Main content

Leave your clinical impressions in the cloakroom

This I learned at the DTM&H (Diploma Tropical Medicine & Hygiene) course in Liverpool. Facts, numbers, statistics are of importance. However, to illustrate what happened to eye diseases in a tropical environment, I will compare my clinical impressions in the seventies in Cameroon, before the AIDS-era, with those in the present time in the same region.

The seventies

In 1970, when I started as a general practitioner in the hospital of Ndoungué in the south-western part of Cameroon, only one ophthalmologist was active in the country. This meant that general tropical doctors had to cope with eye diseases. After a short and intensive period of training at the Rotterdam Eye Hospital and equipped with basic optic instruments, I was able to examine and treat eyes. A growing number of eye patients found their way to Ndoungué, located in a region hyperendemic for onchocerciasis, also called river blindness in cases where eyes are involved. Onchocerciasis is caused by the parasite Onchocerca volvulus, a nematode worm that is spread by the bite of an infected Simulium fly. The fly needs rivers for its life cycle.

In 1976 skin snips were taken at the outer canthus of the eye, to detect the microfilariae (larvae) of the O. volvulus. We found 458 out of 4832 eye patients positive (10.5%) [1]. The density of the microfilariae escaping from the skin snip at the outer canthus of the eye correlates with ocular involvement[2]. Nowadays onchocerciasis in Cameroon is decreasing, due to the annual treatment with ivermectin supported by the African Programme of Onchocerciasis Control (APOC).

In the seventies measles and malnutrition were also serious public health problems in Cameroon. In 1976, 49 children with severe keratomalacia (necrosis of the cornea in measles) were hospitalized in Ndoungué [1]. Due to the successful measles immunization corneal blindness in children is no longer a public health problem. The same is true for malnutrition, in the seventies not a rare finding but thanks to underfive clinics and education it has largely disappeared.

In 1978, after returning to the Netherlands I specialized in ophthalmology. But regular visits to Cameroon and Tanzania, kept me involved in tropical ophthalmology.

Cameroon revisited

During recent visits to the Manna Eye Clinic in Nkongsamba, nearby Ndoungué, I rarely observed ocular signs of onchocerciasis in young people. Skin snips in this clinic are no longer done, due to the risk of HIV transmission.

Nevertheless, I recently saw an 18-year-old man who had optic neuritis in both eyes and many microfilariae in the anterior chambers. He came from a region where annual ivermectin distribution is active. He must have missed his treatment.

On the other hand: In 1978, in Mangamba, a nearby village, nearly all the children between the age of 10-12 years had a kind of ocular onchocerciasis [3]. Now there was a ten-year-old boy from Mangamba who didn’t have any sign of onchocerciasis in skin or eyes: at present this village is involved in onchocerciasis control activities.

Success in onchocerciasis control is obvious, but elderly people with ocular scars in the cornea and retina will still visit eye clinics, also in the regions declared free from O. volvulus transmission.

Nowadays it is remarkable to see the number of patients with intra-ocular inflammation, notably uveitis.

In October 2013 at the Manna Eye Clinic the number of uveitis cases during 8 days were registered, new cases and controls. In this short period 470 eye patients were examined, among them 235 new patients; 29 of the new patients had uveitis; 12 were female, 17 male, age between 20 -75 years. One of the severe uveitis patients, a man of 36, was receiving antiretroviral therapy and could be a case of Immune Recovery Uveitis [4]. The HIV status of other new patients was not known. This observation of 29 new uveitis patients among 235 new patients, 12%, during 8 working days in 2013 may represent an increase compared with the 6% of new patients who had uveitis in the same region in 1976 [1].

Another observation is that in the pre-HIV era of the seventies in Ndoungué examination of the fundus of the eye (retina, choroid and optic nerve) was rarely obscured by opacities in the vitreous. But at present fundus examination in the same region is quite often hindered by dense vitreous opacities caused by vitritis associated with uveitis and possibly also with AIDS and opportunistic infections.

