Main content

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death from infectious diseases for children of all ages globally. Children with vulnerable immune systems, such as the very young, HIV-infected or severely malnourished, are most at risk of falling ill or dying from tuberculosis.[1]

A diagnostic gap in children with tuberculosis refers to the discrepancy between the actual number of children with tuberculosis and the number of cases that are detected and reported by healthcare systems. This gap is primarily due to the challenges of diagnosing tuberculosis in children, such as the non-specific symptoms of the disease, the difficulties in obtaining good quality samples for microbiological testing, and the limitations of current diagnostic tools in detecting tuberculosis in children. As a result, many cases of childhood tuberculosis are not diagnosed, treated, or reported.[2] In addition, the low bacterial load of tuberculosis in children, which confers a lower risk of disease transmission, has made the identification and treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in this age group a lower priority than in older individuals.[3] Also, national tuberculosis programmes tend to allocate lower priority to children in terms of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberculosis. However, in the last decade there has been more awareness about TB paediatric cases [4], and with surveillance and mathematical modelling, the estimation of paediatric TB incidence has become more accurate.[2,3]

Personal experience

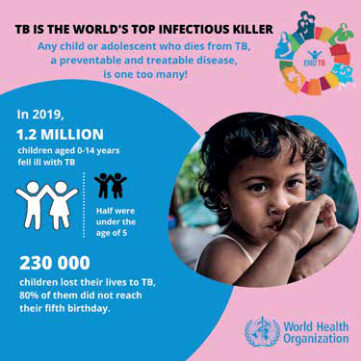

In many cases you can be impressed by reading information like TB is the world’s top infectious killer (figure 1). However, the full realization often only happens when you are confronted with the personal stories of the patients. That is what I realised when I was working for a few months in 2022 in Tygerberg Hospital (Stellenbosch University, Cape Town). South Africa has one of the highest TB rates in the world, and during a normal working day on the paediatric emergency ward you see many cases of TB. Two patients’ stories illustrate this:

- A happy toddler of 3 years old: his mom tells us that he was always smiling, playful and giving the family so much joy. Now this little boy is admitted at the emergency ward in coma with TB meningitis. The boy was hospitalized for a long period and is now suffering from long-term neurological complications (including hydrocephalus) and sitting in a wheelchair.

- A 5-year-old girl living with HIV and multi-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB; resistant to at least two of the most important first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin) is showing us how many pills she needs to take per day for a minimum of 6-9 months! The pill burden is high, and the tablets are not child-friendly in formulation, size or taste.

Figure 1: World Health Organization

During my stay in South Africa, I met highly motivated and active health care workers who want to make a difference. One of them is Marieke van der Zalm, a Dutch paediatrician, clinical researcher and Associate Professor working for the Desmond Tutu Tuberculosis Centre (DTTC); see box 1. In this interview, she tells us about her career, about paediatric TB, the importance of having a research centre, and her dreams for this centre.

From dutch paediatrician to (associate) professor in south africa

Since her medical training, Marieke van der Zalm has had a special interest in paediatric infectious diseases and lung health. Her initial work as an undergraduate student on the role of respiratory viruses in children with cystic fibrosis (CF) resulted in her PhD at the paediatric pulmonology department at Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital in Utrecht on “the role of respiratory viruses during the first year of life” in 2009. After completing her PhD, she specialized to become a paediatrician (at University of Utrecht). Based on her strong interest in working in sub-Saharan Africa, she completed part of her clinical training in paediatrics at Tygerberg Hospital, Stellenbosch University in South Africa and later also at Red Cross Childrens’ Hospital in Cape Town. Van der Zalm told me that both clinical training periods in South Africa were hectic and confronting but also a beautiful life-changing experience. During this time, she realised that her passion was to do research in order to improve health care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like South Africa, by performing highly relevant clinical research to address the pressing health care issues experienced in these settings. In 2014, she started working at the DTTC, Stellenbosch University, and has since received multiple grants for her work on lung health in children with pulmonary tuberculosis.

