Main content

Even though the global incidence of Tuberculosis (TB) has been declining over the past decades, TB remains a major global health problem.[1] In Paraguay, the national burden of TB is considered ‘intermediate’, with 42 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and approximately 2800 new patients annually.[2] However, in the indigenous populations of Paraguay, which comprises 1.7% of the national population, the TB burden is much higher.[2-4] A recent study performed in the Central region of Paraguay found that the indigenous population had a 66 times higher TB incidence compared to the non-indigenous population of Paraguay.[5] Indigenous populations are considered more vulnerable to the disease due to various factors, including poor living conditions, low education levels, language barriers, cultural beliefs, and distance from their homes to health care centres.[3,6]

Adherence to treatment through DOT

Successful treatment is essential in order to control TB. Adherence to TB treatment, however, is a major challenge in many countries as the currently available treatment is extensive, complex, moderately tolerated, and lengthy.[7] The risk of low treatment adherence increases when patients have a negative treatment experience (e.g. when treatment involves considerable time and money, when side effects to the medication are frequent or substantial or, the opposite, when patients start to feel better and lose their motivation to finish the TB treatment (which may take up to nine months or sometimes more).[8] Low treatment adherence increases the risk of treatment failure and poor outcomes, including disease progression, relapse, development of drug resistance, ongoing transmission, and increased morbidity and mortality.[7,9,10] This highlights the importance of TB treatment adherence and the need for regular and close contact between health worker and TB patients.[8]

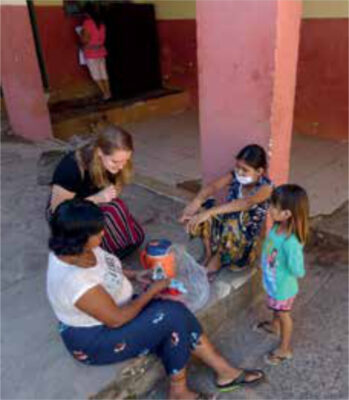

In-person Directly Observed therapy (DOT) was introduced in 2002 in Paraguay to improve treatment adherence. This strategy, recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is considered the gold standard for TB treatment monitoring.[11] DOT consists of a 6-month therapy course together with the provision of information, support, and close supervision of medication intake by a health worker.[11] In Paraguay, free medication and regular visits to the patient’s home are provided by the national TB programme (PNCT), and treatment is monitored by a so-called health promotor, who is often a family or community member.[3]

Despite the introduction of DOT in Paraguay, the treatment success rate was only 70% in 2016, while the international target set by the WHO is 90%.[1,2] This shows that DOT is not as effective as intended in improving treatment adherence and thereby treatment success in Paraguay. In actual fact, DOT is more difficult to apply in low and middle income countries, especially in indigenous populations, as the vast majority of these patients live in resource limited settings far from health care centres.[12,13] DOT visits are logistically complicated (involved both patient and health worker) and resource demanding (requires substantial money, personnel, time, and transportation).[7,9] In addition, DOT can be experienced as inconvenient and disturbing by patients, and issues concerning ethics and privacy have been raised, especially in indigenous populations.[9]

Video observed therapy (VOT)

There is an urgent need for more effective strategies in vulnerable and hard to reach populations. One of the proposed alternatives to overcome the barriers of DOT is Video Observed Therapy (VOT).[7] VOT is a method of treatment monitoring that involves patients recording and submitting daily videos of their TB medication intake using a smartphone.[10] The VOT system (SureAdhere) includes a smartphone application to record, transfer, and store videos of their medication intake, and a website where the uploaded videos in the cloud will be assessed by DOT workers. Also, patients can contact their health care worker in case of side effects, and the DOT workers send them medication reminders on their smartphones to encourage medication intake.[10] Once validated, VOT will replace the specific DOT visits by health workers to monitor treatment adherence, while the routine medication provision and health monitoring visits will remain the standard of care.[10]

VOT has several advantages: it improves patient privacy, it augments patient autonomy, and it is less time consuming. Constant internet connection (which is difficult for patients in remote and hard-to-reach areas) is not required as videos will be uploaded to the central cloud once the patient has an internet connection.[8-10] VOT will enhance patient management efficiency by shifting the focus from treatment monitoring visits alone to increased patient care and real support.[10] Advantages also include the elimination of the need to coordinate DOT visits, improved staff safety, reduced travel time for both patients and health workers, and reduced costs for the national TB programmes and governments.[10]

The effectiveness of VOT has already been studied in various patient settings in the United States, England, Belarus, Kenya, Mexico and Vietnam.[14]. Substantial evidence of reliable treatment monitoring and increased treatment adherence, patient acceptability, and cost effectiveness have been reported.[7-10,12,13] In addition, the most recent study on VOT, a multicentre, analyst-blinded, randomized, controlled superiority trial, performed by Story et al. (2019), demonstrated that VOT was more effective in monitoring Tuberculosis treatment than DOT in a high-risk TB population.[14] It was concluded that VOT might be preferable over DOT for many patients and in different settings, by providing a more acceptable, effective, and cheaper option for TB treatment adherence monitoring.[14] However, up to now, only a few studies have been performed in resource limited settings, and there is not yet enough evidence available of the effectiveness of VOT in socially complex (i.e. indigenous) patient populations.

