Main content

Mental health and psychosocial support

Emergencies, humanitarian disasters, have implications for individuals and communities, also in their aftermath. In mental health care approaches, both the individual mental well-being and the context of the family and community are important elements to be taken into account. Because of their comprehensive approach, such programmes are categorized as mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) programmes.

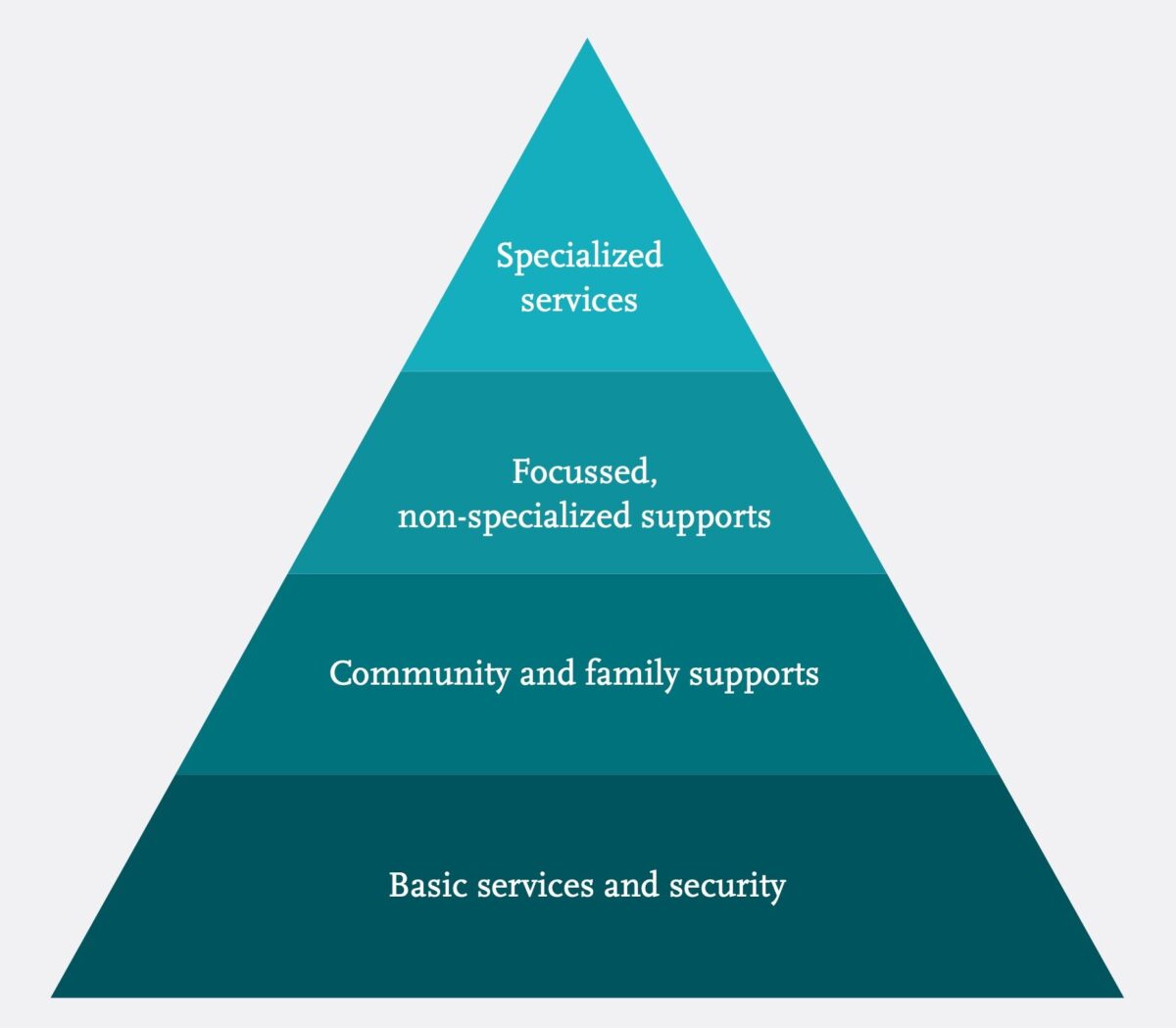

Taking a multi-layered and comprehensive approach in MHPSS is propagated in the IASC Guidelines that were developed by the Inter Agency Standing Committee (IASC, a consortium of international NGOs) on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Despite being developed for emergency settings, the guidelines are applicable for general humanitarian settings as well. Their multi-layered approach is reflected in the intervention pyramid for mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. (figure 1)

This pyramid reflects the needs of people in emergency settings. [1] The base layer refers to basic services and security such as water, food and shelter referring to the protection of the well-being of the population, as well as basic psychosocial assessment and help. The second layer refers to needs of those people who are able to maintain their mental health and psychosocial well-being, provided they receive help in accessing community and family supports. The third layer, the focused, non-specialized supports, represents specific interventions for individuals, families, groups by workers that are trained and supervised. The fourth layer includes psychological or psychiatric services for those whose suffering is intolerable or for people with severe mental disorders. [1] The intervention pyramid suggests that by fulfilling basic needs, less people will need help in a higher layer. Also, offering psychiatric help in emergency settings when people are traumatized, anxious or depressed may not be useful when support at the base layer is also needed.

In (post)disaster situations it is important to adhere to the local setting and values. Taking into account local customs and views is likely to make an intervention more suitable and acceptable. Embedding health care and aid programmes into a local structure, will assist people to find the way to these services and interventions. Moreover such initiatives will be more sustainable. The NGO ‘War Trauma Foundation (WTF)’ works by this philosophy, and invests in capacity building of local care givers, such as teachers, counsellors, social workers, doctors, nurses, parents, refugees. [2]

A good example of a combined layer 2 and 3 approach is the programme in the Northern Caucasus. Teachers and school psychologists were trained in supporting children in difficult situations and in caring for themselves and each other. With layer 2 relating to bringing people together to share and solve problems, while layer 3 relates to focused individual and group interventions.