Looking back on her working life path, van der Zalm sees a common line going through all the work she did, by following her ambitions and dreams and working in her field of interest. This also included working in infectious disease together with pulmonary diseases, working in sub-Saharan Africa, doing clinical research, and maintaining a strong network of health professionals on a global level.

| Box 1: Desmund Tutu Tuberculosis centre (DTTC) – Stellenbosch University The Desmond Tutu Tuberculosis Centre (DTTC) is an academic research centre located in the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Cape Town, South Africa, established in 2003. In 2004, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, who suffered from tuberculosis as a child, became its patron and the centre was formally named. South Africa has one of the highest Tuberculosis (TB) rates in the world. The DTTC adopts an outward focus on a holistic approach toward understanding and combating the TB and HIV pandemics. Their vision is to have a TB-free world for the next generation. Their mission is to be a global leader in TB and HIV research. Research areas are: Paediatric TB (including Lung Health), Health systems and operational research and HIV prevention. [11] |

Paediatric tb diagnosing – closing the gap

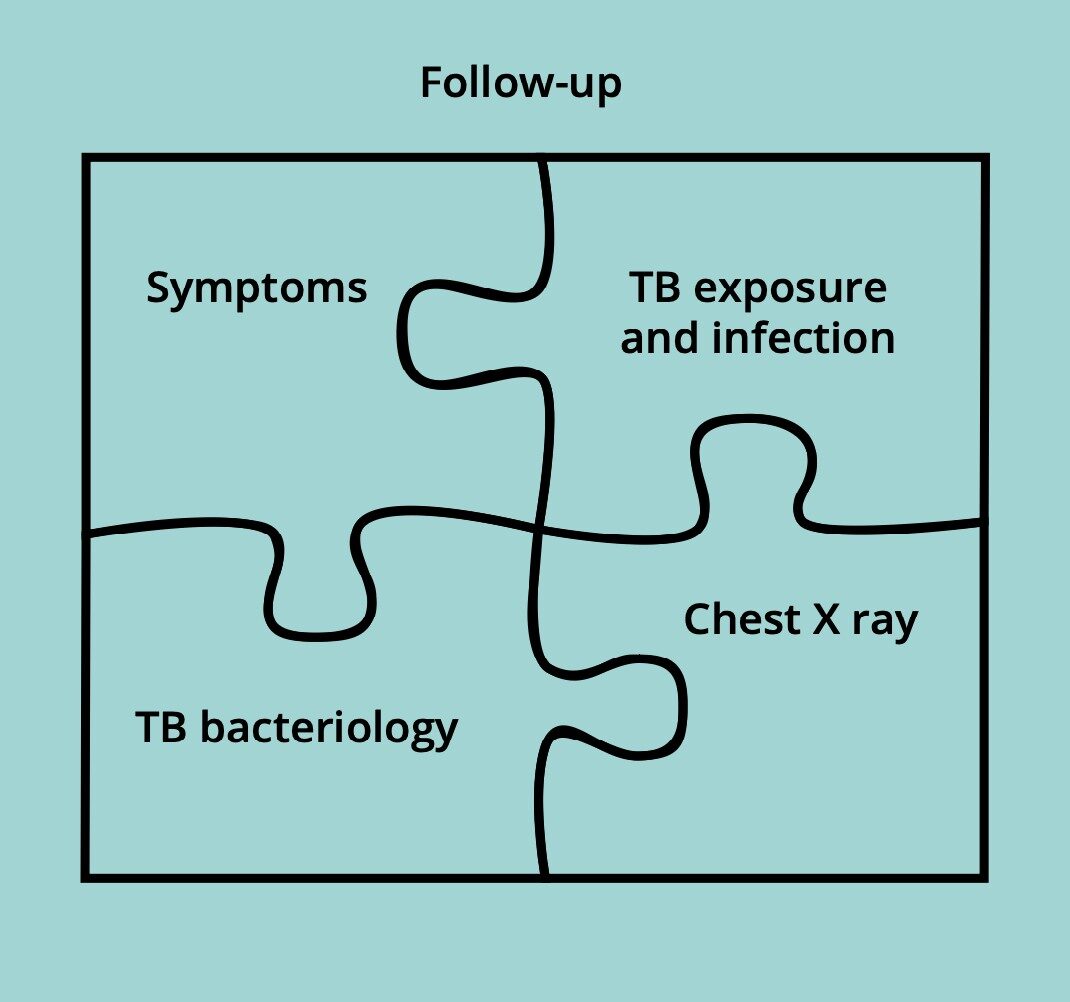

TB is a preventable and treatable disease, but the diagnosis of childhood and adolescent TB requires a special approach. Van der Zalm explains that it is like “a jigsaw puzzle” (Figure 2). You need to review all pieces of the puzzle and, even if not all parts of the puzzle are complete, if the picture is suggestive of TB one should consider treating for TB. It is important to realize that symptoms of children with TB are less typical and that they are at increased risk of developing serious forms of TB after being infected (exposed to individuals with TB), especially TB meningitis and miliary TB, associated with higher mortality. TB diagnostics are challenging and bacteriological confirmation is only achieved in 40-50% of children with TB, the other 50-60% of children are clinically diagnosed. The chest X-ray findings in children with TB are often non-specific and can be difficult to distinguish from those of other respiratory infections or lung diseases.

