Main content

Many patients present at the Emergency Department of hospitals in India with organophosphate (OP) poisoning. While the condition is well known and treatment is available, most patients die or spend a long time in the Intensive Care Unit. Organophosphates are highly toxic nerve agents which act by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, located throughout the central nervous system, causing severe cholinergic toxicity.[1,2] Intoxication can occur after cutaneous exposure, inhalation, or ingestion and causes a variety of symptoms that can progress to paralysis and respiratory arrest.[3] The mortality of OP poisoning is estimated to be between 10 and 20% and is probably higher in India due to lack of access to healthcare.[4] Death usually occurs because of respiratory failure.[2,5]

According to the WHO, unintentional poisoning caused the loss of over 10.7 million years of healthy life (disability adjusted life years, DALYs) and almost 200,000 deaths in 2012, of which 84% in low- and middle-income countries. The estimated number of deaths from deliberate ingestion of pesticides is even higher, about 370,000 per year.[6] As India is one of the countries where organophosphates are easily available, it is estimated to be responsible for a large proportion of the global burden. This article aims to provide an overview of the public health burden of organophosphate poisoning in India.

Results and discussion

The literature makes it clear that OP poisoning can be a public health hazard in three ways, namely acute unintentional poisoning, intentional poisoning, and chronic exposure.

Acute unintentional poisoning

A tragic example of unintentional poisoning occurred in 2013 in the eastern state of Bihar. At least twenty-three Indian school children, aged 4 to 12, died after eating a school lunch contaminated with monocrotophos, an insecticide containing OP. It turned out that cooking oil had been stored in an empty monocrotophos container at the school.[7-9] Although this particular incident made it to the global news, it is not a stand-alone incident.

