Main content

Osteomyelitis is a very common problem in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) as a result of exposure to mul-tiple organisms, endogenous or hema-togenous (children) as well as exogenous (adults: infected implants). Intravenous antibiotics can be curative in the acute stage of an endogenous infection (the first 36 hours), but antibiotics are not always available and the patients are seen later. Immediately after the first 36 hours a combination of debridement and antibiotics is mandatory. However, once the infection has become chronic other strategies are required (for instance : im-plant removal). In children it is advisable to wait for 8 months, as spontaneous resorption is possible, even resorption of sequestrae. Moreover, it is advisable to wait for the formation of an involucrum: living bone which bridges the infected area, so that the necrotic tissues can be safely removed. Older people might sim-ply “live” with their fistula, rather than being exposed to a series of operations; lifelong suppressive antibiotics may be indicated. Generally speaking, the first question should always be: “Am I going to improve this patient?” Infected im-plants can be left in place as long as they provide stability, leading to bone union. In all cases the patient should know that recurrences are frequent and that often 3 or 4 reinterventions can be expected.

Incidence

Epidemiological data on osteomyelitis in LIMCs is scarce. Incidence increases with concomitant malnutrition or immunosuppression, associated with parasitic infection. Also osteomyelitis is often misdiagnosed or undertreated. The increase in trauma, notably from road traffic accidents, has resulted in an increase in open fractures and their complications. [1] Therefore, osteomyelitis remains an important problem with important impact on mortality, morbid-ity and quality of life.

Origin and clinical findings

The origin of osteomyelitis can be endogenous (= hematogenous) or exogenous. Osteomyelitis can be acute, subacute or chronic.

Endogenous (hematogenous) osteomyelitis (mostly children)

Acute osteomyelitis is characterized by pain, lethargy, fever (often deemed as caused by malaria), and local inflamma-tory signs. In Africa mainly the infants are exposed (poorly groomed umbilical cord; drips for several weeks). Staphy-lococcus aureus is responsible in the majority of cases, but its preponderance is declining, in favour of Gram nega-tives. The proximal metaphyses of the femur and tibia are the areas of choice, but the infection can extend towards the diaphysis. In infants up to the age of 12 months, capillaries cross the growth plate and can therefore cause septic ar-thritis. In the older child these capillar-ies no longer exist, but an intracapsular metaphysis can also allow the infection to spread to the joint. This is the case for the proximal humerus, the proximal radius and the proximal femur.

Chronic osteomyelitis arises as a result of inadequate treatment, and is already established after 36 hours. The tibia is most often involved, followed closely by the femur. The periosteum will form an envelope of living bone (Figure 1), the involucrum, around the medullary space in order to separate it from the rest of the bone. This envelope thus prevents the dispersion of infected emboli throughout the body, but at the same time also prevents antibiotics to pen-etrate into the marrow. The involucrum bridges the infected area, thus allowing safe removal of all necrotic bone and sequestra. Osteomyelitis lasts a life-time, because one is never sure that it is completely eradicated. Long remissions can alternate with periods of exacerba-tion. The term “years without relapse” is therefore more accurate than the term “cure”. Differential diagnosis should always include TBC, Ewing sarcoma and Sickle Cell disease. A fistula can always lead to malignant degeneration.

Subacute osteomyelitis presents as vague pain and a mild fever for 1 to 3 months, after which it becomes chronic. The subacute form is rising in numbers, also in Africa, at the expense of the acute form, probably because antibiotics are given more easily. A special form of subacute osteomyelitis, under 25 years of age, is the Brodie abscess (Figure 2). In 40% of cases it forms after antibiotic therapy, which has tempered the evolu-tion. Treatment consists of debridement and antibiotics. There is only granula-tion tissue, no pus.

Exogenous osteomyelitis (mostly adults)

Exogenous osteomyelitis forms by adjacency of a wound, foreign body, an osteosynthesis or arthroplasty. As the two latter are also on the rise in LIMCS (just like in developed countries), osteo-myelitis as a result is becoming more and more frequent. In Africa it is less frequent than the hematogenous form. Here the infection is often more superfi-cial, which improves the prognosis.