Van der Zalm goes on to further explain the jigsaw puzzle: TB exposure and infection. Children that are exposed to TB or infected have an increased risk of progressing from primary infection to TB disease. For smaller children, it’s important to realize that they can easily get infected with TB if their caregiver has TB[.5] Many adolescents also develop adult type cavitating disease that can transmit TB, and due to the high number of social contacts made by adolescents, the transmission rate is high.[6] Van der Zalm further stresses that for her, it was important to realise, that if a child is coming from a high burden TB setting and the symptoms suggest TB, you need to think of TB, do investigations, and start treatment, even if the diagnostics may be negative for TB, as only 40-50% of children with TB actually have microbiologically confirmed TB.

Paediatric tb and lung health

After this brief introduction, van der Zalm talks passionately about her field of research: the combination of TB and lung health. It’s a research field that is still developing, and not many studies have been performed in paediatric TB and lung health. Van der Zalm and her research team are looking at the impact of TB and other respiratory diseases on lung health by looking at the long-term outcomes in children diagnosed with TB and children in whom TB was ruled out, and investigating the role of viral co-infections and lung function measurements. In collaboration with the DTTC socio-behavioural science team, they are investigating the impact of respiratory illnesses on quality of life in young children living in South Africa.

There is more and more evidence that paediatric TB can cause long-term lung problems and children can potentially develop chronic respiratory illnesses at a younger age. Van der Zalm hopes that in future she will be able to do intervention studies to evaluate if adjuvant treatment with TB treatment together with immune-modulators can make a difference in long-term lung health outcomes. Here, van der Zalm also refers to her previous experience in research with Cystic Fibrosis (CF). In the field of paediatric TB, there is also much to learn from the holistic approach in children with CF, where, besides the pharmacological treatment, it’s important to pay attention to airway clearance techniques, lifestyle habits (smoking cessation including vaping which is very popular, especially in adolescents), and nutrition.

