Main content

Setting

The Lion Heart Medical centre is located in the small town of Yele in the centre of Sierra Leone. This rural hospital is staffed with 2 Dutch tropical doctors and local clinical health officers. There are 50 beds available for patients and the facilities are basic including ultrasound, laboratory, X-ray, operating theatre and an outpatient clinic. The nearest referral possibility is available in Freetown, a 6-hour drive away and even longer by public transport.

Case

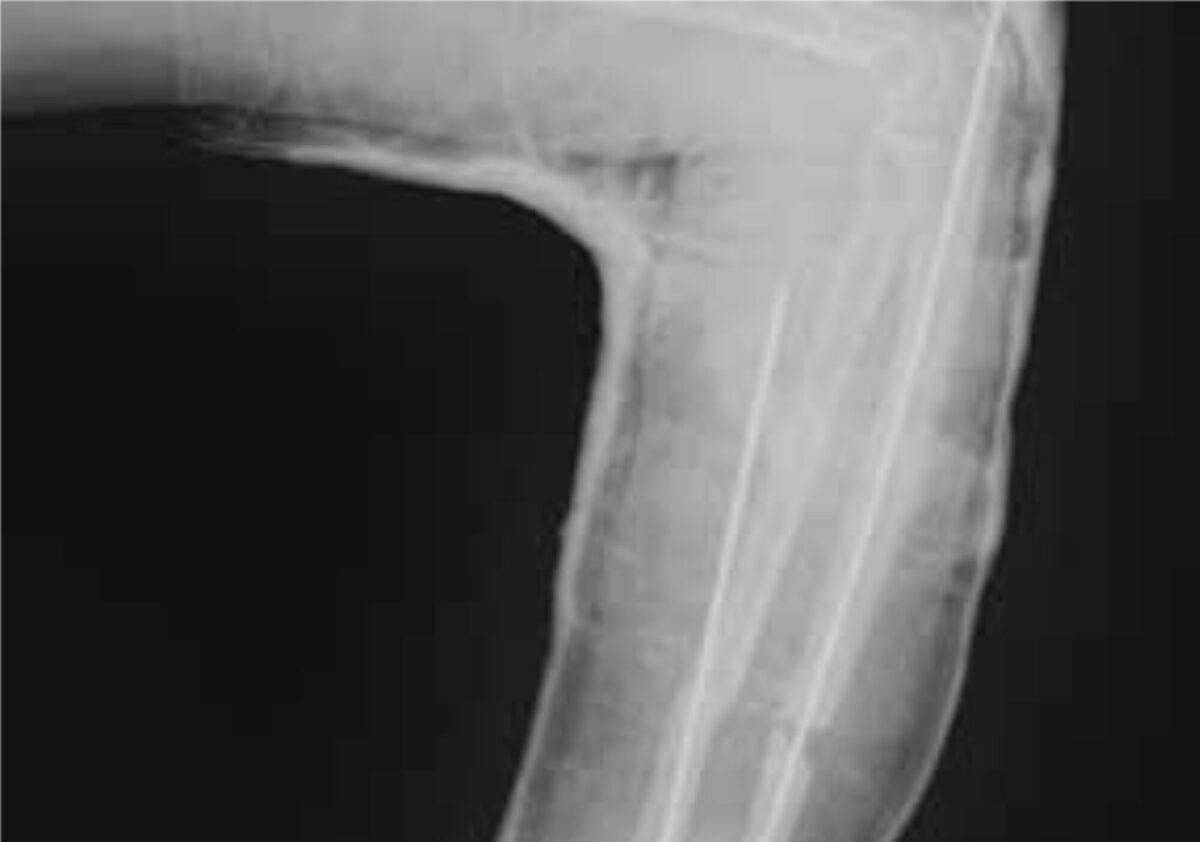

A 29-year-old man presented at the outpatient clinic with a small bandage on his left arm; he had injured his arm three months before in a motorcycle accident. He had first gone to the traditional healer, but after three months there was no significant improvement. Upon clinical examination abnormal mobility was felt midway in his lower left arm. No wounds or scars were observed and his left hand had normal function. The X-ray showed a midshaft fracture of both ulna and radius (figure 1). Initially plaster of Paris (POP) was applied under traction for three weeks to improve position.