Classification

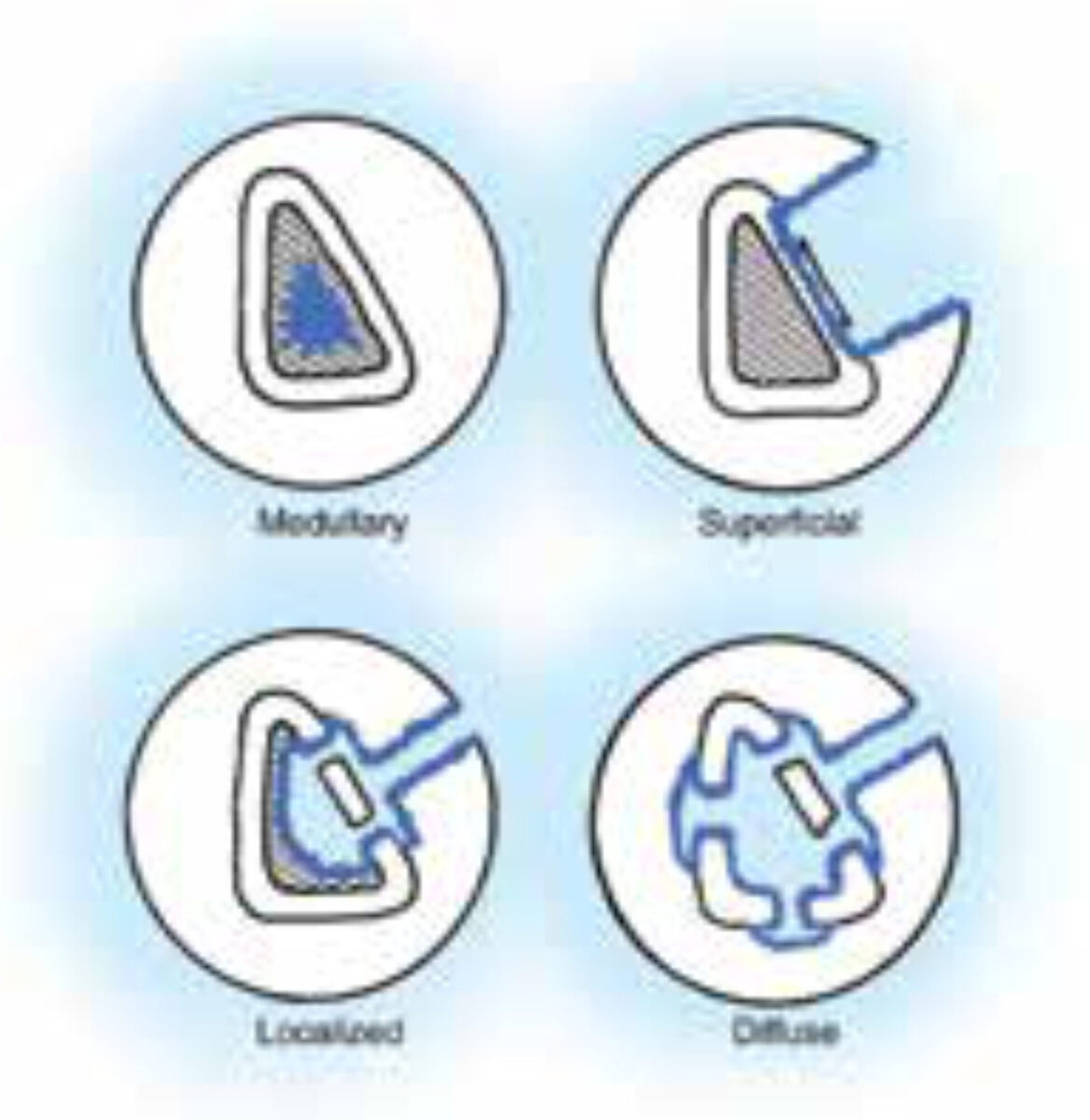

The classification of Cierny-Mader[2] is universally accepted, at least for adults (figure).

- Type I: medullary osteomyelitis.

- Type II: superficial osteomyelitis: involves only the cortical bone and most often originates from direct inoculation or contiguous focus infection.

- Type III: localized osteomyelitis: in-volves both cortical and intramedullary bone. In this stage the bone remains stable and the infection does not involve the entire bone diameter.

- Type IV: diffuse osteomyelitis: involves the entire thickness of the bone, with loss of stability, as in infected non-union.

This classification also takes into ac-count the resistance of the patient:

- A = normal host resistance.

- B = locally reduced resistance (Bl) (e.g. vascular ischemia) or systematically (B2) (e.g. diabetes).

- C = severely compromised patient; not a good candidate for surgery because the intervention could be worse than the disease.

When to operate

One has to consider a conservative at-titude when there is neither pain nor fistula.

In children a waiting period of 8 months after the acute phase is a good option [3], except if a joint is involved. In the first place because the sequesters can resorb spontaneously. Secondly because the infection will become more demarcated. Thirdly, because an involucrum takes time to form; it will ensure continu-ity, so that all necrotic tissue can be removed.

