Main content

Setting

Endulen Hospital is located in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) of Tanzania. It has 70 beds. The hospital opened in 1976, and provides care in an area of approximately 8,300 km² where around 90,000 Masai people live.

Case report

Recently, a 72-year-old female patient was admitted with a suspected case of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) or Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), following the administration of ciprofloxacin. She received ciprofloxacin for the treatment of typhoid fever and was discharged after a short admission.

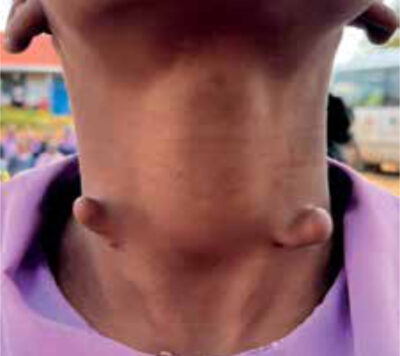

Upon readmission, five days after the last dose of ciprofloxacin, she presented with “sudden onset” blisters that had ruptured. Initial examination revealed that the affected skin closely resembled burn injuries (see attached figures). Approximately 45% of the total body surface area (TBSA) was involved, specifically the thorax, abdomen, neck, back, face (including membranes of eyes and mouth) and genitalia. The legs were mostly spared, and the capillary refill time was normal. All vital signs were normal, the initial full blood picture showed a white blood cell count of 5.8 x 10⁹/ L, haemoglobin 13.5 g/dL and platelets of 403 x 10⁹/ L, HIV test was negative. Based on these findings, superficial partial-thickness burns were suspected. Eating was challenging since she had difficulty opening her mouth. Her urine output was around 25-30ml per hour, and she has not shown any signs of fever. She received treatment with daily cleaning and dressings, intravenous fluids, pain management, prednisolone and antibiotics (ampiclox). The differential diagnosis included suspected TEN / Stevens-Johnson syndrome, while Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS) was considered less likely. Referral to a specialised centre for comprehensive testing (electrolytes, kidney function, etc.) and ICU care/burn unit in Mount Meru Hospital (Arusha) was planned. However, this was complicated by distance, costs and road conditions. Therefore, Consult Online was consulted for additional treatment recommendations.

Questions for the dermatologists:

- How likely is our suspicion of TEN/SJS?

- What is the role of corticosteroids in the management of TEN/SJS?

- Is honey wound treatment sufficient, or would there be other recommended treatments? Any preference for antibiotics?

- What further steps should be taken in the treatment and care of this patient?

- What are the recommendations for nutritional support (nasogastric tube/high-protein diet) due to potentially affected mucous membranes?

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) is a rare and potentially life-threatening muco-cutaneous disorder. [1] TEN results from extensive cell death at the dermal-epidermal junction and above, leading to significant areas of epidermis being separated from the dermis, which manifests as “scalded skin”. The exposed skin can lead to considerable losses of electrolytes, albumin and water. Typical symptoms include extensive mucous membrane involvement, high fever, and intense “skin” pain. The onset of the disease is usually triggered by medications or their metabolites (antibiotics/antiviral, anti-epileptic and NSAIDs), or less frequently by infections, tumours, and vaccinations. TEN is more common in Asian and black people, females and elderly people (50-70 yrs of age). Drug-induced TEN is more common in adults, while infections are the main cause in children.

In low and middle income countries (LMIC), TEN is relatively common. It is relatively frequently observed in HIV patients due to the use of drugs such as nevirapine and sulfa-containing drugs (cotrimoxazole), which are recognised for their potential to cause TEN. Fansidar, another sulfa-containing drug, used as an anti-malarial, is another well-known trigger.

The main treatment for TEN is supportive care until the skin heals, including fluid resuscitation, pain management, wound care, and nutritional support. Early management should focus on stopping the triggering drug and referring the patient to a burn unit or ICU. Taking these steps within 24 hours of blister formation can reduce infection rates, shorten hospital stays, and improve survival.

Advice from the dermatologist, surgeons and burn care unit Rotterdam

Four specialists replied within three days. They all agreed on the diagnosis of TEN. Based on the pictures, the skin appears to be healing already. For obvious reasons, the causative drug ciprofloxacin must be stopped if not already done. The best treatment advice for TEN in LMIC is summarised in the case report by Mwageni et al. [2] The management of skin failure is most important. This means that hydration status, electrolyte and protein losses, and hypothermia should be monitored closely. Moreover, signs of bacterial infections must be checked regularly, since pneumonia (when bronchial epithelium is involved) and sepsis are the most life-threatening complications. Antibiotic treatment must be started only when a superinfection is suspected. Macrolides are preferential.

Wound care has to be done carefully by avoiding excessive touching: daily dressing with Vaseline gauze or silver dressings if available. The authors used honey for some time with reasonable results.

The mucous membranes including the eyes, the mouth, the trachea, the bronchi and the genitals should be cared for. This includes daily use of ocular lubrication and hygienic mouthwashes.

Corticosteroids were advised with intravenous dexamethasone 1.5mg/kg for three days. The use of high doses early in the course of the disease may reduce morbidity and mortality. However, supporting evidence is still unavailable.

Potential albumin loss can be compensated for by high protein foods. One specialist also recommended starting her on high-dose vitamin D, if available. This is associated with better wound healing and less septic complications.

Follow-up

During her admission, the advice of the specialists was followed, but several challenges were encountered. There were multiple failures in placing cannulas due to the damaged skin and subsequently difficulties in keeping the patient hydrated. Daily dressings with Vaseline and honey gauzes were performed. General hygiene measures were challenging to implement, and as a result, she was on preventative antibiotic treatment despite the absence of any signs of infection. Providing her with protein-rich nutrition was difficult because of the scarcity of nutritious food and insufficient funds. Moreover, the advised high dose of vitamin D was not available. On January 13, 2025, she was referred to the specialist hospital (Mount Meru Hospital) in Arusha. The family had raised enough money, and she was hemodynamically stable, with a good urine output and no signs of infection. Unfortunately, she passed away two days later. The exact cause remains unclear due to communication issues. The hospital, doctors, and nurses have been unreachable for days.

References

- Labib A, Milroy C. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. 2023 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. PMID: 34662044.

- Mwageni N, Masenga JE, Mavura D, and Naafs B. (2017). Management of TEN in developing countries: Care and Clinical skills. 2017. 2(1): 1002.