Main content

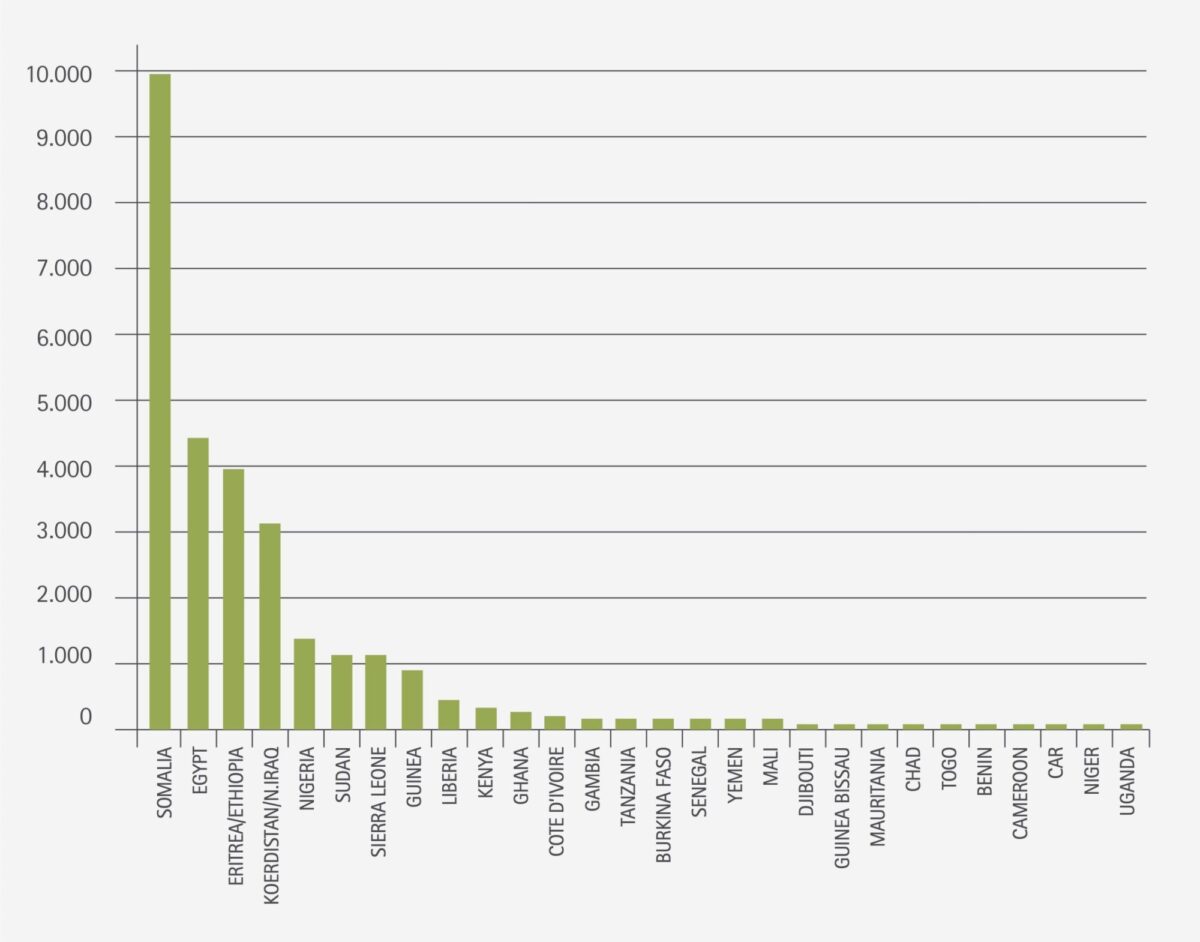

More than 125 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to FGM in the many countries in Africa, the Middle East and South East where FGM is performed. As many as 30 million girls are at risk of being cut over the next decade if current trends persist [1].

Migration resulted in the prevalence of FGM in Europe. There are an estimated 29,120 women with FGM living in the Netherlands. The majority of these women fall within the reproductive ages. This requires skills from doctors and other health care workers to discuss this topic, proper knowledge of the relation between medical and psychosocial complaints related to FGM, as well as knowledge of existing medical treatments or therapies [2].

Classification [3]

Type I

Clitoridectomy – Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce.

Type II

Excision – Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora.

Type III

Infibulation – Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris.

Type IV

All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.

Long term consequences

It is increasingly recognized that FGM causes complications throughout the life span, divided into three main areas: gynaecological, obstetric and psychological (including sexual function).

Gynaecological

A systematic review examined infection rates in 22,052 African women with FGM of all main types [4]. Types of infections identified included urinary tract infections, genitourinary tract infections, abscess formation, septicaemia and HIV. Infections were more frequent in women who had undergone type III. Although the study did not include a control group, the fact that more severe forms of FGM correlated with higher frequency of infections, suggested that FGM is a risk factor for infections. Painful and unsightly scarring due to keloid has been reported. Also cysts can obstruct the vagina and cause pain. They can be very large and may require surgical excision. It is possible that a very narrow vaginal opening might slow down menstrual flow, while damage to the urethra during FGM may lead to fistula and urethral strictures [5].

Obstetric

A study of 28,000 women with FGM across 6 African countries as well as a large systematic review involving almost 3 million participants from USA and Europe showed that women who have undergone FGM suffer more frequently from prolonged, difficult labour, have a higher rate of obstetric lacerations, more often require instrumental delivery, and have increased rates of obstetric haemorrhage. This may be due, in part, to the inelasticity of scar tissue [6-7].