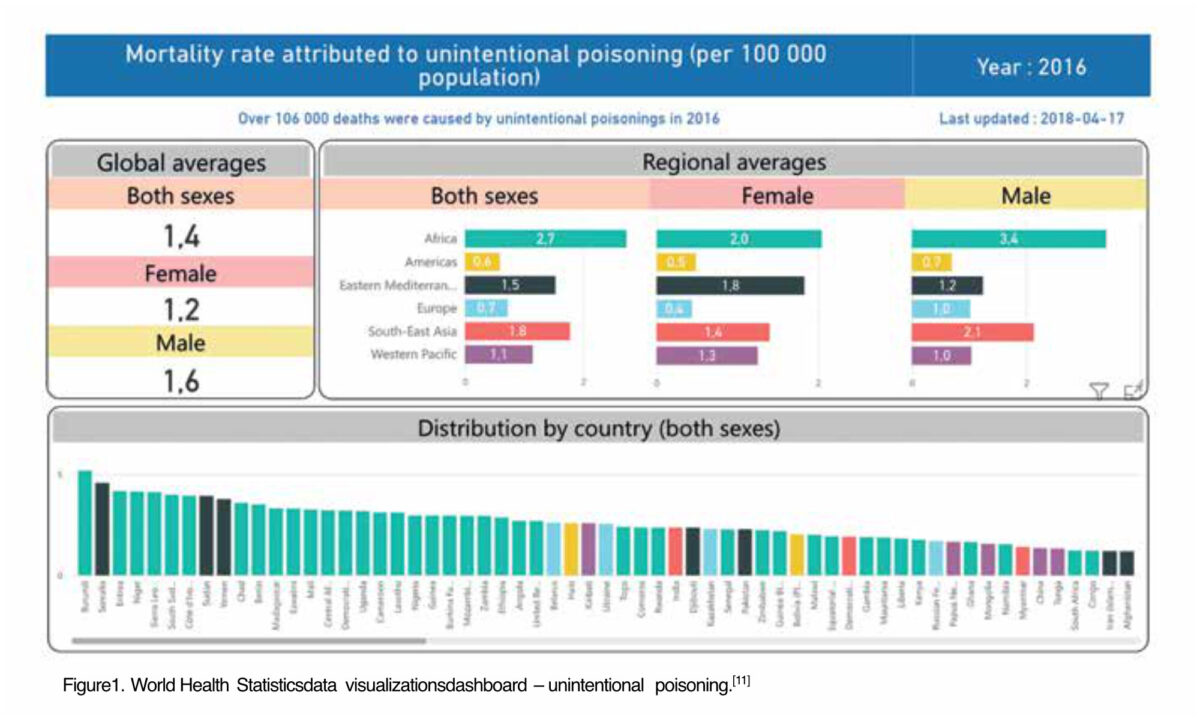

According to the WHO World Bank, the mortality rate attributed to unintentional poisoning in India was 2.4 (male 2.8 vs female 1.9) per 100,000 people in 2016, compared to 5.2 in Burundi (male 6.8 vs female 3.7) and 0.1 (male 0.1 vs female 0.1) in the Netherlands, Switzerland and Singapore.[10] These numbers are not specified by type of poison.

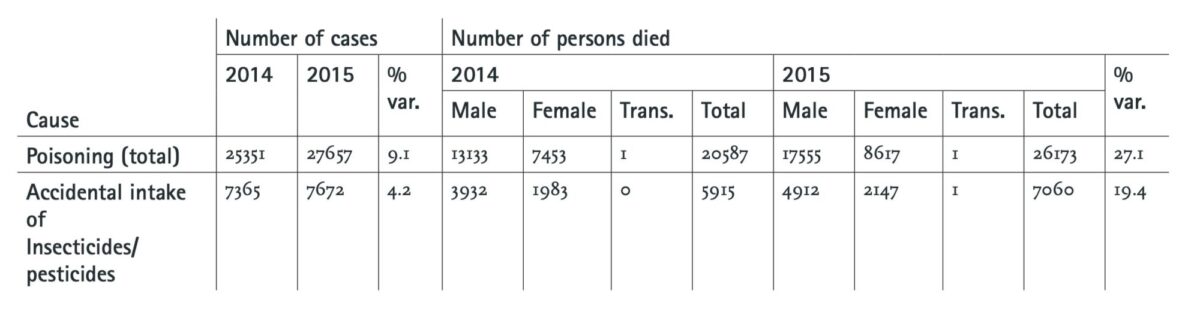

The numbers from the National Accidental Deaths and Suicides Report of the government of India[12] are more specific. For the years 2014 and 2015, the numbers of reported fatalities from accidental pesticide poisonings were 5915 and 7060 respectively.[12] Boedeker et al (2020) conducted a systematic review on the global distribution of unintentional acute pesticide poisoning (UAPP), based on available literature from 2006 – 2018 and supplemented by mortality data from the WHO.[13] They estimated that there are a total of 385 million cases of UAPP per year worldwide, including around 11,000 fatalities. Most of these occur in South Asia.[13] Based on these numbers, the amount of accidental deaths due to UAPP in India would be almost 60% of the total amount globally. As organophosphate pesticides are mainly used in agriculture, it is likely that the most common source of exposure to OP lies within the occupational domain and involves agricultural workers and pest control exterminators. Other exposure could be environmental and would likely occur in the public places and areas close to farms.

Boedeker et al (2020) estimate that, based on a worldwide farming population of approximately 860 million, about 44% of farmers are poisoned by pesticides every year. The same estimate for India resulted in a prevalence ratio of 62%.[13]

Intentional poisoning

As mentioned above, about 370,000 people per year die of intentional OP poisoning worldwide[6]. According to Patel et al (2012), 187,000 people died of suicide in India in 2010, although this is likely an underestimate[14]. The main method of suicide was poisoning, mostly from use of organophosphate pesticides, corresponding to about 92,000 deaths.[14] A sensitivity analysis accounting for underreporting of suicides in India done by Mew et al (2017) resulted in an even higher estimate of 168,000 pesticide self-poisoning deaths annually.[15] This accounts for 19.7% of global suicides and about 45% of total self-inflicted OP poisoning deaths worldwide.[15]

Although the majority of deaths due to suicide in India occurred in men (61% men vs 39% women), Indian women seem to be more vulnerable when compared to international numbers. The age-standardised suicide rate in Indian women aged 15 years or older is more than 2.5 times greater than it is in women of the same age in high-income countries. For men, this was 1.2 times.[14] A Global Burden of Disease study performed between 1990 and 2016 came to the same conclusion.[16] The researchers found that the suicide death rate for Indian woman was 3 times higher than would be expected for geographies with a similar Socio-Demographic Index. The largest portion of suicide deaths in their study was from married woman.[16] The reason for this high suicide rate in women might be due to cultural aspects. Multiple studies from India confirm that domestic violence and gender disadvantage – especially for women in rural areas – are predictors for attempted suicide.[14,17,18] In the Global Burden of Disease study, the authors suggest a correlation with domestic violence, economic dependence, arranged and early marriage, and young motherhood.[16] Furthermore, the lack of treatment for mental illness, especially in rural areas, also contributes the number of suicides.

