Main content

Elimination strategy of cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is globally the fourth leading cause of death among women.[1] Worldwide, in 2020, there were an estimated 604,127 new cases and 341,831 deaths, mainly among poorer women in society.[2] An infection with high-risk human papilloma virus (hrHPV) can cause precancerous lesions of the cervix. Generally, the immune system can clear the virus. If not, the precancerous lesions can over time develop into cervical cancer. Before hrHPV was identified as the cause of precancerous lesions, cytology (Pap smear) was used to classify the risks of developing cancer. In many Western countries, the Pap smear is still used as the primary screening tool. Low-risk HPV causes genital warts. HPV infection of the cervix is a sexually transmitted disease, which can effectively be prevented by HPV vaccination.

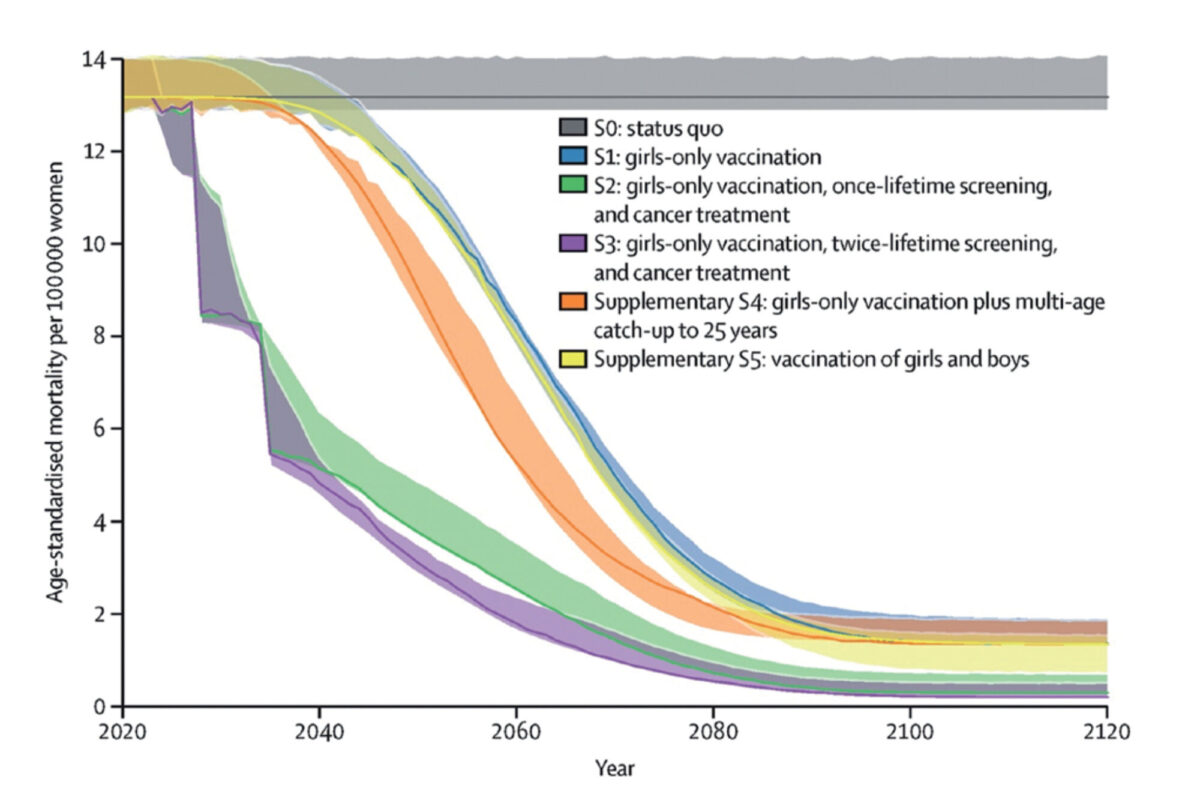

In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem. The strategy includes the following global targets: 1) 90% of girls have received full doses of HPV vaccination by age 15 years, 2) 70% of women are screened at least twice in their life with a high-performance test, and 3) 90% of women identified with (pre)cancer receive adequate treatment.[3] This combination of HPV vaccination, cervical cancer screening, and treatment will fully achieve the cervical cancer elimination targets in the next century and can already reduce mortality by half in 2040 (figure 1).[4]

At the moment, HPV vaccination campaigns have not yet been introduced or widely implemented in low- and middle-income (LMICs) countries, and in the absence of HPV vaccination, millions of women are at risk of cervical cancer.[5] This means that accessible and affordable screening programmes are crucial to early detection of hrHPV and treatment of precancerous lesions.

