Main content

Doomsday

Friday the 13th is often perceived as a day of disasters, doomsday, a day to be careful and expect the worst. Friday the 13th 1970 definitely can be seen as such. Hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshi fled their homes because of Cyclone Bhola a storm which is still listed as one of the major natural disasters with half a million casualties. Friday the 13th last September was a much more pleasant day. Prof Maarten van Aalst delivered his inaugural speech – Earlier warning, earlier action: resilience in the face of rising risks – in acceptance of the Chair ‘Spatial resilience for Disasters Risk Reduction’ within the Faculty of Geo-information Science and Earth Observation (ITC) at the University of Twente. [1] The flip side of this horrific cyclone in Bangladesh was, according to van Aalst, that we learned a lot and recognised the need for early warning systems. But people are still dying because of hurricanes and storms, though most often the magnitude is much lower. The main idea of this Chair is to operate on the interface of science, policy and practice, and make scientific information useful for actual humanitarian work on the ground, which entails building bridges between academia and practice. As van Aalst explained in our conversation, [2] there is a lot of information at the local level that hardly ever finds its way into the academic world or global decision-making levels such as the Intergovernmental Panels on Climate Change (IPCC). Likewise, good scientific knowledge also doesn’t flow back to local level decision-making and to the ordinary people whom it concerns. Language or cultural barriers and mistrust are interfering factors, and it is in such instances that organizations like the Red Cross often play an intermediary role.

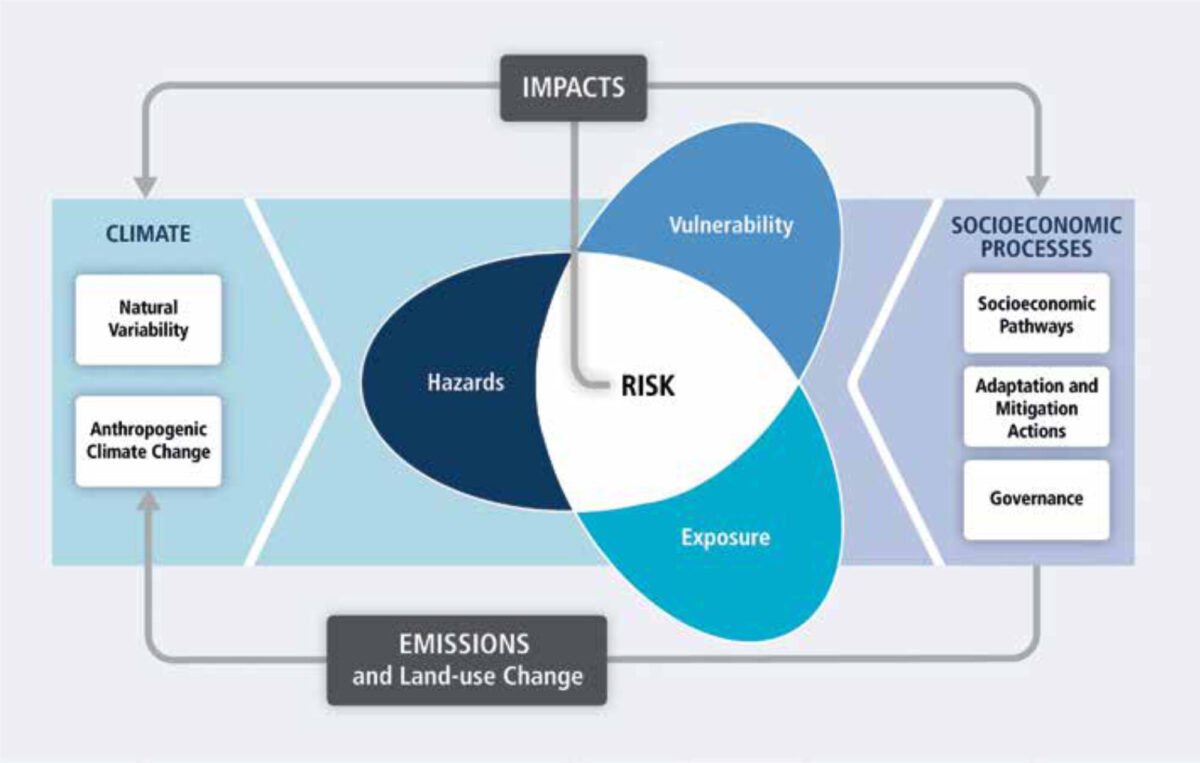

Ref: IPCC, 2014: Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1-32.