In older patients, not fit to undergo ope-rative treatment, suppressive antibiotic therapy can be considered. A fracture should be allowed to heal first.

In most other cases surgical debride-ment is the key to the treatment. However, a careful risk/benefit analysis should be performed on the basis of the complete medical history beforehand. In doubtful cases, one should consider referring the patient to a colleague with extensive expertise in treating orthope-dic infections.

How to operate

Methylene blue can be injected into the fistulae, 24 hours before surgery, in order to aid complete resection of all infected soft tissue: the necrotic tissues remain blue because they cannot elimi-nate the product.

Pneumatic tourniquet, after hypereleva-tion of the limb, without the use of an Esmarch bandage: in order to facilitate the paprika sign: bleeding bone at decor-tication with a bone biting forceps.

Debridement and sequestrectomy should include all necrotic (blue) bone until one sees bleeding bone (paprika sign). [4] Lavage is important: “dilution is the solution to pollution”. Plates and screws can be left in situ if they stabilize an unhealed fracture.

Dead space can be filled by muscle (saucerization), but nowadays other alternatives are coming on the market, like antibiotic-laden bone cements (Cera-ment©, Bonesupport, Lund, Sweden) [5] and bio-active glass (Bonalive©, Bonalive, Turku, Finland). [6] These are, however, still expensive options and not yet readily available in developing countries. Antibiotic-loaded beads still have their place in the treatment but necessitate removal in a second opera-tion. The author does not advise to leave them in because over time all antibiotics will have diluted out and the beads will become foreign material and covered by biofilm.

Fistulae should be excised and sent for anatomopathology. However, some authors simply curet them or leave them untouched, especially in dangerous areas.

Wounds should be closed primarily if possible. If impossible to do so, granula-tion must be promoted as much as pos-sible, either by appropriate wound care or open techniques like the Papineau technique. [7] Flaps are also possible.

Theoretically, no antibiotics should be administered until deep tissue cultures are taken, in order to determine the causative germ and its sensitivity to antibiotics. But this is rarely possible in Africa. So, if cultures are not possible a combination of amoxicilline/clavulanic acid with gentamycin will cover most Gram+ and Gram- germs, as well as anaerobes. They should be continued for a total of six weeks (2 weeks IV and 4 weeks orally).

Prognosis

Recurrence is always possible during the remaining lifetime, but most often in the first postoperative year. Generally the recurrence rate is about 40% (also up to 30% in the western world). [8] Thus the initial healing rate is in the order of 60%. The experience of the surgeon is the only really significant factor, especially as regards the complete de-bridement. But according to Martini[3] the cure rate rises to 95% if reinterven-tion is performed (up to 4 times!). Also involvement of plastic surgeons through muscle flaps, local or free, increases this percentage, so healing rates above 90% are achieved more often than in the past. [2] Factors favouring the healing are: female gender, location in the humerus, subacute onset, delay in presentation of less than one year, normal or elevated lymphocytosis, normal or lowered poly-nucleosis, small involucrum size and above all: the experience of the surgeon. Results can be further improved by total eradication, but without weakening the bone, causing fractures. If necessary, administration of combined antibiotic therapy and also stopping the smoking habits of the patient.

Conclusion

Osteomyelitis continues to be a patho-logy that causes much morbidity and disability in LMICs, as well as in the western world. Adequate diagnosis and treatment can greatly improve outcome and therefore the aim should be to treat this condition as quickly and thoroughly as possible.

References

- Museru LM, Leshabari MT, Grob U et al. The pattern of injuries seen in patients in the orthopaedic/trauma wards of Muhimbili Medical Centre. East Centr Afr J Surg 1998;4:15-21.

- Cierny G 3rd, Mader JT, Penninck JJ, A clinical staging system for adult osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;414:7-24.

- Martini M, The treatment of chronic hematogenic osteo-myelitis. Acta Orthop Belg 1981;47:79-84.

- Tetsworth K, Cierny G 3rd, Osteomyelitis debridement techniques. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; 360:87-96.

- Ferguson JY, Dudareva M, Riley ND et al. The use of a biodegradable antibiotic-loaded calcium sulphate carrier containing tobramycin for the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a series of 195 cases. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B: 829-36.

- Lindfors NC, Hyvönen P, Nyyssönen M et al. Bioactive glass S53P4 as bone graft substitute in treatment of osteomyelitis. Bone 2010;47:212-8.

- Panda M, Ntungila N, Kalunda M et al. Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis using the Papineau technique. Int Orthop 1998;22:37-40.

- Tice AD, Hoaglund PA, Shoultz DA, Risk factors and treatment outcomes in osteomyelitis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003;51:1261-8.