Homicide by intentional poisoning with OP is not common. This is probably due to the obvious smell and taste and the planning and preparation needed to kill someone compared to shooting or stabbing them. According to a review by Sikary (2018), the prevalence of homicidal poisoning in India varied from 0.03% to 3.7% based on poisoning among other homicidal deaths or other nature of poisoning. Agrochemicals, including organophosphates, accounted for the majority of these cases, but exact numbers were not presented. In almost all of the reviewed cases, the perpetrator was a first degree relative[19].

Chronic exposure

Another factor contributing to the public health burden of OP poisoning that was identified in the literature is chronic exposure to pesticides. While high-level exposure to organophosphates can lead to death in the short term, several studies have suggested that chronic low-level exposure can also have serious health consequences.

A literature review performed by Muñoz-Quezada et al (2016) concluded that evidence suggests an association between chronic exposure to OP pesticides and neuropsychological effects, although there is no consensus about the specific cognitive skills that are affected.[20] Other research suggests an association between exposure to OP and several types of cancer, immunological abnormalities and Parkinson’s disease.[21] However, special concern lies with pregnant woman and unborn babies. There is compelling evidence that prenatal exposure to even low levels of OP is detrimental for the unborn child’s brain development, putting the baby at risk of cognitive and behavioural deficits and neurodevelopment disorders like autism and ADHD.[22]

Children are also more vulnerable than adults. Because their organ systems have not fully developed, they eliminate toxins more slowly from their bodies compared to adults; because their nervous system is still developing, children are believed to be at increased risk for long-term sequelae following organophosphate exposure. However, the long term consequences are not fully understood.[23]

Chronic exposure routes for OP appear to be the same as for unintentional poisoning: occupational and environmental exposure. Evidently, farmers and crop sprayers are at high risk due to their occupation.[21,24] Furthermore, people can be exposed to environmental intake through diet, inhalation, or dermal resorption. [25,26]. Little research exists about how much each path of intake contributes to total exposure to OP. However, people in Punjab were found to use empty containers of pesticides to store food, which also played a role in the mass casualty event at the school in Bihar.[26]

Conclusion

OP poisoning contributes to the burden of disease in three ways: unintentional acute exposure, intentional exposure, and chronic exposure. Each of these have their own specific causes and associated demographics. Unintentional poisoning with OP mostly affects farmers and pest control workers living in rural areas. Intentional poisoning with OP mostly occurs as an impulsive way of committing suicide. Contributing factors to the high suicide rate in India are a combination of social problems and mental health issues, with gender inequality greatly contributing to the number of suicides under women. Women are especially at risk in rural areas, due to their perceived inferiority, poor access to (mental) healthcare, and easy access to pesticides.

The evidence on chronic exposure to organophosphates is not as clear as on the other types of exposure, although multiple routes of exposure have been identified and various adverse health effects described. People working with pesticides, like farmers and crop sprayers, are most at risk for adverse health effects due to cumulative exposure. However, even low concentrations of OP can be dangerous to unborn babies and children.

References

- Bird S, Traub, SJ, Grayzel J. UpToDate. Organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/organophosphate-and-carbamate-poisoning?search=organophosphate%20poisoning&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~22&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Hulse EJ, Haslam JD, Emmett SR et al. Organophosphorus nerve agent poisoning: managing the poisoned patient. British J Anaesthesia, 2019; 123 (4): 457e463 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.04.061.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Nerve Agent and Organophosphate Pesticide Poisoning. Available from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/nerve/tsd.asp

- Acikalin A, Dişel NR, Matyar S, et al. Prognostic factors determining morbidity and mortality in organophosphate poisoning. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33(3):534-539. doi: https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.333.12395

- Sungur M, Güven M. Intensive care management of organophosphate insecticide poisoning. Crit Care. 2001 Aug;5(4):211-5. doi: 10.1186/cc1025. Epub 2001 May 31. PMID: 11511334; PMCID: PMC37406.