Spatial resilience

Resilience can’t be built in isolation from its direct context. As Figure I shows, risk is situated at the centre, although this is not a straightforward top-down relationship. Risk is a convolution of hazards, exposure, and vulnerability that all impact on a person or system. Therefore, risk is influenced by many things. It is also fluid and subject to change – for example as a result of climate change and other factors such as demographic changes, growth in wealth, migration, and urbanisation patterns. Part of our work – hence the title ‘spatial resilience’ – is to better understand this interplay between risk, hazard and resilience, with spatial resilience referring to location and context, including time. [3]

For example, the Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC) works on building resilience in populations and helps respond to disasters. Urban slums are generally most vulnerable when a disaster strikes, for example in case of extreme weather events. When this happens, we act immediately, and we also try to better understand why it happened and trace the antecedents. Slums generally develop in areas that are not ideal for settlement, thereby increasingly putting people at risk. In such cases, besides managing acute situations we document the history and, by doing so, we may be able to anticipate those risks by better understanding the context – in this case the complexity of rainfall forecast, land use, deforestation and so on. Climate change then is one part of the problem, but there are other factors that may aggravate flood risks, such as deforestation upstream. These are the interrelationships that we need to understand better. We also need to make our insights available for humanitarian use, but also for earlier action, longer-term risk reduction, and regular development planning.

Spending wisely

Working on prevention is thought to be a lot more effective and sustainable than just spending more and more on disaster response. We asked van Aalst what kind of preventive measures are likely to have the biggest impact on reducing the disasters caused by climate change. Van Aalst: ‘This is highly context specific, depending on the state of existing risk management and health systems in a country. Take the example of what happened this summer in the Netherlands, and in France. We now see much lower mortality than in the 2003 heat wave in Europe which killed tens of thousands of people. We now have national plans dealing with heat waves, and this has strongly reduced mortality. Yet despite these plans, including for example formal early warning systems and protocols in hospitals and care facilities, the event this summer still resulted in 400 deaths in the Netherlands (1500 in France). This shows that we can still do more in terms of prevention, in which community mobilization in response to early warnings plays a role. We can ensure that information trickles down to the community and that the community knows how to act – in this case for instance by ensuring that vulnerable elderly people in the community drink enough in periods of heat. In other contexts, such as low-lying coastal areas exposed to storm surges, early warning systems that enable people to get out of harm’s way ahead of a disaster can have equal life-and-death results. These are so-called low hanging fruits – where prevention has also proven to have a very good rate of return on economic investment.

The recent report of the Global Commission of Adaptation calculated that investment to alter climate change and adaptation – 1.8 trillion over the coming decade – is estimated to yield benefits of the order of 7 trillion. [4] Investing in warning systems is among the top measures that pay off the most. Other investments include developing smarter cities, better infrastructure, mangrove protection, and making water resources more resilient. However, we need to be sure that warning systems reach the most vulnerable persons in time, that they are as accurate as possible, and that people know what early actions to take. It’s also critical to plan these forecasts and early actions well in advance and to realise that forecasting is a difficult trade. If you wait until a forecast is 100% certain, you are basically too late. However, a false alarm may decrease people’s willingness to respond to future warnings, so we should be clear that there is always a certain risk of a false alarm. It is our task to make people understand these trade-offs. This type of communication with the community is something that requires a lot of attention. It is not always a scientific judgement, but rather a matter where being in tune with the local language and culture becomes crucial.’

Geo-engineering

Is it time to adapt to climate change by accepting that we are not able or willing to cut greenhouse gasses?

