overview of the preceding months’ mortality was presented and one case was audited using the national forms as a guideline. Modifiable factors were identified and possible solutions proposed with actionable tasks being delegated to team members.

Results

Monthly neonatal death audits have been conducted in Nkhoma Mission Hospital since they were introduced in October 2019. The audit meetings led to the identification of various modifiable factors, of which the most important ones are described in Table 1. Solutions that were proposed and implemented included:

- introduction of an agreement on 4-hourly vital signs monitoring in all neonates in the nursery with documentation in specific charts

| MODIFIABLE FACTOR |

|---|

| Poor monitoring of vital signs |

| Absence of ward rounds during weekend |

| Inadequate record-keeping in the ward |

| Essential medication not administered |

| Insufficient monitoring of feeds in critically ill neonates (e.g. very low birth weight babies, babies on ventilation support) |

| Insufficient (written) handover of babies admitted and transferred from labour ward to nursery ward |

- guarantee of continuity of care during weekends and public holidays through daily ward rounds by the paediatric clinician on duty

- appointment of one nurse as team leader of the maternity ward during night shifts, who is responsible for critically-ill pregnant women and timely administration of prescribed drugs (for example nifedipine and dexamethasone)

- monitoring of feeding of premature babies through the use of feeding charts for every baby born with a birth weight of 1,500 grams or less

- optimal handover of neonates from the labour ward through optimizing completion of admission sheets with clinical details around delivery.

The impact of the audits and subsequent interventions can be evaluated via the NMR. In September 2019, the NMR in Nkhoma was 30/1,000 live births (271 babies born alive, 8 neonatal deaths). Of the eight neonatal deaths, four were due to birth asphyxia, three due to prematurity/low birth weight, and one due to neonatal sepsis. In October 2019, the NMR had shown an encouraging drop to 16/1,000 live births (315 babies born alive, 5 neonatal deaths). Of the five neonatal deaths, one was due to birth asphyxia and four due to prematurity/low birth weight. For comparison of NMRS before and after audits, see Table 2.

| TOTAL LIVE BIRTHS | TOTAL NND | NMR PER 1000 LIVE BIRTHS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| JANUARY | 270 | 9 | 33 |

| FEBRUARY | 276 | 16 | 58 |

| MARCH | 212 | 6 | 28 |

| APRIL | 278 | 2 | 7 |

| MAY | 310 | 11 | 35 |

| JUNE | 264 | 6 | 23 |

| JULY | 316 | 13 | 41 |

| AUGUST | 310 | 8 | 26 |

| SEPTEMBER | 271 | 8 | 30 |

| OCTOBER | 315 | 5 | 16 |

Discussion

Neonatal death audits were successfully introduced at Nkhoma Mission Hospital in October 2019, with staff routinely filling in death audit forms and action plans being formulated and implemented. An encouraging drop in NMR has been observed since, but future data need to confirm this trend. A clear pattern in the most important causes of death and related modifiable factors has been identified. Insufficient monitoring of neonates by nursing staff and clinicians, inadequate response to emergency signs, and suboptimal record keeping were identified as areas of concern.

Based on the above, multiple interventions were initiated, of which several have been successfully implemented. In order for the audits to remain effective and prove sustainable, the following challenges need to be overcome:

- enhancing ownership of the audits by local staff

- motivating the staff of the wards outside of the nursery to attend the audits in order to achieve multi-disciplinary and widely supported solutions

- creating an open and respectful audit culture which prevents naming and shaming and invites participants to speak and contribute

- ensuring adequate follow-up of implementation and continuation of proposed solutions

Conclusion

The smooth and well-accepted introduction of neonatal death audits, the enthusiasm and involvement of local staff, and the initial reduction observed in neonatal deaths are promising signs for audit continuation and improved management of neonates at Nkhoma Mission Hospital.

References

- Nkhoma Mission Hospital. Nkhoma Mission Hospital annual report 2018. Nkhoma: Nkhoma Mission Hospital; 2019.

- World Health Organization. Making very Baby Count: Audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. p.136 Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/stillbirth-neonatal-death-review/en/.

- National Statistical Office. Malawi demographic and health survey 2015-16. Zomba and Rockville: National Statistical Office and ICF; 2017 February. p.658. Final report. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf.

- UNICEF. Maternal and newborn health disparities: Malawi country profile report. UNICEF Data; 2016 November. p.108. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/country_profiles/Malawi/country%20profile_MWI.pdf.

- UNICEF. Neonatal mortality. UNICEF Data; 2019 September. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/neonatal-mortality/.

- UNICEF, World Health Organization, World Bank Group, United Nations. Child mortality report: levels and trends in child mortality. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) 2018; 2019 September. 48 p. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/47626/file/UN-IGME-Child-Mortality-Report-2018.pdf.

- Leslie HH, Fink G, Nsona H, et al. Obstetric facility quality and newborn mortality in Malawi: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016 Oct;13(10). DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002151.

- Government of Malawi. Every Newborn Action Plan: an action plan to end preventable neonatal deaths in Malawi. Malawi: World Health Organization; 2015. 38 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/pmnch/media/events/2015/malawi_enap.pdf.

- Healthy Newborn Network. Leading causes on neonatal deaths in Malawi (2017). Malawi: Safe the Children Federation; 2017. Available from: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/country/malawi/.