Main content

Historical perspective

Dermatology was often considered a medical specialty that, by inspection alone, deduced and diagnosed the mechanisms that occurred under the skin. It did not use fancy equipment, maybe just a magnifying glass. For teaching and follow-up there used to be watercolour drawings (‘aquarelles’) (Figure 1) and wax mouldings of common conditions, and later analogue photography, which became more useful for the dermatologist when colour photography was introduced. At this stage, a consultation could be as simple as sending photos or negatives by post.

The neglect of patients with skin diseases

Like neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), dermatology seemed like a neglected medical specialty, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Skin diseases account for approximately a third of the burden of disease in LMICS (in high-income countries only fifteen percent), and they are among the top five causes of morbidity. They are responsible for at least fifteen percent of all peripheral health care clinic visits.[1] About ninety percent of the patients with dermatological conditions are seen by primary health care workers or traditional healers with little or no dermatological training, while for more than eighty percent of the patients hardly any specialised knowledge for diagnosis is needed.[1] Most skin diseases are preventable and curable with simple, inexpensive, and effective medications, but must be diagnosed for proper treatment and care. And here help is needed.

The few dermatology specialists present in LMICs almost all resided in the urban areas with little or no contact with rural communities or underprivileged people in slums. As a result, health workers working in these areas were left alone with their patients’ skin problems. Occasionally, they were visited by leprosy health workers from the leprosy/ tuberculosis programme, who knew more about the skin, but who were still not likely to be familiar with other dermatological conditions. Moreover, funding for leprosy became limited since the World Health Organization (WHO) stated in 2005 that leprosy was no longer a public health problem. Later, primary health care workers in general were likely to know more about more acute and highly prevalent illnesses like HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis that would have been a larger aspect of their training. Only recently has interest in dermatology increased as donors and the WHO have put more focus on NTDs with dermatological symptoms, the so-called skin NTDs.

New developments – focus on teaching

Alternative strategies were developed through combining efforts. By the 1980s, Zimbabwe and other countries showed the positive effect of combining leprosy control clinics with general skin health care. It was the first country to control endemic leprosy with multiple drug treatment (MDT), good follow-up, and early detection of infected people. At the same time, the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS) established a training centre – the Regional Dermatology Training Centre (RDTC) for ‘community dermatologists’ – in Moshi, Tanzania: a two-year in-service training in general dermatology, which trained health officers and senior nurses who worked on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and leprosy care. To date, 240 senior clinical officers from thirteen different countries have been trained who provide most of the dermatological care in Zambia, Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Eswatini, Lesotho and Malawi. In other LMICs, similar training centres were established, usually with a shorter training period. However, these professionals with limited training needed the option of consultations with fully trained dermatologists, which were done by post and enclosed photographs.

Teledermatology goes on line

When the internet became available, photos could be sent by e-mail. This greatly speeded up consultations, which were previously done by post, and greatly improved efficiency. This made teledermatology much more feasible and efficient. This great opportunity for low-resource settings was dramatically improved when affordable digital cameras became available that could take excellent pictures. Nowadays, many people have a smartphone, and internet coverage is continuously improving in rural areas, making direct contact between the community dermatologist/ primary health care worker and the dermatology specialist in a town possible. Fortunately, this is changing as more dermatologists are being trained in LMICs or intend to work there.

Clearly, teledermatology helps in making a likely diagnosis with advice for treatment. This increasingly benefits patients who no longer need to travel to see a dermatology specialist, saving them time and money. It is of benefit for the primary health care worker who learns from the consultation by telemedicine, and equally for the dermatology specialist who may earn an income in town and still serve his country. This approach has proven successful, but its sustainability depends on motivated and experienced dermatology specialists who are willing to participate. Teledermatology forums (a panel of dermatology specialists where the one who has time answers first, after which the others add to the discussion) appear to be a possible solution, and some are already operational. For the Dutch reader, the best known example is organised by TROIE: dermatoloog@troie.nl. Over time, telemedicine coverage may increase as more primary health care workers, including community dermatologists, experience the benefit of this service.