Uveitis underestimated

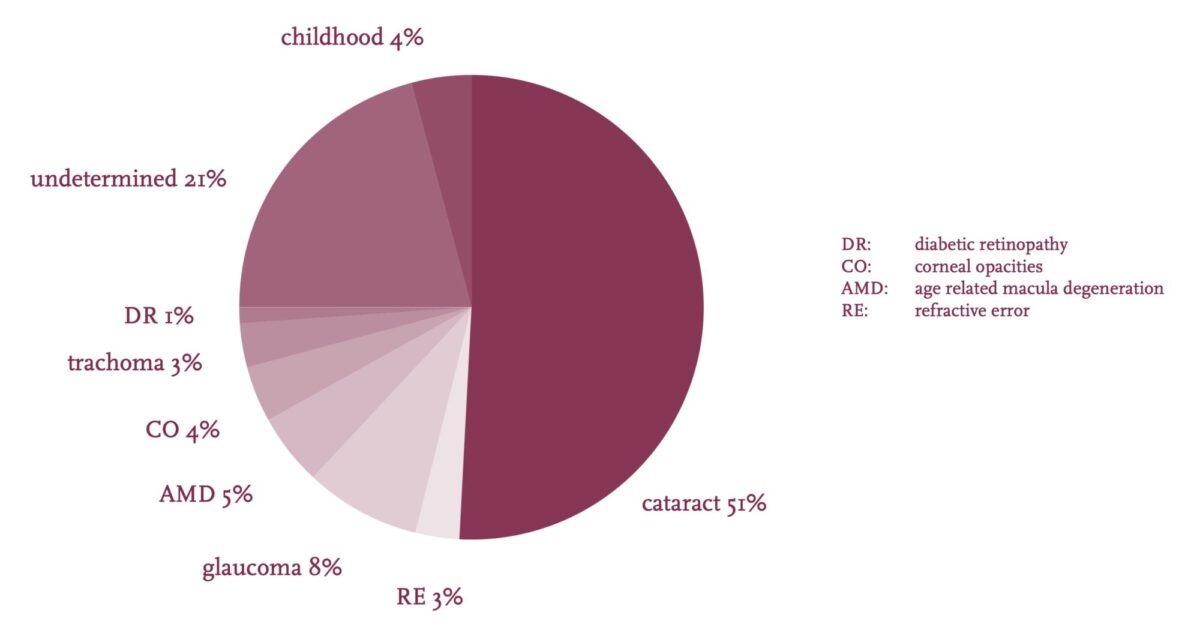

In her thesis ‘Uveitis in Africa’ (1996), Ronday [5] postulates that intraocular inflammation should be added to the list of principal causes leading to blindness on the WHO Eye Examination Record used in blindness surveys. HIV/AIDS, opportunistic eye infections and immune recovery uveitis are not mentioned in blindness surveys in the analysis of causes of vision loss worldwide 1990-2010 by Bourne [6]. They must be hidden in the category “undetermined”: in West, Central and Southern Africa about 35% of the causes of blindness[6].

Source: S.P. Mariotti, WHO

At times in the Manna Eye Clinic a patient, not yet aware of being infected with HIV, asks for medical care because of eye complaints. Equally eye patients are not always open about having AIDS. In a busy clinic a trustworthy person should talk with the patient alone, in a confidential setting, to emphasize the need for HIV testing and for regular medication and controls. In resource-poor circumstances of low-income countries the training of physicians, nurses and laboratory personnel in order to create a multidisciplinary approach of ocular disease in AIDS, will be extremely difficult. A step forward would be the easy availability of a quick and reliable HIV-test adapted to simple circumstances. Moreover it is of great value to increase the awareness and the knowledge of blinding uveitis and possible AIDS involvement in eye pathology among physicians and nurses confronted with eye complaints.

Conclusion

During the last three decades the main causes of blindness as measured in population-based surveys may not have changed due to HIV/AIDS, but the pathology presented to the ophthalmologist in eye clinics in South West Cameroon certainly has.

References

- Koppert HC Ogen in het ziekenhuis van N’Doungué, Kameroen. Ned.T.Geneesk. 1978; 122:1148-9.

- Fuglsang H, Anderson J The concentration of microfilariae in the skin near the eye as a simple measure of the severity of onchocerciasis in a community and as an indicator of danger to the eye. Tropenmed Parasit 1977;28;63-4.

- Koppert HC, Hellemans AC Schoolchildren and ocular onchocerciasis in the rain forest of Cameroon. Documenta Ophthalmologica 1986;61: 211-7.

- Horn GJ van den, Meenken C Ocular disease during HAART-induced immune reconstitution. Tijdschr Infect 2009;4:3-10.

- Ronday MJH et al. Blindness from uveitis in a hospital population in Sierra Leone West Africa. British J of Ophthalmology 1994;78:690-3.

- Bourne RRA et al. A systematic analysis of causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1: 2339-49.