Innovation in screening for cervical cancer

The WHO guidelines for cervical cancer prevention recommend hrHPV testing of vaginal fluid as the primary screening test. HrHPV positive women are offered either direct treatment with thermal ablation or cryotherapy of the cervix in a screen-and-treat approach, or a second triage test is applied whereby women are treated when precancerous lesions are identified.[6] However, up to now, visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is the most commonly used screening method in LMICS, and only a limited number of LMICs are implementing hrHPV testing. The costs of high-quality PCR testing are generally high (around US$ 50 per test), and the technology of testing is too advanced for clinics in remote areas. The laboratory procedure is comparable to TB testing, often using the same equipment. VIA is cheap and relatively easy to establish. However, both the sensitivity and specificity of VIA are variable and dependent on the skills of healthcare providers performing VIA. The inter- and intra-observational variations result in variation in the quality of screening services, particularly in resource-poor settings.[7] HrHPV testing offers higher sensitivity compared to VIA and cytology.[8] Self-sampling of vaginal fluids for hrHPV testing has the potential to further increase uptake of cervical cancer screening by reducing socioeconomic, cultural, and logistical barriers to participation in screening.[9] Innovative financing models for HPV testing, including self-sampling, are needed to allow accessibility for all women.[10]

Testing feasibility of the who strategy

While the WHO strategy targets both high- and low- and middle-income countries, most research concerning the elimination of cervical cancer comes from high-income countries. HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening are mentioned more and more in national health strategy plans in LMICs in the context of universal health coverage, but actual implementation is challenging.

The PREvention and SCReening Innovation Project Toward Elimination of Cervical Cancer (PRESCRIP-TEC) project studies the feasibility of the WHO strategy in LMICs (Bangladesh, India and Uganda) and vulnerable populations, like ethnic minorities, in Europe (Slovak Republic). These countries have screening and treatment strategies in place but have not yet implemented HPV testing as a primary screening strategy.

Preliminary results of a baseline study conducted among women and decision-makers in the family (e.g. husbands, mothers in law) in these countries showed considerable variation in awareness of cervical cancer, its symptoms and risk factors. Intensive community mobilisation was therefore initiated to convince women and their family members to participate in HPV self-testing (either at home or in a healthcare facility), using not only classical methods of posters and radio messages, but also new approaches like social media. Home-based distribution of HPV self-tests, with personal information from community workers, helped in all countries to achieve an uptake of 80% to 95% among eligible women. Tests were analysed in laboratories in nearby health facilities, and results were then communicated to women, often by text message (if negative) or by community volunteer (if positive).

Preliminary results of our study show substantial differences in prevalence of hrHPV infection between countries and populations. In rural areas in India and Bangladesh, prevalence ranges between 2% and 3% in rural areas and between 6% and 8% in urban areas. In India, HIV-positive women and sex workers are included in the target population, with their hrHPV prevalence being around 30% and 40% respectively. In the Roma population in Slovakia, hrHPV prevalence is between 10% and 12%, and in rural areas in Uganda, around 21%. HIV and HPV multimorbidity is a frequent phenomenon, and therefore all HIV-positive women in Uganda are tested for HPV infection as part of HIV treatment.[11]

Women with an hrHPV positive test result were invited for gynaecological examination in a nearby clinic. When hrHPV testing is done as primary screening, the number of women who need VIA is dramatically lower than when VIA is used as primary screening, since hrHPV-negative women do not need gynaecological examination. This saves much time for women and health workers and saves costs.

Unfortunately, as long as no instant Point of Care (POC) hrHPV test exists, women must wait until the laboratory results are known before travelling to the nearby clinic for follow-up examination. Waiting creates a risk for drop-out of participants, which we try to address by personal support by community volunteers. Drop-out in our project is less than 10% at the moment, while others report higher drop-out rates.[12]

When health workers conduct VIA in the clinics in the PRECRIP-TEC project in Bangladesh, India, and Uganda, they use an Artificial Intelligence Decisions Support System (AI-DSS), which was developed by the Manipal Academy of Higher Education, School of Information Sciences, India.[13] The AI-DSS was developed to reduce intra- and inter-observer variation of the VIA assessment and to allow for task shifting of VIA screening in the future.[14] It is one of the first AI-DSS systems that can be used offline in remote clinics and is built into a smartphone. The first experiences in the project are that the AI-DSS is very user-friendly, but it is too early to conclude that it can replace a health worker’s VIA assessment. A qualified nurse is still needed to recognise full-blown cancers, cervical infections, or other conditions that are not precancerous lesions.

