Main content

Setting

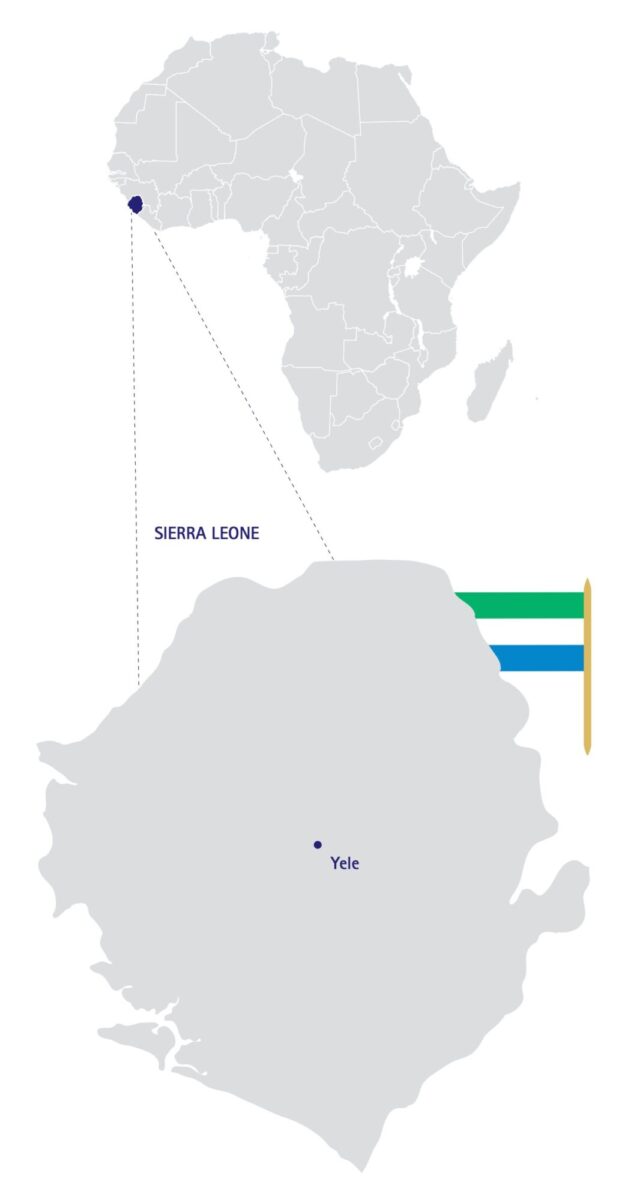

The Lion Heart Medical Centre is located in Yele, a small town in the middle of Sierra Leone. This new rural hospital opened in 2012 and has a capacity of 32 beds divided in a male, female, paediatric and maternity ward. The medical staff consist of one medical officer, two clinical health officers and qualified local nurses. It has a surgery room, basic laboratory facilities and digital radiography equipment. The nearest specialist hospitals are six hours away by car.

Case report

A six-year-old boy known to have sickle cell disease was admitted into hospital with a swollen and painful right upper arm and upper leg. There was no history of trauma. About one month ago the child had been treated in another hospital, because of a swelling in his right upper arm that had been drained. His mother did not know if any pus had been collected during that intervention.

During physical examination he looked ill; the temperature was normal. His right upper arm and upper leg were swollen and there was a healed scar in the middle of the dorsal side of the upper arm. Passive and active movement of both extremities were very painful and limited. The right leg was shortened. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 70 mm/hour; C-reactive protein (CRP) and white cell count (WCC) were not measured. X-rays showed evidence of severe osteomyelitis in both femur and the right humerus. There was an epiphysiolysis of the right femoral head; the caput was intact but there was a spiral fracture of the proximal femur (x-rays 1 and 2).

The boy was treated with cloxacillin, ibuprofen, folic acid and skin traction of the right leg. Because of the severity of the osteomyelitis, CONSULT ONLINE was asked for advice on further treatment.