A MHPSS school-based programme in the northern caucasus

In September 2004 School nr. 1 in Beslan, North Ossetia was taken hostage by a terrorist group. More than 300 children, teachers and policemen lost their lives. This traumatic event had a huge impact on the whole republic of North Ossetia, and motivated child psychiatrist Anica Mikuš Kos and the local NGO Dostizhenia to start a psychosocial programme in schools. Since 2006 WTF has got involved in this programme in Beslan, and in collaboration with local NGOs expanded it to Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan and Kabardino Balkaria.

The general objective of the school-based programme was to improve the psychosocial climate in schools, as a well-functioning school offers a safe, supportive and motivating climate and help for children with special needs. According to Mikuš Kos, the school – after the family – is the most important life space for school-aged children, with an enormous potential to impact on the quality of life, healthy development and psychosocial well-being of children, especially for children in difficult circumstances. Also, the school is embedded in daily life and the community. The programme aimed at reinforcing protective factors and addressing risk factors and daily stressors in the life of children and teaching staff. Some of the protective factors include good and supportive relationships with teachers and peers, good achievements, and being competent and successful in sports or in other activities. [3]

Structure and content of the programme

The ‘Capacity Development Programme’ used the trainers model, in which local trainers and counsellors were trained by international trainers related to WTF. With ultimately trained teachers and local trainers organizing outreach seminars in schools for school counsellors and teachers. They in turn would disseminate the content and messages that came out of the training to colleagues, parents and children. An important message of the programme was what a difference a dedicated teacher and school counsellor can make in a child’s perception of life and his hope for the future. The training emphasized looking for solutions, strengthening existing skills, and coping and resiliency. A guidebook with the most important subjects served as curriculum for the participants.

The majority of the trainers were psychologists, who especially because of their long-term involvement gained knowledge and (training) skills. The teacher training focused on protection and risk factors within schools, but also paid attention to the teacher’s own mental health and psychosocial well-being, and how to deal with children with behaviour/emotional problems and/or learning problems. Furthermore relations and communications with parents were addressed. For example, ‘what can we do for a child living in a dysfunctional family?’ Also attention was paid to dealing with a crisis situation in schools and how to improve the school psychosocial climate.

Reflection and lessons learned

The programme was well received in the three republics. With regard to their own well-being and mental health all participants (trainers, teachers and school counsellors) mentioned that they felt calmer and more relaxed, were more tolerant and felt more self-confident. In addition, they mentioned becoming more sensitive to the needs of children and more proactive in taking on a more proactive role. Improved skills and knowledge helped to communicate better with children and parents, as well as with other school team members. Although all subjects were valued, in particular they appreciated the themes on prevention of burnout, the hyperactive child and the underachieving child. One of the teachers illustrated this as follows:

A problem child in my class ran away from home. I told the police that this boy had no friends and no respect at school, and that all his contacts were based on authority. Then at the seminar I remembered him during the topic: ‘Problem children’. I realized I did not try to understand why a child from a good family can be considered to be a problem. The training helped me to see the situation from the other side. I decided to give the boy more responsible work and to include him actively into class. After a few months he stopped coming late to school, started to visit classes, began to discipline his classmates and corrected his grades in school. Teachers can do a lot for children. By increasing the boy’s self-esteem, he started to believe in himself and found the strength to change himself.

The programme also inspired participants to initiate new events at schools, such as additional meetings with parents and extra activities for children, the development of a first aid manual in case of bomb attacks, and a training for youth on assertiveness to prevent the recruitment by rebels.

The volatile situation in the North Caucasus posed one of the greatest challenges. In terms of logistics, participants had to travel more as trainings were relocated because of bomb attacks causing uncertain and insecure situations. On a more psychological level, the long history of insecurity in the Caucasus requires (re)building of trust in ‘the other’. Bringing participants from different republics together was a challenge, also because of political connotations. The hostage taking of school nr.1 in Beslan and other violent acts are blamed on (amongst others) Chechnyan rebels. Chechnya and Ingushetia have a predominant Islamic religion and culture and there tends to be an anti-Russian attitude, whereas North Ossetia has a Russian orthodox or pagan religious culture and a pro-Russian attitude. It was quite unique that people from different republics participated in a joint programme and found that they actually have lot in common and much to share.

In conclusion, community-based mental health care and psychosocial support are extremely important for individuals and communities affected by war and organized violence. Schools are excellent community institutions to take as an entry point for mental health and psychosocial support. By focusing on the safe and protective role schools have in the life of children, such programmes have the potential to contribute to the mental health of their families and the wider community. They are important elements in prevention and reinforcing resilience, in individuals and within the communities.

Recommended reading

- Intervention, Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas is published by War Trauma Foundation.

www.interventionjournal.com - mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: Mental Health GAP Action Programme (mhGAP). World Health Organization, 2010.

- Patel V, Where there is no psychiatrist. A mental health care manual. 2003, London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- Sliep, Y. (2009) Healing communities by strengthening social capital: a Narrative Theatre approach, Intervention educational materials.

- World Health Organization, War Trauma Foundation and World Vision International (2011). Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers. WHO: Geneva.

References

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee [IASC] [2007]. IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva: IASC

- www.wartrauma.nl

- Mikuš Kos, A. (2005) Training Teachers in Areas of Armed Conflict: a Manual, in Intervention Supplement, Volume 3 Number 2