Van Aalst: ‘The initial discussions on climate change focused on the magnitude and on whether we actually could reduce greenhouse gasses enough to prevent climate change becoming a real problem. Since about 20 years, we have also been talking about adaptation, accepting that we are not doing enough about greenhouse gasses. We also know that there is no perfect adaptation. For instance, when heatwaves get worse, you can start to adapt in society, investing in urban green spaces and promoting behavioural change etc. But we have to acknowledge that we are not keeping pace with the rising risks, and we already do see impacts – including mortality – of increasing heatwave risks today. In the UN climate convention, this negotiation track is called “loss and damage”.

Looking further ahead, some are already calling for even more drastic options. In the context of the Paris Agreement, countries have agreed we need to keep global temperature rise below 2 degrees, or ideally even 1.5 degrees. It’s a rather abstract number, but the science is very clear that beyond those limits some risks become really difficult to manage. However, we also know that our efforts to reduce emissions are way too slow – we’re currently not on track to keep temperature rise below these limits. And it is possible that at some point there are feedbacks in the climate system that actually lead to a more rapid temperature rise, or that we reach tipping points where the impacts suddenly get much direr very quickly.

This is the sort of situation for which some people are saying we need to be able to quickly cool the climate, for instance through what’s called ‘solar radiation management’ which is basically artificially mimicking volcanic eruptions. In the past, these have indeed led to periods of global cooling, due to large amounts of sulphur dioxide in the upper atmosphere blocking sunlight, directly affecting the radiation balance of the earth, and ultimately cooling down the earth. For instance, in the years after the Mount Pinatubo eruption in 1991, there was a dip in global temperature and even a little dip in global sea level rise. Some suggest that by depositing similar particles into the upper atmosphere with rockets or high-altitude airplanes, we could simply create a similar cooling effect. But there are big questions. First of all, this is not a proven technology. But more importantly, there would also be side effects for instance on rainfall patterns – side effects that we cannot fully predict. And such cooling also does not stop many of the impacts on our oceans, which will continue to get more acidic with rising CO2 concentrations. Perhaps most critically, there will then be really tricky ethical issues. There will be trade-offs with winners and losers from the deployment of such systems – but who would decide about such deployment, and who will compensate the losers? It is likely that a country that is very concerned about some of the impacts of continuous warming will deploy it unilaterally and hurt others. Finally, there is also the risk that these technologies may be seen as an easy way out’ of global warming, and thus take the pressure off the transition to renewable energy. So in all, this is not a magic bullet that will solve all our problems. Instead we need to keep strengthening our ambition to reduce emissions and to deal with the rising risks we will continue to face in the coming decades.’

A race we can win?

Last September, the UN Climate Action Summit took place, convened by UN Secretary General Guterres, with tens of heads of state attending. The summit had the subtitle ‘a race we can win’. We asked van Aalst whether he shared this optimism, and how we can (fast) forward the Paris Agreement on climate change. Van Aalst: ‘We need optimism, but we also need the right level of concern and moreover the right level of scrutiny towards the political declarations being made there. One of the reasons I am relatively positive is the stronger voice of youth movements calling their leaders to account. The fact that we have that public outcry alongside the political grandstanding is critical. First of all, the level of ambition that is committed is important. But secondly, monitor how this translates into practice afterwards, and in practical planning and not just by national climate change ministries and governances but across society as a whole. So we indeed need the scrutiny of many Greta Thunbergs not only in the Climate Action Summit but at all levels, from local communities and cities to national governments and indeed the United Nations.’

Notes

- The Chair was named after Princess Margriet, honorary president of the Netherlands Red Cross, on the occasion of her 75th birthday. Van Aalst is Director of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre (https://www.climatecentre.org) and Coordinating Lead Author at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – the UN organization on evaluating the risks of climate change. He is also a scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, Columbia University, New York, US. Van Aalst studied Astrophysics and Atmospheric Science at Utrecht University and the German Max Planck Institute for chemistry. The focus of his research includes climate change, sustainable development, disaster management and prevention.

- This article is based on van Aalst’ inaugural lecture (see: https://vimeo.com/360553013) and an interview with van Aalst a couple of days after the lecture.

- Spatial resilience focuses on the importance of location, connectivity, and context for resilience, based on the idea that spatial variation in patterns and processes at different scales both impacts and is impacted by local system resilience, in: Cumming Graeme S (2011). Spatial Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems.

- See: https://gca.org/global-commission-on-adaptation/adapt-our-world