Miscommunication, distrust, delays in seeking care, and avoiding medical interventions can contribute to negative obstetric outcome [8].

Psychological and (psycho)sexual problems

Limited research, with methodological limitations has investigated the impact of FGM on sexuality, including orgasm. In Egypt 250 women were examined and interviewed to investigate their psychosexual activity [9]. Results showed that women who were circumcised, complained significantly more of dysmenorrhea, vaginal dryness during intercourse, lack of sexual desire, less initiative during sex, being less pleased by sex, being less orgasmic, and having difficulty reaching orgasm than the uncircumcised women. Other psychosexual problems, such as loss of interest in foreplay and dyspareunia, did not reach statistical significance. A more recent study on 220 women in Egypt [10] showed that women with type II had significantly lower scores of desire, lubrication, orgasm, pain and satisfaction compared with the type I circumcised group. Women with type II had higher scores of depression, somatization, anxiety and phobia than uncircumcised women. There was no significant difference between type I and type II on the psychological assessment.

Research among 66 women with FGM in the Netherlands also found signs of mental health and psychosocial effects as a result of FGM [11]. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were found. Also women with a milder form of FGM reported post-traumatic symptoms. A combination of type III, vivid memory, migration at a later age, low levels of education and inadequate support from the partner were concomitant with serious symptoms. This combination points to the fact that different integrated care models and interventions need to be used in order to reach these women.

Care in the Netherlands – talking about FGM

Many medical professionals find it hard to talk with women about their circumcision. They don’t know how to start, what to say and what to ask. Part of the problem is that professionals rarely meet a woman with FGM and as a result don’t develop this specific working experience. Women with FGM on the other hand are not always able to address their complaints. Some of them aren’t even aware that their complaints are related to FGM [12].

The women’s level of fluency in the Dutch language and the extent to which they feel comfortable in the Dutch (health) care system co-determines whether women talk about their symptoms. Many feel ashamed to talk about the subject. Certainly when the medical gaze is laid upon them, as a Sudanese women stated about when she was in labour:

You feel ashamed, you don’t understand why they are so startled. A lot of service providers came to see me when I was in labour. They would leave the room to talk to each other and then come back to have another look at me. There were about six or seven doctors in the delivery suite with me. I started to feel scared myself… [11]

Care in the Netherlands: consultation desks

Between 2012-2014 a project started to gain insight how to improve health care for women living with FGM. In several Municipal Health Services and a Health Care Centre, a consultation desk was installed. Key persons from practising communities educate women with FGM, refer and sometimes accompany them to the consultation desks. The most important reason to involve a Health Care Centre is that most women present their symptoms to a general practitioner. Problem is that many general practitioners lack the knowledge to identify FGM as a possible cause for the complaints and to discuss this possibility with the women [12].

Reconstructive surgery

Since 2009, reconstructive surgery is possible in the Netherlands. With this surgery the external genitals that are cut away – the clitoris and possibly the labia minora – are recreated. According to a Swiss case study the surgery in combination with psychosexual therapy improves sexual function and has a positive outcome in pain reduction as well as in self body image. The safety and efficacy of clitoral reconstruction has been limitedly evaluated with a maximum of 1 year follow-up. Until more is known about the effects of this surgery, it is advised that this kind of surgery is combined with sexual therapy before and after surgery [13].

A Dutch working group of gynaecologists and a plastic surgeon with a tropical background who performs the reconstructive surgery, is currently writing the protocol Reconstructive Surgery after female genital mutilation.

Conclusion

With more than 29,000 women with FGM in the Netherlands and millions in their countries of origin, it is important for tropical doctors to be aware of the long term health consequences of FGM. With educating medical professionals there is still a lot to win in improving health care for women living with FGM. Showing respect and considering the impact of ancient local customs upon the women may help to reach out and provide the proper care they might need in the future – especially when giving birth.

References

- UNICEF, Female genital mutilation/cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change, 2013.

- Exterkate M, Female genital mutilation in the Netherlands; Prevalence, incidence and determinants. Pharos, 2013.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Female genital mutilation. Fact sheet No 241, February 2014.

- Iavazzo C, Sardi TA, Gkegkes ID, Female genital mutilation and infections: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;287(6):1137-49.

- Amin MM, Rasheed S, Salem E, Lower urinary tract symptoms following female genital mutilation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123:21-3.

- WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet 2006;367:1835-41.

- Berg RC, Underland V, The obstetric consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013. Epub 2013.

- Abdulcadir J, Rodriguez MI, Say L, Research gaps in the care of women with female genital mutilation: an analysis. BJOG 2015;122:294-303.

- El-Defrawi MH, Lotfy G, Dandash KF et al. Female genital mutilation and its psychosexual impact. J Sex Marital Ther 2011;27(5):465-73.

- Ibrahim ZM, Ahmed RM, Mostafa RM, Psychosexual impact of female genital mutilation/cutting among Egyptian women. Human Andrology 2012;2:36-41.

- Vloeberghs E, Knipscheer J, van der Kwaak A, et al. Veiled Pain. A study in the Netherlands on the psychological, social and relational consequences of female genital mutilation. Pharos, 2011.

- Lagro-Janssen T, Hummeling T, Huisarts kan meer doen bij vrouwenbesnijdenis. Med Contact 2015; nr. 5:188-90.

- Abdulcadir J, Rodriguez MI, Petignat P, et al. Clitoral reconstruction after female genital mutilation/cutting: case studies J Sex Med 2015;12:274-81.