Specialist advice

The surgical and orthopedic specialists were asked for their treatment advice for this 3 months old fracture. Within 48 hours the specialists responded and they all agreed that an operation would be the best treatment for this non-union. It was discussed that it would be a difficult procedure and therefore they advised to explore the possibility of having a visiting surgeon assist in this procedure. It was also suggested that there might be a slight chance the fracture would also heal with POP extended to the upper arm.

Treatment

The above-mentioned possibilities were discussed with the patient and he preferred to be operated in The Lion Heart Medical centre at short notice. With the help of detailed instructions from the specialists the procedure was carried out. In theatre, the old callus was scraped away from the fracture ends and both the radius and ulna were fixated with metal pins (k-wires). Unfortunately the X-ray (figure 2) showed that the pin through the radius was misplaced and therefore had to be removed immediately after the procedure. POP was applied to the upper and lower left arm for six more weeks, after which the second pin was removed. POP was applied again for three more weeks.

Result and follow-up

Nine weeks after surgery the POP was removed. Clinically the ulna was reunited, but the radius was not, probably due to misplacement and removal of the metal pin.

Unfortunately at that moment the X-ray device was out of order, so imaging of the final result was not available. However, most importantly the left arm was functional again. The wrist joint functioned normally and flexion and extension of the elbow joint was also possible. Pronation and supination of the lower left arm were restricted due to instability of the radius. The main outcome was that the patient was able to grab and hold objects again with his left arm due to the stability of the ulna. Therefore the patient was very pleased with the final outcome.

| Box 1. Non-union of a fracture Incomplete healing of a fracture in which both cortices of the bone fail to join is called a non-union, which commonly presents with continuing pain, swelling or instability. Common causes for non-union include poor fixation leading to excessive movement at the fracture site, insufficient apposition of the bone fragments where the fragment ends are too far from each other and inadequate blood supply to the fractured bones (this is common for example in fractures involving the scaphoid and proximal fifth metatarsal bone). Fractures with severe soft tissue injury, for example high-energy trauma, are also more at risk for a non-union. Other predisposing factors include chronic disease, malnutrition, immunosuppression, malignancy and local infections. [1] |

| Box 2. Fracture treatment by traditional healers The role of the traditional healer is important. In many African countries fractures are frequently treated by a traditional healer, a person who is recognized by the community as competent to provide health care based on cultural, social and religious beliefs. Their methods include reposition, massage of the affected body part to improve blood flow, application of herbs and fixation with wooden sticks, leaves or bandages. Although fracture treatment by traditional healers is very common in large parts of Africa, their methods and outcome have not been well evaluated. A review from Nigeria regarding the practice of traditional bone setting describes the main complications, which include limb amputation because of gangrene caused by tight wrapping, osteomyelitis, non-union, mal-union and joint stiffness or dislocation [3]. Local experience from the Lion Heart Medical Centre in Sierra Leone regarding traditional fracture treatment includes mainly the application of herbs and poor immobilization with wooden sticks. Sometimes hot boiled herbs or burning leaves are applied causing burns leading to an increased risk of infection and osteomyelitis. In severe cases these injuries have resulted in amputation of the limb. |

References

- Howe A, Eiff P, Grayzel J. General principles of fracture management: Early and late complications. Up to date, accessed 7-5-2014.

- Aries M, Joosten H, Wegdam H, van der Geest H. Fracture treatment by bonesetters in central Ghana: patients explain their choices and experiences. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:564-74.

- Dada A, Yinusa W, Giwa S. Review of the practice of traditional bone setting in Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2011;11:262-5.