- World Health Organization. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Poisoning Prevention and Management. Available from: https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/en/.

- Chander J. Poisoned by the lure of money. The Hindu. September 10th 2013. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/poisoned-by-the-lure-of-money/article5110167.ece

- Reuters. Contaminated school meal kills 25 children. July 17th 2013. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-chidren-poison-idUSBRE96G0AY20130717

- Than K. Organophosphates: A Common But Deadly Pesticide. National Geographic. July 18th 2013. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/130718-organophosphates-pesticides-indian-food-poisoning

- World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/home.

- World Health Statistics data visualizations dashboard – unintentional poisoning. Image from: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.sdg.3-9-viz-3?lang=en

- National Crime Records Bureau. Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India 2015. New Delhi: Government of India; 2016. Available from: https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/adsi-2015-full-report-2015_0.pdf.

- Boedeker W, Watts M, Clausing P, et al. The global distribution of acute unintentional pesticide poisoning: estimations based on a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020; 20, 1875. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09939-0

- Patel V, Ramasundarahettige C, Vijayakumar L, et al. Million Death Study Collaborators. Suicide mortality in India: a nationally representative survey. Lancet 2012; 379(9834):2343-51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60606-0. PMID: 22726517; PMCID: PMC4247159.

- Mew EJ, Padmanathan P, Konradsen F, et al. The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006-15: Systematic review. J Affect Disord 2017 Sep;219:93-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.002. Epub 2017 May 12. PMID: 28535450.

- India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Suicide Collaborators. Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. Lancet Pub Health 2018;3(10):e478-e489. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30138-5. Epub 2018 Sep 12. PMID: 30219340; PMCID: PMC6178873.

- Pillai A, Andrews T, Patel V. Violence, psychological distress and the risk of suicidal behaviour in young people in India. Int J Epidemiol 2009 Apr;38(2):459-69. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn166. Epub 2008 Aug 24. PMID: 18725364.

- Maselko J, Patel V. Why women attempt suicide: the role of mental illness and social disadvantage in a community cohort study in India. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2008;62(9):817-22. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069351. PMID: 18701733.

- Sikary AK, Homicidal Poisoning in India: A Short Review. J Forensic Legal Med 2019 Feb; 61:13–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2018.10.003. PMID: 30390552.

- Muñoz-Quezada MT, Lucero BA, Paz Iglesias V, et al. Chronic exposure to organophosphate (OP) pesticides and neuropsychological functioning in farm workers: a review, Int J Occupational Environmental Health 2016; 22:1: 68-79, doi: 10.1080/10773525.2015.1123848

- Fareed M, Pathak MK, Bihari V, et al. Adverse respiratory health and hematological alterations among agricultural workers occupationally exposed to organophosphate pesticides: a cross-sectional study in North India. PLoS One 2013;8(7):e69755. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069755

- Hertz-Picciotto I, Sass JB, Engel S, et al. Organophosphate exposures during pregnancy and child neurodevelopment: Recommendations for essential policy reforms. PLoS Med 2018 Oct 24;15(10):e1002671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002671. PMID: 30356230; PMCID: PMC6200179.

- Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU). Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences University of Washington. Organophosphate pesticides and child health. 2007. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/opchild/chronic.html

- Dutta S, Bahadur M. Effect of pesticide exposure on the cholinesterase activity of the occupationally exposed tea garden workers of northern part of West Bengal, India. Biomarkers 2019;24(4):317-324. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2018.1556342. Epub 2019 Jan 11. PMID: 30512980.

- Bhanti M, Taneja A. Contamination of vegetables of different seasons with organophosphorous pesticides and related health risk assessment in northern India. Chemosphere 2007;69(1):63-8. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.071. Epub 2007 Jun 12. PMID: 17568651.

- CSE Report; Analysis of Pesticide Residues in blood samples from villages of Punjab. March 2005, CSE/PML/PR-21/2005.