By the end of the project in 2024, we will review the coverage and uptake of the adjusted WHO screening strategy and analyse the cost-effectiveness of the new approach. From our first preliminary data analysis, we can conclude that it is important that cheaper point-of-care tests for hrHPV become available, for example using photonics (lab on a chip) for urine testing. Such tests are expected within 5 to 10 years and have the potential to revolutionise cervical cancer screening worldwide.[15]

International coordination of research

The Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases coordinates five big multi-country research projects into strategies of cervical cancer screening in LMICs, including the PRESCRIP-TEC project. These projects provide new evidence regarding HPV self-testing, community mobilisation strategies, and screen-and-treat approaches. In the coming years, there will be much more knowledge available regarding strategies to increase uptake, the use of artificial intelligence, and the cost-effectiveness and budget impact of potential screening policies in the LMICs in line with the WHO’s elimination strategy. Most LMICs intend to start or scale-up HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening programmes, and scientific evidence will help make this a reality. In short, reducing global cervical cancer prevalence by half in 2040 may become feasible.

| The PRESCRIP-TEC research project is a collaboration between UMCG, LUMC, Female Cancer Foundation, and universities and NGOs in Bangladesh, India, Uganda and the Slovak Republic. It is funded by the European Union and the Indian Ministry of Science and Technology, and coordinated by the Global Alliance of Chronic Diseases. Sultanov M, Zeeuw J, Koot J, et al. Investigating feasibility of 2021 WHO protocol for cervical cancer screening in underscreened populations: PREvention and SCReening Innovation Project Toward Elimination of Cervical Cancer (PRESCRIP-TEC). BMC Public Health. 2022 Jul 15;22(1):1356. |

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71(3):209-249.

- Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health. 2022 Dec 14:S2214-109X(22)00501-0.

- Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M, et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020 Feb 22;395(10224):591-603.

- Brisson M, Kim JJ, Canfell K, et al. Impact of HPV vaccination and cervical screening on cervical cancer elimination: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020 Feb 22;395(10224):575-590.

- Bonjour M, Charvat H, Franco EL, et al. Global estimates of expected and preventable cervical cancers among girls born between 2005 and 2014: a birth cohort analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2021 Jul;6(7):e510-e521.

- WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention, second edition. [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824

- Catarino R, Petignat P, Dongui G, et al. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries at a crossroad: Emerging technologies and policy choices. World J Clin Oncol. 2015 Dec 10;6(6):281-90.

- Mustafa RA, Santesso N, Khatib R, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the accuracy of HPV tests, visual inspection with acetic acid, cytology, and colposcopy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Mar;132(3):259-65.

- Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, de Vuyst H, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019 May 14;4(3):e001351.

- Krivacsy S, Bayingana A, Binagwaho A. Affordable human papillomavirus screening needed to eradicate cervical cancer for all. Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Dec;7(12):e1605-e1606.

- Nakisige C, Adams SV, Namirembe C, et al. Multiple High-Risk HPV Types Contribute to Cervical Dysplasia in Ugandan Women Living With HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022 Jul 1;90(3):333-342.

- Joseph NT, Namuli A, Kakuhikire B, et al. Implementing community-based human papillomavirus self-sampling with SMS text follow-up for cervical cancer screening in rural, southwestern Uganda. J Glob Health 2021;11:04036.

- Kudva V, Prasad K, Guruvare S. Andriod Device-Based Cervical Cancer Screening for Resource-Poor Settings. J Digit Imaging. 2018 Oct;31(5):646-654.

- Hou Xin, Shen Guangyang, Zhou Liqiang, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Cervical Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, Frontiers in Oncology, 12 022

- Gong J, Zhang G, Wang W, et al. A simple and rapid diagnostic method for 13 types of high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) detection using CRISPR-Cas12a technology. Sci Rep. 2021 Jun 17;11(1):12800.