Dream – vision

When asked whether she has a dream for her field of work, van der Zalm responds that indeed even for an “old and well-known disease such as TB” it’s important to keep dreaming and wishing for a better future. Prevention is key, and still number one. But besides that, she is glad that the DTTC is investing in research to make treatment for TB more child-friendly, for example by reducing the number of pills and the size of the tablets and improving the taste of medicine. On an international level, DTTC works together with a lot of partners. A good example is the Shine Trial [7], which showed that it’s possible to give a shorter TB treatment for non-severe TB in children (reduction from 6 months to 4 months of TB treatment). These results are included in the new International Paediatric TB guidelines issued by the WHO.[8] When it comes to her own field, van der Zalm hopes that lung health will be integrated in TB treatment and TB research. To that end, it’s important to develop easy tools for health workers to focus on the long-term lung effects of TB in children.

Tips and tricks in paediatric tb

Marieke van der Zalm and the author present some general ‘tips and tricks’ about paediatric TB:

- It’s good to realize that the TB burden exists not only in Africa and Asia but also in the eastern part of Europe. With people coming to the Netherlands from different parts of the world (e.g. Ukraine, where the burden of TB disease is higher) it’s good to also consider the possibility of paediatric TB to avoid delay in diagnosis and treatment.[6]

- There is an updated WHO guideline (Sept 2022) on Management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents.[8]

- For health care workers in resource limited settings, also check the WHO operational book on tuberculosis – it’s very useful.[9]

- Check the Diagnostic CXR Atlas for Tuberculosis in Children Image Library, which contains a collection of CXRs from children less than 15 years of age who present with symptoms and signs of TB.[10] It’s a great source for the interpretation of chest x-rays in children with TB.

- As paediatric TB experts, the people from the DTTC are always open to giving advice about clinical cases.[11]

- For complicated paediatric tuberculosis cases, you can also ask advice of the European PTBnet group.[12]

- Every year in September, an International paediatric TB course is organized by the DTTC and Stellenbosch University. Participants come from everywhere in the world. Check the Stellenbosch University website later this year.

- Young doctors with an interest in short-term research on paediatric TB or lung infections may contact Marieke van der Zalm.

References

Pediatric tuberculosis network European trialgroups. [Internet] [Citated 10 April 2022]. (http://www.tb-net.org/index.php/ptbnet). Contact details; ptbnet@googlegroups.com

Unicef. Child Health – Tuberculosis [internet 2019] [citated 5 April 2022] https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/tuberculosis/

Sabine Verkuijl, Moorine Penninah Sekadde, Peter J Dodd et al. Adressing the Data Gaps on Child and Adolescent Tuberculosis. Pathogens 2022 2022 Mar 14;11(3):35 doi: 10.3390/pathogens11030352.

Carvalho AC, Kristki AL. What is the tuberculosis burden among children. 2022. The Lancet. Volume 10, issue 2, E159-160, February 2022. Http://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00548-9

World Health Organization. Pediatric Tuberculosis report 2019. WHO. [Internet] [Citated 5 April 2022]. https://www.who.int/news/item/20-11-2020-overcoming-the-drug-resistant-tb-crisis-in-children-and-adolescents

Annaleise R Howard-Jones, Ben J Marais. Review. Tuberculosis in children: screening, diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020 Jun;32(3):395-404.doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000897.

World Health Organization. WHO Global Tuberculosis report 2020. [internet 2020] [Citated 10 May 2023] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf

Chabala C, Turkova A, Thomason MJ, Wobudeya E, Hissar S, Mave V, et al. Shorter treatment for minimal tuberculosis (TB) in children (SHINE): a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018;19(1):237 (https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2608-5, accessed 23 February 2022)

World Health organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 5: Management of Tuberculosis in children and adolescents. 2022. WHO. [Internet] https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240046764

World Health Organization. WHO Operational book on tuberculosis. Module 5: Management of Tuberculosis in children and adolescents. 2022. WHO. [Internet] https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352523/9789240046832-eng.pdf

Diagnostic CXR Atlas for Tuberculosis in Children – image library. The union. [Internet] [citated 5 April 2022] https://atlaschild.theunion.org

Desmund Tutu Tuberculosis Centre. [Internet] [Citated 5 April 2022] https://blogs.sun.ac.za/dttc/.