Pilot study

With our pilot study, we aim to explore the usefulness and effectiveness of VOT on TB treatment adherence in indigenous populations in Paraguay. Participants will be recruited from three Paraguayan healthcare centres: one specialized respiratory hospital, one indigenous hospital, and one regional hospital. Patients are eligible for inclusion if their diagnosis is bacteriologically confirmed and they are drug susceptible, aged ≥ 18 years, and in possession of a smartphone. DOT, which is still the standard of care in Paraguay, will be replaced by VOT in the pilot. All other TB care will remain the same. PNCT will provide medications and monthly check-ups to monitor the health status as usual during their routine visits. During the hospital stay, patients will be adequately instructed on the correct use of the application. After discharge, participants will return home where they will record their medication intake on a daily base during the entire treatment period. Based on the study results, an evaluation will be made to determine whether VOT is suitable as the new standard of care for treatment monitoring in the indigenous populations (in Paraguay).

Conclusion

Despite the efforts made in recent years, TB continues to cause enormous suffering and mortality in Paraguay, especially in indigenous populations.[3] Adherence to TB treatment is still problematic, and new solutions are needed to tackle this problem. Mobile technology plays an increasingly influential role in health care, and mobile phone apps are increasingly being used to improve patient care and treatment outcomes.[8,12] Telemedicine in Paraguay is now considered useful after having been studied for several years. Nationwide telephone and internet coverage reaches 36%.[15] Paraguay has almost 7.5 million active mobile phone lines, which means that there are more active mobile devices than inhabitants.[15] So, as smartphones are increasingly accessible even for the indigenous population in Paraguay, VOT is becoming more feasible and could therefore be a suitable method to improve treatment adherence in the populations where it is currently most needed.

References

- Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- World Health Organisation. Paraguay Tuberculosis Profile 2017. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/sree/Reports?op=Replet&name=%2FWHO_HQ_Reports%2FG2%2FPROD%2FEXT%2FTBCountryProfile&ISO2=PY&LAN=EN&outtype=html

- Guía Nacional para el Manejo de la Tuberculosis. Servicios de Salud locales, distritales, regionales y Unidades de salud de la Familia. Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social. Asunción – Paraguay 2018.

- Barrios A. Plan Estratégico de la respuesta nacional a la tuberculosis en Paraguay 2016-2020. PNCT; 2016.

- Fröberg J, Sequera VG, Tostmann A, Aguirre S, Magis-Escurra C. Assessment of Tuberculosis incidence and treatment success rates of the indigenous Maká community in Paraguay. Article/ Manuscript submitted for publication. 2018.

- Tollefson D, Bloss E, Fanning A, Redd J, Barker K, McCray E. Burden of Tuberculosis in indigenous peoples globally: a systematic review. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2013;17(9):1139-50.

- Holzman SB, Zenilman A, Shah M (editors). Advancing Patient-Centered Care in Tuberculosis Management: A Mixed-Methods Appraisal of Video Directly Observed Therapy. Open forum infectious diseases; 2018: Oxford University Press US.

- Story A, Garfein RS, Hayward A, et al. Monitoring therapy adherence of Tuberculosis patients by using video-enabled electronic devices. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2016;22(3):538.

- Chuck C, Robinson E, Macaraig M, Alexander M, Burzynski J. Enhancing management of Tuberculosis treatment with video directly observed therapy in New York City. Int J Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2016;20(5):588-93.

- Garfein RS, Liu L, Cuevas-Mota J, et al. Tuberculosis Treatment Monitoring by Video Directly Observed Therapy in 5 Health Districts, California, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2018;24(10):1806.

- World Health Organization & Stop TB Initiative. Treatment of Tuberculosis: guidelines: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Garfein RS, Collins K, Muñoz F, et al. Feasibility of Tuberculosis treatment monitoring by video directly observed therapy: a binational pilot study. Int J Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2015;19(9):1057-64.

- Nguyen TA, Pham MT, Nguyen TL, et al. Video directly observed therapy to support adherence with treatment for Tuberculosis in Vietnam: a prospective cohort study. Int J Infectious Diseases 2017;65:85-9.

- Story A, Aldridge RW, Smith CM, et al. Smartphone-enabled video-observed versus directly observed treatment for Tuberculosis: a multicentre, analyst-blinded, randomised, controlled superiority trial. The Lancet 2019;393(10177):1216-24.

- Sequera Buzarquis M. Como es Internet en Paraguay? 2017 [Available from: https://www.tedic.org/como-es-internet-en-paraguay-whyb/].