Main content

I sneezed. Wrong timing. My caretaker flinched. ‘I always get a cold from the air-conditioning on the plane’, I quickly mumbled. I had just arrived in Sierra Leone amidst the exponential rise of the pandemic, and any sneezing white person was treated as a potential biohazard. This country knows how to deal with outbreaks. From the very start, Covid-19 was approached the same way as Ebola. While wreaking havoc in Europe and the USA, Covid-19 numbers were still low in Africa. However, Sierra Leone had already closed its airspace and borders for non-essential supplies. A state of emergency was declared, schools were closed and a lockdown put in place until further notice. All this, without a single confirmed case in the country. These decisions do not come without consequences. The country is largely dependent on imports of vital commodities: food, non-consumables and – not least for the hospital – pharmaceuticals. Food prices increased and medicine stocks slowly ran low as most exporting countries kept supplies to themselves. Suddenly some patients had to pay for their medication. Normally in Sierra Leone, health care for children under five years of age and for pregnant women is provided free of charge, but if drug stock runs dry, eventually, patients will have to pay.

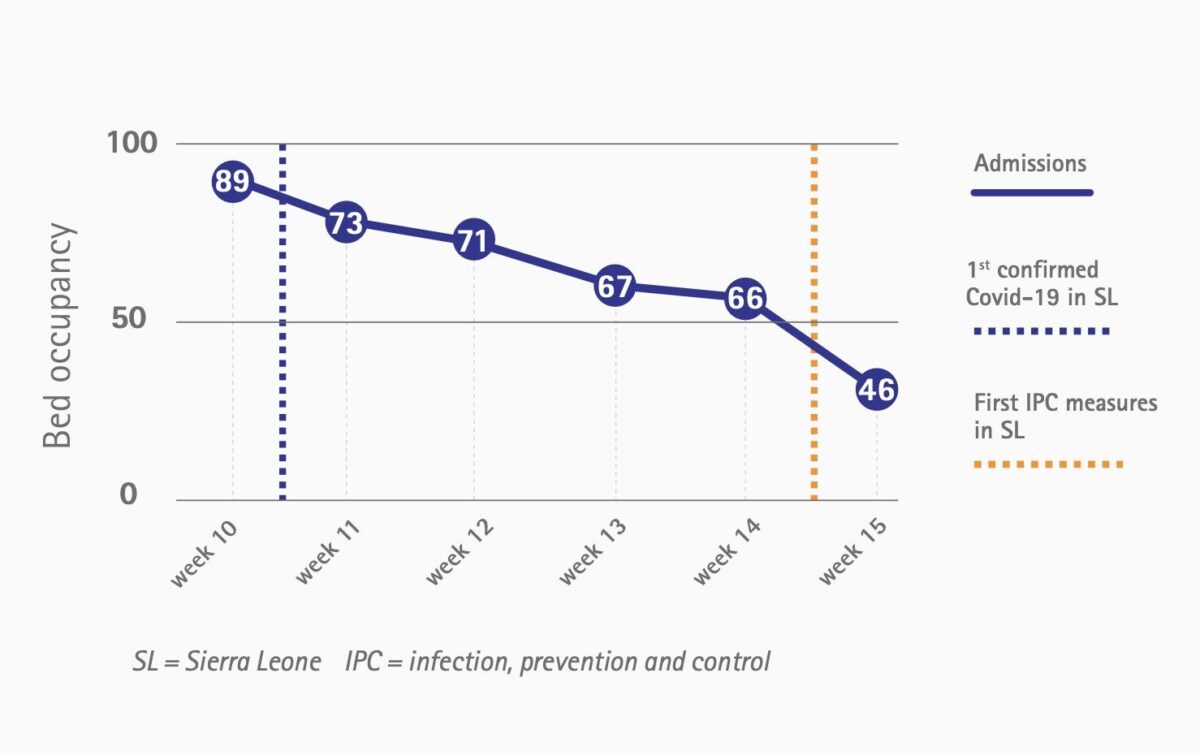

Halfway through March, at the general hospital meeting with all employees present, the fear was tangible. Ebola is more of an open wound than a scar. Everyone knows someone, or knows someone who knows someone who died of Ebola. It is hard to explain to people, even the skilled health care workers, that this virus is less fearsome than its highly lethal haemorrhagic counterpart from only five years ago. Not surprisingly, the utter paralysis of the developed world and its crashing economies do not temper the fear. Not only were the personnel scared. A steep decline in hospital admissions followed after downscaling the hospital to just emergency operations [Figure 1]. When I asked my landlord what people’s reasoning could be to stay away from the hospital, she told me that they feared to contract corona at the hospital, but more importantly, they feared to be isolated. Logically, suspected corona cases are kept in isolation until the test results become known. The same happened during the Ebola outbreak. Isolation alone had repercussions, regardless of the test result. Negatively tested Ebola suspects as well as survivors were stigmatised and sometimes excommunicated. Not a surprise then that Sierra Leoneans feared a repetition of this with corona.

Until now, two-and-a-half months after the first case got detected, Sierra Leone has not follow the exponential path that many other countries have, at least if we go by the official numbers. Although the risk factors are limited with fewer old people (life expectancy is 54 years), less obesity, and less smoking, we didn’t know how HIV and tuberculosis patients and malnourished patients would be hit. Recently, we had our first case in the hospital. Because the government still anxiously carries out extensive contact tracing (even though clear community spread is present), many mostly asymptomatic staff had to be quarantined. Hence, the hospital was forced to scale down even further as did several other health facilities. It goes without saying that this has devastating consequences for a country with already dramatically low numbers of health workers. Like in previous disease outbreaks, the provision of routine health care suffers. Many villagers, including our landlord, turned out to suffer from some sort of ailment. With a dry cough, low grade fever, muscle pain and anosmia she insisted she had malaria and sought treatment for it. I let her take her own decision. The fear is clearly still present, and I cannot blame her. I am however comforted that the majority of people will recover from this disease smoothly. Over here, compared to Ebola, corona is a shark without teeth. The real dangers are the repercussions of the governments’ containment strategy.

I felt like I had to help, not only because I wanted to, but because it is my duty as a global health doctor