Advice from the specialists

Four specialists responded within three days. All shared the opinion that in this complex case treatment would take long and prognosis would probably be poor.

Importance of testing for HIV and tuberculosis was emphasized as was preventing and treating anaemia, malnutrition and decubitus. Therefore, it was advised to combine skin traction of all affected bones with passive exercise of free joints.

In acute osteomyelitis the initial choice of intravenous antibiotic treatment could be flucloxacillin, pending culture results of drained pus, blood or a bone biopsy. If there is no clinical improvement after a few days, surgical intervention is necessary. Pus collections should be removed and ultrasound can be a helpful tool to localize these collections. To prevent instability of bones after surgery, bone sequestra should only be resected if enough surrounding bone has been formed.

Treatment can be monitored with clinical parameters, haematological markers and medical imaging. Antibiotics can be switched from intravenous to oral if there is clinical improvement. In case of chronic osteomyelitis antibiotic treatment is not indicated, as this would have no effect on dead bone and would only select resistant bacteria.

Despite maximal traction, prognosis of the epiphysiolysis would probably be poor.

Discussion

Osteomyelitis is inflammation of the bone with bone destruction. The differential diagnosis includes soft tissue infection, cellulitis, septic arthritis, trauma and malignancy. The long bones, and especially femur and tibia, are mostly affected. The route of infection can be from external trauma or through haematogenous spread and can be acute or chronic, when treatment is insufficient or delayed. [1-3]

Incidence numbers in developed countries vary from 2 to 13 per 100,000 children. [2,4]

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative organism, but in children with sickle cell anaemia Salmonella spp. and S. pneumoniae can also cause osteomyelitis. [1-3]

Risk factors include trauma and recent systemic infections. Children with sickle cell anaemia have a higher risk of developing osteomyelitis, and in these cases multifocal osteomyelitis is also more common. [2]

Most of the children with osteomyelitis will present with pain, swelling and limited function of the affected part of the body. [2-4] About 40% of the children will not have a fever on presentation. [2] In resource-poor settings children will probably reach medical care late and therefore are likely to have advanced disease on presentation.

Inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP will be elevated in most cases, but because CRP has a faster response to disease activity, it is a better marker to monitor treatment. [2-4]

Plain radiographs can support diagnosis and exclude other diagnoses. Bone damage only becomes visible after about two weeks. Ultrasound can be used to localize and drain fluid collections. [2-4] Other imaging modalities such as MRI, CT or bone scans are not available in resource-limited countries.

In uncomplicated osteomyelitis, a course of intravenous antibiotics that includes cover for Staphyloccus aureus, can be given that may be switched to oral treatment for three more weeks. Antimicrobial sensitivity testing is helpful to guide the antibiotic choice if available. Temperature above 38.4 °C and CRP above 100 mg/L are important indicators to continue intravenous treatment. [2] Surgery intervention is an option if there is no clinical improvement on antibiotic therapy after 3 days or if there are big pus collections[1-2].

Conclusion

In this case report we presented a young boy with sickle cell disease and severe multifocal osteomyelitis. It underlines the need for early detection and treatment of sickle cell crises and/or osteomyelitis.

However, this case also shows that even without expensive diagnostic and treatment facilities, local health workers in low-income countries can diagnose and treat this complication, thus reducing morbidity and prevent disability.

References

- Faust SN, Clark J, Pallett A, Clarke NMP. Managing bone and joint infections in children. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:545-53.

- Dartnell J, Ramachandran M, Katchburian M. Haematogenous acute and subacute paediatric osteomyelitis. A systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94-B:584-95.

- Roord JJ, Kimpen JLL. Infectieziekten. In: Brande JL van den, Heymans HSA, Monnens LAH, eds. Kindergeneeskunde. Maarssen; Elsevier gezondheidszorg: 1998. P. 374-409.

- Dodwell ER. Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children: current concepts. Curr Opin Pedatr. 2013;25:58-63.