Smart applications for skin health

The use of smartphones and digital health technologies is becoming common practice. Applications for dermatology in the field have become increasingly available. However, most technologies are based on the dermatology of the light skin in HICs. The recently launched mobile Netherlands Leprosy Relief (NLR) SkinApp, for example, could be a great support in identifying common NTD- and HIV-related skin diseases, including presentation in the dark skin at the peripheral health care level.[2] The NLR SkinApp can be used during the patient consultation as a source of information about signs and symptoms as well as about the therapy of common skin diseases. It contains pictures to be compared with the lesions of the patient or with pictures taken and stored on the mobile phone. It runs an algorithm that recognises signs and symptoms on the affected body parts and provides peripheral health workers knowledge on less common skin diseases by offering an easy-to-use database of skin diseases as a training tool, including signs and symptoms, pictures, and treatment options. This application can be consulted even in offline settings. While usage is still limited, the ILDS is actively promoting this tool. It is continually under review to improve its performance. It does not completely replace books focused on the common skin diseases in the area. Face-to-face supervision remains necessary, and algorithms need validation, including in HICs.

Other new developments coming into use in remote areas

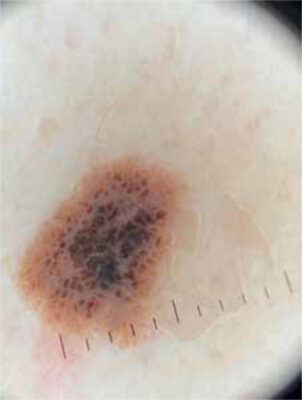

The traditional magnifying glass is becoming more commonly accompanied by the dermatoscope. Dermatoscopy is the examination of skin lesions by means of the dermatoscope (Figure 3). It is also known as dermoscopy or epiluminescence microscopy. It enables inspection of skin lesions to better interpret what is underneath the epidermis (Figure 4). The dermatoscope consists of a focusable magnifying lens, a light source (LED illumination), a flat transparent plate that is in contact with the skin, and sometimes a liquid medium between the instrument and the skin. The new dermatoscopes can digitise the information obtained and send it to experts by mobile phone. Algorithms have been developed to interpret those pictures but are not quite reliable yet and are mostly focused on diagnosing melanoma. For dark skin, extra expertise is needed. This will become available as the dermatoscope is now present in most dermatology training centres in LMICs. For the diagnosis of scabies, it has proven to be extremely handy. Point-of-care tests in dermatology at ground level overlap with those available for NTDs and STDs; a discussion of this is beyond the scope of this paper. Treatment options that are well established in HICs are becoming increasingly available in LMICs, including laser therapy, treatment with UV light (A and B), and radiotherapy, but are not yet available in rural areas. However, the cryogun is now increasingly replacing the liquid nitrogen containing cottonwool swab for cryotherapy of skin malignancies, especially in people suffering from albinism or xeroderma pigmentosum (Figure 5). Common warts and condyloma acuminata can also be treated in this way, even in immunocompromised people. Newer, innovative treatments, for example with biologicals, are beyond the capacity of LMICs and first need research on their safety and efficacy.

Conclusion

The care of skin diseases in LMICs is slowly improving thanks to an increasing number of community dermatologists and the use of new technologies such as the smartphone that facilitate teledermatology, including clinical images and the use of digitised images from the dermatoscope. The introduction of (new) treatment options that are well established in HICs is slow. While some of these tools have been introduced in LMICs some years ago, a systematic evaluation of their impact on patient management in rural areas is eagerly awaited.

References

- Naafs B, Masenga J, van der Werf TS. The Skin. In: Mabey D, Gill G, Parry E, et al, editors. Principles of Medicine in Africa. 4th edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013, p. 928 (779-810)

- NLR International [Internet]. Amsterdam: NLR. SkinApp. Available from: https://nlrinternational.org/what-we-do/projects/skinapp/