Main content

In Mpumalanga Province, South Africa, teenage pregnancy rates as well as unintended pregnancies are ex-tremely high. (1) Family planning services are available but basic, proper explanation and informed consent is unavailable, and several other barriers to good family planning services exist. Six out of 28 hospitals offer ter-mination-of-pregnancy services. Because of a largely unmet need for family planning and access to safe abor-tion services, many women decide to go to backstreet ‘doctors’ performing illegal abortions. (2)

Long-acting hormonal sub-dermal implants have proven very effective in reducing teenage and unwanted pregnancies. (3) In June 2014, South Africa rolled out a programme to freely provide this type of contraceptive for all women of childbearing age. Professional nurses and midwives from clinics and hospitals were trained on insertion of the implants. Subsequently, clinics and hospitals were stocked with the product, after which things moved quickly. The response among women was positive, and within the next six months over 6000 women in Mpumalanga received the implant. Many unintended pregnancies were prevented, and dangers related to abortions and ectopic pregnancies were averted in all these women. It seemed the need for family planning was finally going to be met. Unfortunately, it turned out that the demand was higher than the supply.

Challenges

In order to meet the demand, the initially trained nurses were encouraged to transfer their skills within the healthcare facility. They trained their colleagues, who in turn trained student nurses. Within a short time, these student nurses were placing most of the implants, and along the way many skills got lost in translation.

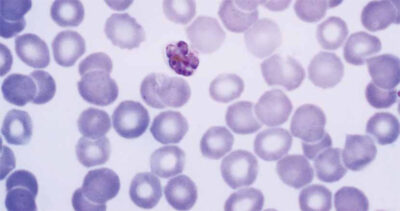

With a loss of the necessary training and skills, the placement of the implants was not always done correctly. Due to incorrect placement, several cases of implant migration were reported and in some instances even into the circulatory system and distant organs.

The second challenge was the interaction with cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inducing drugs. (4) With an HIV prevalence of about 36% amongst women attending antenatal clinics (5), many women in Mpumalanga are on antiretroviral drugs or tuberculosis (TB) treatment. Interaction of levonorgestrel with these drugs could lead to decreased bioavailability of the hormone, increasing the risk of pregnancy. Healthcare workers were advised to refrain from insertion of the implant in any patient with HIV or TB. One could argue that it might be a better option to let the patient make an informed decision while advising the concurrent use of barrier contraceptive methods.

But the third and probably most important challenge was the lack of proper counselling before insertion of the implant. Good counselling is essential for each woman to make an informed choice on her contraceptive use. In a population with already high levels of discontinuation of contraception, many women will resort to abortions. (5) Although healthcare workers were trained in providing counselling to women, in practice counselling was inadequately done. The biggest resulting problem was the lack of an explanation of the possible effects of the device on menstruation. It is known that the implant can lead to altered or absent menstrual periods. If these and other (especially transient) side effects are not communicated properly, women will have false expectations, and many will not be satisfied with the implant. One should also consider the importance of cultural beliefs in this regard. In some cultures. the lack of menstrual periods is unacceptable.

Within six months after insertion of the implant, many women came back with the request to have the implant removed. The reasons mentioned were mainly related to cultural beliefs. Women were ‘feeling hot’, had a ‘feeling the blood was accumulating in the body’, ‘veins were becoming swollen’ and they had ‘abdominal pains because the blood did not come out’. Other side effects mentioned were heavy bleeding, libido changes and headache. No woman mentioned the wish to become pregnant as the reason for request of removal. Attempts by healthcare workers to convince the patient of the safety of the implant were at this stage unsuccessful, as counselling should have been done before insertion. Because nurses at the clinics lacked the resources to remove the implants, they had to refer these patients to a hospital, further increasing the workload for doctors and hospital nurses.

Source: WIKIHOW

Conclusion

Due to these challenges, the insertion of the implant was suspended in Mpumalanga province, six months after initiation. A survey was performed with the goal of improving the programme. But even if the programme is improved and restarted, challenges will remain, as suspension of a programme can be bad for its image.

When healthcare professionals are trained to provide this service, their skills should be regarded as exclusive and not transferable within the facility, e.g. by awarding a diploma and empowering patients to ask for this proof of training. With increased demand, the number of procedures that can be done in a certain time frame will be less, but quality should be more important than quantity. More focus should be placed on counselling, especially with regards to cultural beliefs. An outreach campaign solely for counselling, and without direct insertion, leaving the women with sufficient information and time to make an informed choice on their contraceptive use, should be considered. Interactions with other drugs should be properly investigated and communicated before a programme is rolled out. And finally, healthcare workers trained to insert an implant should also be trained and provided with resources for removal.

Nevertheless, it is impressive that an effective long-term contraceptive can become available free-of-charge for so many women with a need for family planning. In learning from these challenges, we can only hope that many more women in South Africa will be able to have access to long-term family planning services and to make an informed choice. We will then be able to further decrease the numbers of unwanted pregnancies and induced abortions, thereby saving the lives of many women and improving the lives of families and children.

References

- Mchunu G, Peltzer K, Tutshana B, Seutlwadi L. Adolescent pregnancy and associated factors in South African youth. Afr Health Sci. 2012 Dec; 12(4):426-34.

- Jacobs R, Hornsby N, Marais S. Unwanted pregnancies in Gauteng and Mpumalanga provinces, South Africa: examining mortality data on dumped aborted fetuses and babies. S Afr Med J. 2014 Dec; 104(12):864-9.

- Secura, Madden et al NEJM 2014.

- https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv-guidelines/285/nnrti-drug-interactions

- van Bogaert LJ. ‘Failed’ contraception in a rural South African population. S Afr Med J. 2003 Nov; 93(11):858-61.

- http://www.avert.org/south-africa-hiv-aids-statistics.htm